The following article will guide you about how to maximize the value of a firm in managerial economics.

Development of Basic Model Firm:

The best way to study and analyse their activities is to develop an economic model of the firm. Such a model will furnish an aid to our study of managerial decision making.

The first and basic model of the firm, which was developed early by economic theorists, assumes that the objective of the owners of the firm is to maximize their short-term gains or profits. Given the firm’s desire to grow and prosper, management is faced with endless questions concerning various issues.

These questions are of a specific nature — whether to add a second shift of workers, whether to raise prices by 4 or 6 per cent; whether to buy new word processing equipment, whether to increase campus recruiting at long distant colleges and management institutes.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But when addressing such issues, decision makers need a standard or criterion by which they can judge whether the outcome of one alternative is better than that of another.

The obvious first choice for a criterion is profit maximization, that is, select the alternative that maximizes profit. But will the purchase of word processing equipment, for example, immediately raise profit? Obviously not. It will have just the opposite effect on short-run profits, as the firm will immediately incur the costs of purchasing the equipment, supplies and needed secretarial training that has to be imparted.

Thus even, if the “ultimate” or long-term objective is to maximize profit, the “immediate” objective is to increase secretarial productivity (that is, increase the number of pages typed per hour worked).

But if the immediate objective is achieved, does it necessarily imply that the ultimate objective is achieved? Again, the answer is no. It all depends on whether the gains in productivity outweigh the increases in cost associated with the purchase of the said equipment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Managerial economics enables business managers to quantify these costs and benefits in light of the ultimate decision criterion. Although profit maximization is the most widely accepted criterion, it is worthwhile to appraise other possible objectives of business firms and to compare and contrast them with the profit motive.

Later, when the emphasis on profit was shifted, or broadened, to encompass uncertainty and the time dimension, the goal of paramount importance to the business firm became wealth maximization rather than maximization of short-run profit.

Practical Difficulties with Profit-Maximization:

However, the profit-maximization goal, as operationally defined, has been criticized on a number of grounds. One significant limitation of the profit maximization hypothesis is its lack of preciseness. In general it provides an ambiguous basis for comparing and ranking alternative courses of action in terms of their contribution to economic efficiency.

The profit-maximization goal fails to define which profits are to be maximized. Should a firm maximize its short-run profits? For example, in the short-run, profits could be maximized by firing all research and development personnel and thereby saving considerable immediate cost.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This decision, however, would undoubtedly have a damaging effect on long-run profitability. Furthermore, there is hardly any agreed upon or understood definition of profits.

Should the firm seek to maximize the amount of profit or the rate of profit? What is the rate of profit? Profit in relation to total capital employed or profit in relation to owners’ equity? Should traditional accounting profits be maximized or, as in the case of property business, should cash flow be the crucial variable to be maximized?

An additional question concerns the difficulty of aggregating and comparing costs and revenues that are realized at different time periods. Most corporate forms of business involve the investment of funds that are expected to generate revenues over an extended period of time.

The profit maximization criterion hardly provides any basis for comparing alternatives that promise varying flows of revenues and expenditures over time.

Another problem associated with practical application of the profit maximization concept is that it provides no sound basis for considering the risk associated with alternative decisions. Two projects generating identical future expected revenues and requiring equal outlays may be vastly different with respect to the degree of uncertainty with which benefits are generated.

The greater the degree of uncertainty associated with benefits, the greater the element of risk associated with the project. An objective criterion for resource allocation within the firm must, of necessity, be able to incorporate this degree of risk into the analysis.

For all these reasons the goal of wealth or value maximization stands today recognized as the primary objective of business enterprise and provides a useful alternative objective to guide resource allocation decisions in the firm.

Limitations of the Theory of the Firm:

In recent years the profit or wealth maximization hypothesis has been challenged by a number of critics. They feel that the managers of firms are not interested in profits alone. They also try to pursue certain non-monetary aspects such as power, prestige, leisure, status, employee welfare and welfare of the society at large.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Furthermore, H.A. Simon has hypothesized that managers do not really seek to maximize instead they try to satisfied, i.e., they tend to be satisfied with a reasonable (target) rate, of return on investment which is consistent with the long-term survival of the firms to which they belong.

They do not seek to maximize profit but to derive a return on capital employed so as to pay satisfactory dividend and thus oblige the shareholders.

It is extremely difficult to determine whether the management is trying to maximize firm value or whether it is merely attempting to satisfy its shareholders while pursuing other goals.

