Some of the essential rules of macroeconomics are as follows:

Rule # 1. Thinking like an Economist:

The social science of economics has its own set of tools — terminology, data and way of thinking. Economists often make use of models to understand and explain macroeconomic phenomena.

Rule # 2. Economic Models:

In macroeconomics we study and examine various facets of the economy such as the influence of national saving on economic growth, the impact of trade unions on the unemployment rate and the effect of inflation on interest rate. The subject is as diverse as the economy.

Economists make use of models to understand the real world — the world around us. Such models are made of symbols and equations and are used to help explain economic variables such as GDP, inflation, and unemployment. Such models may be diagrams, a set of equations or even verbal descriptions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Mathematical models make use of a system of equations in order to explain the relationship among the variables. Such models enable us to reach our conclusions very quickly because they avoid unnecessary (irrelevant) details and focus on important connections more clearly. So they are very useful for macroeconomic analysis.

Various models are used to address these diverse issues. Macroeconomics (like its micro- counterpart) seeks to obtain useful knowledge about an economy mainly through the construction and use of models. These are simplified representations of the real world.

In this title we make use of classical, Keynesian and post-Keynesian models with various modifications — with or without government and foreign trade, rigidity or flexibility of wages and prices, with or without perfect information and foresight, with or without technological change.

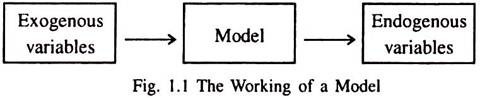

Models make use of two kinds of variables endogenous (dependent) and exogenous (independent). Endogenous variables are those which a model seeks to explain. Exogenous variables are those which a model takes as given and over which economic agents— households and firms—have no control.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A model seeks to show how the exogenous variables affect the endogenous variables. As shown in Fig 1.1, exogenous variables come from outside the model and serve as the model’s input, whereas the endogenous variables are determined inside the model and are the model’s output.

In the IS-LM model, for example, the variable Y (national income) and r (the real rate of interest) are called endogenous variables because their values are determined by the system of equations under consideration. On the other hand M (the money supply) is called an exogenous variable because its value is determined outside the system, i.e., by the central bank.

A model is only as good as its assumptions. However an assumption which is useful for some purposes may be misleading for others. But no single model can answer all macroeconomic questions. In fact, there is no single ‘correct’ model useful for all purposes.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Each of the many different models is useful for throwing light on a different facet of the economy. For this reason macroeconomists present many different models that address different questions and that make different assumptions.

Use of Mathematics:

Since the 1970s, mathematics has emerged as the ‘language of economics’. Many mathematical models are used in macroeconomics. A model provides a structural basis for further studies. A mathematical model reduces the complexity of the real world to manageable proportions.

Rule # 3. Sticky vs Flexible Prices:

Neo-classical economists assumed that prices always adjust to clear a market, i.e., to ensure equilibrium of supply and demand. But in reality we do not find continuous market clearing, i.e., prices do not adjust instantly to changes in supply and demand. Money wages and prices are very slow to adjust. Wage negotiations (contracts) are normally made for two to three years.

Many firms (such as publishers of newspapers and magazines) leave their product prices unchanged for long periods of time — say, for 3 or 4 years. Although the neo-classical market-clearing models assume flexibility of wages and prices, in the real world some wages and prices are found to be sticky.

However, the assumption of price flexibility makes enormous good sense for studying long-run growth in real GDP. But for studying short-run issues, such as year-to-year fluctuations in real GDP and unemployment, this assumption is not much plausible.

In the short run, many prices are arbitrarily fixed. So price stickiness seems to be a reasonable assumption for studying the behaviour of the economy in the short run. In fact, in macroeconomics, the distinction between the short run and the long run is drawn on the basis of price stickiness and price flexibility.

Rule # 4. Microeconomic Thinking and Macroeconomic Models:

Microeconomics studies how households and firms make decisions and how the economic agents interact in the market place. A central principle of macroeconomics is that households and firms seek to optimise. They seek to maximise or minimise something (such as utility or profit or cost) subject to the constraints they face.

