Development of Modern Macro Economics!

Macroeconomics evolves with the evolution of the economy. Macroeconomic theories change over time. They keep on changing because major economic events — such as the Great Depression of the 1930s the Great Inflation of the 1970s — bring into focus problems within a prevailing theory. Eventually the theory is modified.

Different schools of macroeconomic thought have emerged since the publication of Keynes’ General Theory in 1936. The reason is that there is wide disagreement among economists. There is not much disagreement on theoretical views. But there are often heated debates over the implementation of macroeconomic policy. Economists disagree mainly about the way the theories should be applied to some current problems.

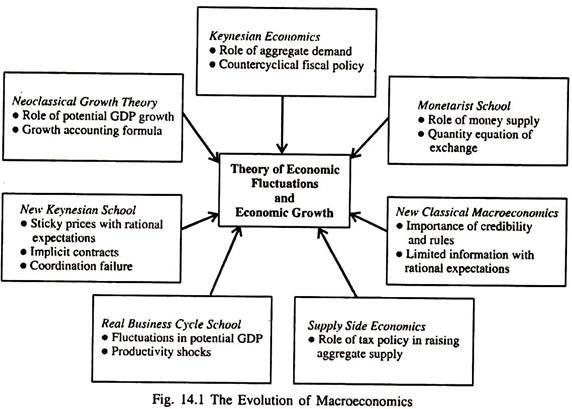

Fig. 14.1 shows the evolution of macroeconomics as a separate discipline. We now make a brief review of the main developments in the area of macroeconomics since the publication of Keynes’ General Theory.

Developments from the 1930s through the 1960s:

As noted in Ch. 1 the publication of J. M. Keynes’ General Theory saw the birth of macroeconomics as a separate discipline. Keynes virtually revolutionised economic thinking. Keynesian revolution refers to a change in macroeconomic thinking, shaped by the Great Depression and the work of Keynes leading to greater considerations of demand-side policies.

From Keynes’ ideas emerged the Keynesian school, a school of macroeconomic thought concerned with pursuing demand-side macroeconomic policies — primarily fiscal policies working through the multiplier — to reduce unemployment and encourage economic growth.

The 1960s saw the emergence of an exactly opposite school of thought, viz., the monetarist school, which holds that changes in money supply are the primary cause of fluctuations in real GDP and the ultimate cause of inflation. Milton Friedman, the leader of the school, restated the Quantity Theory of Money and held the view that “Inflation is always and everywhere a purely monetary phenomenon”.

The monetarists challenged the Keynesian approach to macroeconomics and emphasised the importance of monetary policy in macroeconomic stabilisations.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The monetarist approach postulates that the growth of money supply determines nominal GDP in the short run and prices in the long run. This analysis pins faith on the Quantity

Theory of Money and argues that the velocity of money is stable in which case movements in money supply will affect nominal GDP proportionately.

The Essence of Monetarism:

Three central propositions of monetarism are:

1. The main determinant of nominal GDP growth is the growth of money supply.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Wages and prices are relatively flexible. (Recall that one of the postulates of Keynesian economics is that wages and prices are ‘sticky’.)

3. Private sector is stable. So most fluctuations in nominal GDP result from government action such as change in the central bank’s monetary policy.

The monetarist school argued that monetary policy was a powerful force — indeed, more powerful than fiscal policy. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz showed that decline in money supply growth were responsible for the prolonged duration of the Great Depression.

Developments since the 1970s:

By the mid-1970s— from decades after the start of Keynesian revolution — signs of another dramatic change in macroeconomic thinking began to appear. These changes are referred to as the rational expectations revolution — and they may eventually turn out to be no less dramatic in their impact than the Keynesian revolution. Rational expectations—meaning that people look ahead to the future using all available information — is central to this change in thinking, just as the multiplier or the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) was central to the Keynesian revolution.

The rational expectations hypothesis states “expectations, since they are informed predictions of future events, are essentially the same as the prediction of the relevant economic theory”. At its most basic level the rational expectations hypothesis states that expectations are formed on the basis of all available information relevant to the behaviour of the variable being forecast.

These expectations are formed so as to eliminate systematic sources of forecast error. Thus, the available information is used to generate a forecast that accords with what economic theory would predict from the same information. There should be no predictable, systematic errors in forecasting, although there may be — and almost certainly will be — unpredictable, nonsystematic forecast errors.