In fact whether a community activity undertaken by a firm leads to long-run value maximization is debatable. It is also questionable whether high salaries and substantial perquisites are really necessary to attract and retain managers who can keep the firm ahead of its rival producers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When a risky venture is rejected, it is difficult say whether this reflects conservatism or inefficient risk avoidance on the part of management, or whether it, in fact, reflects an appropriate decision from the standpoint of value maximization, given the risks of the venture compared with its potential return?

It is very difficult, if not impossible to give accurate answers to such questions and this has led to the development of various alternative theories of firm behaviour.

Some of the more prominent alternatives are models in which size or growth maximization is assumed to be the primary objective of management, managers are assumed to be most concerned with their own gain (utility) or welfare maximization, and the firm is treated as a collection of individuals with diverse goals, rather than a single identifiable economic unit.

Each of these theories, or models, of managerial behaviour has added to our stock of knowledge and understanding of business behaviour. Still, none can totally replace the basic micro-economic model of the firm as a basis for analysing decisions. It is worthwhile to examine the underlying cause in detail.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The neoclassical theory of the firm, as it has evolved so far, postulates that managers seek to -maximize the value of the firm, subject to various constraints imposed by resource limitations, technology and society.

The theory fails to explicitly recognize other goals, including the possibility that managers might take actions that would benefit someone other than shareholders perhaps the managers themselves or society at large but would reduce shareholders’ wealth.

Thus, the model deliberately ignores the possibilities of satisfying, managerial self-dealing and voluntary social responsibility on the part of business or its management.

Having accepted that firms assert the existence of multiple goals, engage in active “social responsibility” programmes and sometimes exhibit what Nobel. Laureate H.A. Simon calls ‘satisficing’ behaviour, is the economic model of the firm really adequate as a basis for any study of managerial decision making?

Firstly, it is often felt that the intense competition both in commodity markets, where firms sell their output and in the capital market, where they acquire the long-term finance necessary to engage in productive enterprise, forces management to seek value maximization in their decisions.

Shareholders are of course interested in value maximization since it affects their rates of return on ordinary shares. Managers who pursue their own interests instead of those of shareholders run the risk of losing their jobs. Takeover pressure from strong rivals (“raiders”) has been significant in the USA during recent years.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Sudden takeovers are especially harsh to inefficient managers who are usually fired. Furthermore, a number of managerial compensation theories indicate a strong positive correlation between firm profits and managers’ salaries. Thus, managers are to have a strong economic incentive to pursue value maximization through their decisions.

Secondly, there is need for cost-benefit analysis of arty action before a reasonable decision can be arrived at. This applies to a decision to satisfice rather than to maximize.

Before a firm can decide on a satisfactory level of performance, management must examine the costs of such an action. Would it be wise or profitable to seek out the best technical solution to a problem if the costs of finding this solution greatly exceed resulting benefits? Obviously not.

Indeed, what apparently seems to be satisfying on the part of management ultimately turns out to be profit or value maximizing behaviour, once the costs of information gathering are taken into consideration.

Likewise, short-run growth maximization strategies can often be seen as consistent with long-run value maximization when production, distribution or promotional advantages of large firm size are best understood and appreciated.

In short, without a clear understanding of the full costs and benefits associated with individual managerial decisions, along with a consideration of short and long-run implications of such decisions, it becomes hazardous to reject the value maximization hypothesis.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally, the value maximization model provides a clear insight into a firm’s voluntary social responsibility activities, though initially the model ignored this possibility. The neoclassical theory of the firm emphasizes profits and value maximization while ignoring the social responsibility of business.

Multiple Business Goals:

As soon as we depart from the simple economic world of short-run profit maximization in which business decisions made this month are expected to affect only revenue and cost in this month and turn to a world in which today’s decisions have uncertain effects on revenue and cost for many years to come, the goal of profit maximization seems to offer an inadequate explanation of a firm’s behaviour.

In fact, various alternative formulations of the objectives of the firm have been set forth:

1. Wealth maximization theories in which the firm attempts to maximize the present value of its future profits.

2. Sales maximization theories in which the firm seeks to maximize sales subject to a minimum profit constraint.

3. ‘Satisficing’ theories in which the firm tries to achieve satisfactory performance for multiple targets such as a target market share, a target profit and satisfactory service to customers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. Growth maximization theories in which the firm tries to maximize the growth rate of a target such as market share or sales turnover.

5. Prestige and service maximization theories for non-profit or regulated businesses in which the firm attempts to maximize the service provided and prestige earned, given its budget constraint.