Since economy-wide events occur due to constant interactions among the numerous households and many different firms, the two branches of economics — macro and micro — are inseparably linked up with each other. Thus for studying the economy as a whole, it is necessary to consider the decisions of individual economic units.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For example, in order to understand what determines total consumer spending, we have to think about a family deciding how much to consume today and how much to save for the future.

In order to understand what determines total investment spending, we have to think about a firm deciding whether to build a new factory. Since aggregate (macro) variables are simply the sum of the variables describing several individual (micro) decisions, macroeconomic theories are invariably and inevitably based on microeconomic decisions.

The microeconomic-foundation of macroeconomics was laid by E. Phelps, Axel Leijonhufvud, John Muth, R. Lucas, R. Barro, Paul Romer and N. G. Mankiw.

Since the mid-1960s economists such as R. Clower, E. Phelps and others have recognised that the methods used to study the behaviour of consumers, producers, factor-owners and individual markets (microeconomics) can also be used to study the working of the economic system in its totality (macroeconomics).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus they have built the microeconomic foundation of macroeconomics. By using this methodology we adopt a modern approach which treats macroeconomics and microeconomics as different parts of one subject using a unified method of analysis.

Rule # 5. Stock and Flow Variables:

Two types of variables enter into economic relationships and are used in economic models, viz., stock variables and flow variables. A stock variable has no time dimension, but a flow variable is related to time, i.e., expressed as so much per period.

Money is stock, expenditure or transaction in money is a-flow. Wealth is a stock, income is a flow; savings a stock, saving a flow; government debt a stock, government deficit a flow; bank loans outstanding a stock, bank lending a flow.

Price is neither a stock nor a flow variable. It is a ratio between two (actual or potential) flows — a flow of cash and a flow of good. In the ratio the time factor appears both in numerator and denominator and hence cancels out. Liquidity expresses relationship between stocks. It is measured by the percentage of liquid assets to total assets of a person or a firm.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The ratio of saving to income is an example of a flow variable. The velocity of circulation of money or the rate of money turnover is a ratio between a stock and a flow. Since time dimension does not cancel out, velocity must be expressed in terms of a time dimension. Another example of such a ratio is one between a flow of money transactions or income and a stock of money.

Rule # 6. Closed and Open Economies:

In macroeconomics we study the behaviour of two types of economies — closed and open. A closed economy is one which does not have any trading relation with the rest of the world or any link with the world’s financial markets.

An open economy is integrated with the rest of the world. It has trading relations with the rest of the world (through exports and imports) and financial transactions (through inflows and outflows of financial capital).

Rule # 7. Injections and Leakages:

In macroeconomics we study the behaviour of two types of variables — injections and leakages. An injection is any variable or factor which exerts an expansionary effect on national income or output. Examples are investments, government purchases and exports.

On the other hand, any variable which causes national income to fall is called a leakage. Examples are savings, taxes and import. National income of a country remains constant when the sum- total of injections is equal to the sum-total of leakages.

Rule # 8. Desired (Ex-ante and Ex-post) Magnitudes (Values of Variables):

In macroeconomics we study the behaviour of any two types of variables, viz., ex-ante (anticipated or desired or planned) and ex-post (realised or actual). This distinction is very important because various plans of the economic agents, viz., households and business firms, are not always realised or fulfilled.

Rule # 9. Equilibrium, Statics and Dynamics:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A system is said to be in equilibrium when all its significant variables show no change and when there are no pressures or forces for change that will produce subsequent change in the values of significant variables. It is better to say that the forces for change are in balance, rather than that they are absent.

The area of economic analysis that confines its attention to equilibrium positions is static. In his Foundations of Economic Analysis, P. A. Samuelson has opined that the most useful of variety of statics is comparative statics, which compares equilibrium position corresponding to two or more sets of external circumstances.

Static analysis, whether simple or comparative, concentrates only on equilibrium positions. It does not concern itself with the time required to achieve equilibrium position nor with the path by which variables approach their respective equilibrium states. This is one concern of dynamic analysis.