The rational expectations revolution started with the appearance of the Phelps-Friedman hypothesis that in the long run there is no trade-off between inflation and unemployment (or the departure of real GDP from potential GDP). Expectations of inflation was the key mechanism that both Phelps and Friedman had used to show why there was no long-run tradeoff only the difference between inflation and expectations of inflation could affect the unemployment rate in the Phelps-Friedman theory.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, a permanent increase in inflation would raise people’s expectations of inflation and thus leave unemployment unchanged in the long run, i.e., at the natural rate. The vertical Phillips curve suggests that any attempt to hold unemployment below its natural rate will result in accelerating inflation. Friedman has provided the most scientific definition of the natural rate of unemployment (NRU).

In his view, NRU is “the level that would be ground out by the Walrasian system of general equilibrium equations provided there is embedded in them the actual structural characteristics of the labour and commodity markets, including market imperfections, stochastic variability in demands and supplies, the cost of gathering information about job vacancies and labour availabilities, the cost of mobility and so on”.

But E. Phelps and M. Friedman were less specific about the short-run trade. To be more specific, economists needed to be more specific about what determined expectations.

The rational expectations assumption itself had a profound effect on macroeconomics. From the rational expectations hypothesis emerged the important idea that reduction of budget deficit might only have a small short-run negative impact. To be more explicit, if people try to anticipate government actions (that is, if they have rational expectations) then when the government announces in advance a programme to reduce the budget deficit, interest rates will fall and tend to offset the short-run negative impact of budget deficit reduction.

Criticisms:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Perhaps the main surviving criticism of rational expectations hypothesis involves the claim that it makes extreme assumptions about the ability of individuals to collect and process information. According to this view, the requirement that the forecasters use the relevant economic theory is too strong, since the average individual in the economy cannot possibly be sophisticated enough to know and use the types of models employed by economists “to study various markets in the economy, and even economists sometimes disagree on the correct model to use in various situations.

John Muth recognised this point in his original work on the subject, where he writes: “the hypothesis… does not assert that the scratch work of entrepreneurs resembles the system of equations in any way”.

New Classical Macroeconomics:

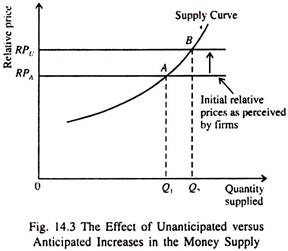

One type of macroeconomic analysis with rational expectations assumes that prices are completely flexible. If this assumption is valid, then changes in monetary policy, if anticipated in advance, have no short-run effect on real GDP or on the economy. This result is known as the policy ineffectiveness proposition and has been stressed by a school of economists called the new classical school. Robert Barro, for example, has argued that only unanticipated changes in monetary policy cause changes in real GDP. This proposition is illustrated in Fig. 14.3.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If the central bank increases the money supply and all prices are perfectly flexible, then all prices will rise. However, if the increase in the money supply is unanticipated and unknown, then firms do not realise that all prices rise. Firms think that only their own prices rise. They wrongly assume that there is an increase in relative price. Hence, they increases quantity supplied from Q1 to Q2.

However, if the increase in money supply is anticipated and known, then firms are not fooled into thinking that there is an increase in relative price. Firms know that all prices have risen. So, they keep quantity supplied at Q1.

In short, the new classical school of macroeconomics holds that prices are perfectly flexible, expectations are rational, and therefore anticipated monetary policy will have no effect on the economy.

The New Keynesian School:

The policy ineffectiveness proposition requires prices to be completely flexible. A second school of thought — which emerged out of the rational expectations revolution — is called the new Keynesian school, which, like the new classical school began in the 1970s. A notable feature of this school is that prices are assumed to be sticky, or slowly adjusting, rather than perfectly flexible. This school of thought assumes prices are sticky and expectations are rational and explain the effect of monetary and fiscal policy on the basis of this assumption.

Sticky Prices:

Thus, unlike the new classical models, anticipated monetary policy affects real GDP in the short run in the new Keynesian models. The efforts of the school have been mainly directed to explaining why prices are sticky.

However, in the opinion of J. B. Taylor: “One of the main contributions of the new Keynesian school has been to provide a way to combine the important aspect of the rational expectations revolution — including the important phenomena of credibility, time inconsistency and policy rules — with a macroeconomic framework that includes the effect of aggregate demand, inflation, monetary policy, and potential GDP growth”.

Coordination Failure:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The new Keynesian school has also emerged with a new hypothesis that the fluctuations in the economy are due to coordination failure. A coordination failure arises in those situations where peoples’ actions depend on what they expect other people will do. If Mr. X is running a firm and expects business to be good, then he will hire more workers and expand production. If he expects business to be bad, then he will not expand production.