The wealth maximization model is based ©n the assumption that the primary goal of business is to maximize the wealth of its owners by maximizing the present value of long-run profits.

The model provides a decision making criterion that leads the decision maker to:

(1) Quantify or numerically measure the future annual costs and benefits of each decision alternative,

(2) Estimate the resulting annual profit of each alternative and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(3) Choose the alternative whose future annual flow of profits has the greatest value when discounted back to the current time period (using the current market rate of interest that reflects the time value of money).

Critics have often argued that this model of long- run profit maximization is too narrow and incapable of describing all the non-economic, i.e., the legal, moral and social constraints placed on decision makers.

Models of constrained sales maximization and models of satisficing are presented to highlight the point that business goals are not only multiple but also conflicting in nature.

These goals or objectives are:

(1) Maximization of profits,

(2) Maximization of sales,

(3) Maximization of market share,

(4) Maximization of customer services,

(5) Maximization of worker satisfaction, and

(6) Maximization of the firm’s social responsiveness and so on.

W. J. Baumol first suggested a model in which firms maximized sales subject to a profit constraint, the constraint that they reach a minimum acceptable level of profit in the short-run. In this model, profits must be sufficient to satisfy shareholders and to prevent takeover or external control over the firm, for reorganizing it.

R. M. Cyert and J. E. March set forth a model of satisficing by arguing that the firm attempts to achieve multiple goals of which one is profit. In essence, managers in this model are literally pursuing multiple goals and are content to achieve satisfactory (not maximum) levels of multiple targets.

As the firm gradually becomes more and more efficient in achieving multiple targets, R. H. Day has argued that the satisficing strategy approaches the goal of long-term wealth maximization.

For example, if a firm were efficient enough to estimate accurately the goodwill obtained from giving money to local charities, it could be both a generous benefactor and a wise profit maximize.

In an imperfectly competitive world, individual managers make companies donate generously to “good causes” for both humanitarian and selfish (profit- oriented) reasons, but they are unlikely to be certain about the net effects of these donations on the city or on the firm.

Baumol and Robin Morris have also presented growth maximization theories. Essentially, these are models of profit maximization achieved by growth of sales turnover.

That is, as opposed to static short-run models which show a firm reaching an equilibrium output and maintaining this level of sales, models of growth maximization focus on how rapidly a firm’s sales should grow in order to achieve the greatest percentage growth rate in profits.

Thus these models are not fundamentally different from the wealth maximization models inasmuch they view the world of business decision making as a dynamic, time-oriented process.

Prestige and service maximization theories are also variants of behavioural models. They show how managers in the non profit seeking organization perform, or how middle-level bureaucrats in large corporate organizations behave.

As applied to non-profit seeking organizations such as (hospitals, charitable trusts, universities, and governments) the model predicts that managers will, subject to the constraints of their operating budget, seek to maximize both services provided to the public (for example, low-cost education for adults, or “free” government brochures on housing facilities for the middle-income group) and the prestige of the organization (hiring a Nobel Laureate scientist or buying the latest medical equipment).

When applied to the business environment, this model appears to be an extension of the satisficing theory because it provides two additional goals — service and prestige — for the decision maker to balance off against profit and market share.

The wealth maximization model has, of necessity, to abstract from reality if it is to be manageable and provide a basis of predictions of firms’ behaviour. Even though it ignores other variables such as “service” and “prestige”, the issue is whether this model provides better predictions than alternative theories.

Throughout the title we shall assume that the wealth maximization model best describes the behaviour of firms in the real commercial world. This does not necessarily imply that firms try to squeeze every last drop of profit o’ of their operations, but that profit is the primary goal, with a host of subsidiary goals that operate to constrain unbridled profit maximization by the firm.

The traditional profit-maximization hypothesis has provided a wide range of valuable insights into the efficient allocation of scarce resources within the enterprise.

Notwithstanding these successes, the shortcomings of the model (such as the failure to incorporate the time dimension in the decision process as also the failure to deal explicitly with risk and uncertainty associated with decision making process) led to the development of a more comprehensive and refined model.

The shareholder wealth-maximization (or value-maximization) model, assumes that the objective of the firm is to maximize the value of the firm as measured in the market place, i.e., maximize the market value of the firm’s share.

Definition of Value:

Since the basis of the latest model of firm behaviour is maximization of the value of the firm, it is necessary at the outset to clarify the meaning of the term ‘value’. In fact, various alternative definitions of the firm have been suggested by economists and financial analysts alike — book value, market’ value, liquidating value, going-concern value, and so on.