Dynamics is concerned essentially with states of disequilibrium and with change. The disequilibrium may involve the absence of short-run (flow) equilibrium or the conditions or movements of an economy not in long-run (stock plus flow) equilibrium. But the fact remains that the study of movement and change is the province of dynamic analysis.

Equilibrium may be stable or unstable. A stable equilibrium is one that the system’s movements tend to approach or reach. If a stable equilibrium is disturbed, it will be reestablished. This is not so in case of unstable equilibrium.

Rule # 10. Usefulness of the Subject:

Macroeconomics is extremely useful to households, business firms and governments at different levels. The economic well-being of both the poor and wealthy is affected by rates of inflation and interest rate changes. Business firms stand to gain or lose large sums of money when their economic environment changes, irrespective of how efficiently and effectively they manage their functions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Informed and knowledgeable citizens vote in favour of or against governments on the basis of their macroeconomic performance. Macroeconomics is useful to governments in formulating economic policies and avoiding problems that lead to economic collapse such as deep recessions and hyperinflations.

(a) Income and economic growth:

One key variable of macroeconomics is national income. It is used to measure a nation’s economic well-being. The most frequently used measure of a nation’s output and income is its gross domestic product (GDP).

A very exciting issue of macroeconomics is economic growth. Economies grow Tor various reasons. One is population increase since more people can produce more output.

A second reason is increase in factor inputs or the accumulation of the so-called means of production: plant and equipment, roads, communication networks, and other forms of infrastructure make workers more productive. What is more important is the development and harnessing of knowledge to meet economic ends.

An analysis of macroeconomic data reveals that the real output tends to fluctuate around its trend. Sustained ups and downs in economic activities go by the name business cycles. So an important challenge of macroeconomics is to explain the deviations of GDP from its underlying trend: why they occur and persist over a few years and what can be done — if anything to avoid the disruptions that are associated with them.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) Unemployment:

Another important phenomenon associated with business cycles is unemployment, the fact that those who are willing and able to work and looking for jobs do not get them even in a growing economy. The unemployment rate is the ratio of the number of unemployed workers to the total size of the labour force.

The labour force consists of those who are either working or are trying to find jobs. For estimating a country’s labour force we exclude three categories of people from the total population of a country, viz., (i) young people who are not yet working, (ii) the old who have retired, and (iii) those who do not want to work or have given up the idea of working (called discouraged workers), i.e., those who do not search for jobs even.

Unemployment is a social evil. It has negative effects (costs) on society.

Rule # 11. Usefulness of Macroeconomics:

Compared to microeconomics, macroeconomics is closer to our lives. The reason is that it focuses on the economic behaviours and policies that affect consumption and investment, the balance of trade, the internal and external value of the currency, causes and consequences of inflation and unemployment, the determinants of money supply, the central government budget, interest rates and public debt.

In order to study various macroeconomic issues, problems and policies we have to study the interaction among the goods, labour and assets markets of the economy as well as links among national economies that trade with one another, and import and export financial capital.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We often shift our attention from the behaviour of individual economic units such as households and firms, or the determination of prices in particular markets to the market for good as a whole, treating all the markets for different goods — such as the markets for agricultural products, for medical care and legal services — as a single market.

Similarly, we deal with the labour market as a whole and ignore differences between the markets for, say, unskilled labour and skilled labour. We deal with the assets (money and capital) markets as a whole.

This abstraction is necessary because it facilitates increased understanding of the vital interaction among the three main markets of a closed economy — the aggregate goods (commodity) market, the labour market, and the financial (money and capital) market.

Rule # 12. Theme of Macroeconomics:

The discussion of macroeconomics is divided into three parts:

(i) macroeconomic theories,

(ii) macroeconomic problems, and

(iii) macroeconomic policies.