Thus, there are two possibilities: people expect bad times and because of these expectations, times turn out to be bad or people expect good times and because of these expectations, times turn out to be good. If people could agree to coordinate their production, then coordination failure, or bad times, might be eliminated. According to new Keynesian economists, periods of deficient aggregate demand might be due to coordination failure.

The Real Business Cycle School:

Another outgrowth of the rational expectations revolution that has increasingly attracted new classical macroeconomists is the real business cycle (RBC) school. It also relies on rational expectations and competitive markets but emphasise different mechanisms to explain short- term economic fluctuations. It consists of a group of economists who believe that shifts in potential GDP — largely due to changes in technology, are the primary cause of economic fluctuations. This school views the fluctuations in real GDP as attributable to fluctuations in potential GDP.

An important contribution of the RBC school has been to focus the attention of macroeconomists more on the supply side of the economy. Clearly, it is not correct to assume that all the fluctuations in real GDP are due to fluctuations of real GDP around potential GDP. The RBC school has provided a method for explaining the other sources of fluctuations in real GDP.

In RBC approach, shocks to investment, technology or labour supply change the potential output of the economy. In other words, they shift a vertical AS curve. These supply shocks are transmitted into actual output by the fluctuations of aggregate supply and are completely independent of aggregate demand.

Similarly, movements in the unemployment rate are the result of movements in the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) due to microeconomic forces such as the intensity of sectoral shocks or to tax and regulatory policies.

Supply-Side Economics:

Supply-side economics is the product of economics that emphasise that reducing marginal tax rates on investments and labour will increase aggregate supply, thereby stimulating the macro-economy. To be more specific, by cutting taxes or reforming the tax system, the growth rate of aggregate supply or potential GDP can be increased.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In principle, there is an affinity between supply-side economics and the RBC school because both emphasise the supply-side of the economy or potential GDP.

The Current State of the Debate:

The new classical macroeconomics still occupies the centre stage of macroeconomic controversies. One key issue in the debate is the extent of price and wage flexibility. Empirical evidence suggests that prices — and particularly wages — move slowly in response to shocks. Moreover, labour markets are never in equilibrium state. When the assumption of perfectly flexible wages is abandoned, stabilisation policy will again assume its importance in affecting the real economy in the short run.

A New Synthesis:

The first decade of the 21st century is witnessing a synthesis of the old and new theories. Economists have come to realise that they must pay careful attention to expectations. In this context, a distinction may be drawn between the adaptive expectation (or backward-looking) approach expectation and the rational expectation (or, forward-looking) approach.

The adaptive assumption holds that people form their expectations simply and mechanically on the basis of past information; the forward-looking or rational approach is based on the assumption that forecasts are unbiased and are based on all available information. For this reason, economists now realise the crucial importance of forward-looking expectations in understanding the behaviour of national economic agents.

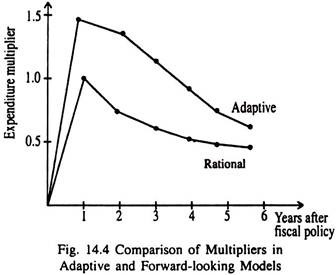

There is one major difference in the expenditure multiplier of models that are adaptive (backward-looking) and rational forward-looking. Since interest rates crowd out investment — and exchange rates affect net exports, adjustment takes place more rapidly in forward-looking models. Forward-looking expenditure multipliers are much smaller than those in adaptive models — as shown in Fig. 14.4.

No doubt new classical approach to macroeconomics has brought many interesting and fruitful insights. What is crucially important is that most economic agents possess information and act intelligently. They react to and often anticipate policy. This implies that their reaction and counter-reaction can change the actual behaviour of the real economy.

The Current Status of Macroeconomic Theory:

At present a consensus between the two major schools of macroeconomics seems to be emerging, viz., the RBC school and the new classical school and the new Keynesian school. That consensus combines the sticky prices and implicit contracts with the careful treatment of information, policy rules, and equilibrium analysis.

The consensus is also evident in the rational expectations models with sticky prices at the domestic and international levels, e.g., at the Reserve Bank of India or the USA’s Federal Reserve Board, the IMF and other institutions with macroeconomic policy responsibility.

In spite of such consensus, the recent history of macroeconomic thought is one of heated debates in which the prevailing view gradually changes over time. Macroeconomic theories evolve as the economies evolve.

So there are different schools of thought, and even those with the same view often disagree on how to implement macroeconomic policy. It is difficult to tell who is right in any particular instance. An economic expert can only make his own judgment in assessing the profitable effects of policies such as tax cut or interest rate hike or exchange rate adjustment.