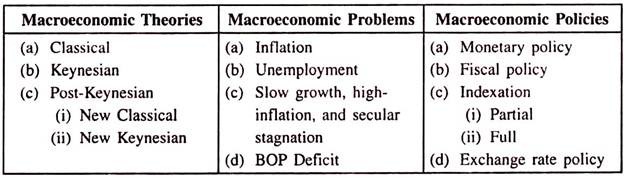

We study classical, Keynesian and post-Keynesian theories. Three main macroeconomic problems are inflation, unemployment, and balance of payments deficit (surplus). Three main policies used to solve the problems are monetary policy, fiscal (budgetary) policy, and exchange rate policy. Table 1.1 summarises the different subject areas (aspects) of macroeconomics.

Table 1.1 Three Areas of Macroeconomics:

In short, macroeconomics deals with such overall economic problems as recession, boom, depression, unemployment, inflation, instability and stagnation. Its variables are national income, GNP, national wealth, aggregate employment, the general level of wage rates, prices and interest rates, and their rates of growth or change.

Rule # 13. Microeconomic Foundation of Macroeconomics:

In recent years the distinction between macroeconomics and microeconomics is becoming blurred. Considerable work in recent years has gone into investigating the ‘microeconomic foundation of macroeconomics’ and much empirical study in macroeconomics has a distinct micro-flavour. R. Lucas and T. Sargent argued that Keynesian macroeconomics is ‘fundamentally flawed’ by its lack of a firm micro-foundation.

And the quest for micro-foundation has been a mainspring of development in macroeconomic theory. Still, the goal of macroeconomics seems to be to understand and predict the behaviour of aggregate economic variables — consumption, investment and employment — rather than to understand a single economic unit or market in isolation. So this difference, in focus, serves as a distinguishing characteristic.

Rule # 14. Two Basic Tools of Macroeconomics: Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand:

Nations do not always grow steadily over time. In the short run market economies are characterised by fluctuations. Such fluctuations are known as business cycles. The pertinent

question here is: how do we assess the performance of nations? Macroeconomic performance of nations can be seen on the basis of aggregate supply-and-aggregate demand analysis.

This enables us to explain the major trends in output and prices.

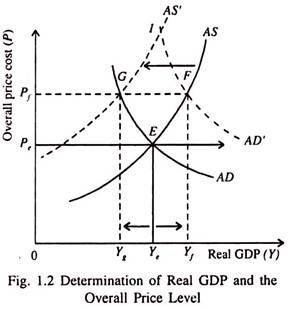

In fact, two important tools of macroeconomics are aggregate supply (AS) and aggregate demand (AD) curves. AS refers to the total quantity of goods and services that a nation’s business firms willingly produce and sell per period.

AS depends on the overall price level as well as the productive capacity of the economy or potential output. Potential output, in term, is determined by the availability of productive inputs (such as land, labour and capital) and the managerial and technical efficiency with which those inputs are combined.

National output and the overall price level are determined by the intersection of the two curves — the AS curves and the AD curve. AD refers to the total amount that different sectors of the economy willingly spend per period. AD is the sum of speeding by consumers, business firms and governments. It depends on the level of prices as well as monetary policy, fiscal policy and other factors.

It also includes net exports (i.e., the difference between exports and imports).

In Fig. 1.2 the AD curve is downward sloping because more of society’s output (GDP) is demanded at lower price. The AS curve is upward sloping because businesses are willing to produce more output at higher price. We see that real GDP (Ye) and the price level (Pe) are determined simultaneously at point E were the AS and AD curves meet.

The resulting output and price level determine the level of employment as also the volume of exports and imports.

Point E shows macroeconomic equilibrium or overall equilibrium of an economy. Such an equilibrium is a combination of the overall price level and quantity at which all buyers and sellers are satisfied with their purchases, sales and prices.

Once this equilibrium is reached, there is no desire on the part of buyers and sellers to change their quantities demanded or supplied and there is no pressure on the price level to rise or fall.

If the AD curve shifts to the right the price level will rise, i.e., there will be inflation in the economy, but output will rise to (Yf). If the AS curve shifts to the left due to, say a rise in the price of crude oil, the same thing will happen to the price level but output will fall this time (to Yg).