Prima facie, value can be defined as the present value of the expected future cash flows of the firm. Cash flows are often equated with profits. Therefore the value of the firm today, known as present value in the literature of financial management, is the value of its expected future profits, discounted back to -the present by an appropriate rate of interest.

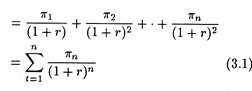

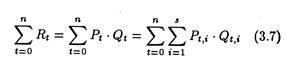

The essence of the model, with which we will be concerned throughout the text, may be presented as follows:

Value of the firm = The Net Present Value (NVP) of Expected Future Profits

Here π1π2………….πn represent the expected profits

in each year, t; r is the appropriate rate of interest which acts as the discount factor.

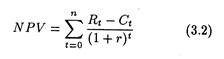

Since profits equal to total sales revenue (R) minus cost (C), equation (3.1) may be alternatively expressed as

Where Rt stands for revenue from selling Q units in period t,

Ct stands for cost of producing Q units in period t,

r stands for interest rate or discount factor, and

t stands for time period (t equals zero in the current time period and n at the end of n periods).

The numerator Rt—Ct of the ratio in Equation (3.2) measures net income in each period; the denominator contains a compounding interest rate fetor (1+r)t which is used to transform or discount future rupees into present rupees.

For example, if projected revenue (R) in year 5 (n = 5) equals Rs. 1000, projected cost (C) equals Rs. 700, and the interest rate (r) is 10%, then projected net income in year 5 is Rs. 300 (Rs. 1000 – Rs. 700), but the net present value is Rs. 186.28 [Rs. 300 + (1.10)5], Equation (3.2) calculates the NPV of the firm’s income stream by carrying out this discounting process for each time period and then summing the result for all w time periods.

The wealth maximization model is based on the assumption, therefore, that the effects of business decisions can be quantified in terms of future revenue and cost. When faced with decision alternatives, the firm can select the option that maximizes its wealth — that is, the net present value of its future profit flows.

The more difficult it is to quantify the results of an action (say, of a new advertising campaign) the less use can be made of Eq. (3.2). But the basic rationale of profit-maximizing behaviour remains unchanged.

Firms that successfully generate more output values from less input values by producing goods and services desired by consumers are engaged in (positive) value creation process, and Eq. (3.2) merely quantifies the basic process. When a firm creates more and more output values from less and less input values, it is said to be economically viable.

Our goal is to expand this model so that it becomes clearer how the activities of each unit in the organization effect the overall value creation process and how these activities bear relevance in any study of managerial economics. At the outset, we have to clarify the meaning of ‘value creation’ by the firm.

Value Creation and Profit:

Suppose the Oxford Book & Stationery Co. produces and sells certain novelty items along with books and that the marketing manager has come up with a new idea for a product.

The company will buy small cardboard boxes, place a shiny rock in each box, put a ribbon on the box, and sell the product as a “pet rock”. This new novelty product will cost approximately Rs. 2.00 to produce, and the firm will market it at a price of Rs. 5.50. If the product turns out to be successful, the firm is said to have created economic value.

A firm creates value, therefore, when it can sell its product for a price that exceeds the economic value of the resources (land, labour and capital) that were consumed in its production.

If consumers were willing to pay only Rs. 1.50 for a pet rock whose resource cost was Rs. 2.00. the product would be unprofitable, resources would have been wasted and the firm would stop production of the item with a view to minimizing its losses.

In general, for a market-oriented economy, one can suggest that when profit-seeking business firms are making profit, they are simultaneously fulfilling society’s goal of value creation and the firm’s objective of economic survival.

In a free market, it is impossible to earn a profit unless the firm is economically viable, i.e., creating economic value. In terms of Eq. (3.2) the firm undertakes actions designed to maximize its wealth by maximizing the net present value (NPV) of its future income stream.

If we assume that its costs (C) truly reflect the social opportunity cost of resources, i.e., total resource costs to society, and assume a competitive free market environment, then the firm’s goal of maximizing the NPV will be consistent with society’s desire to extract the maximum possible economic value from its scarce resources.

Value Creation and Dividend:

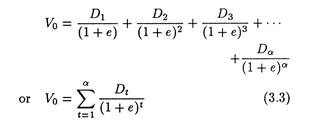

The value of a firm’s shares or stocks is equal to the discounted (or present) value of all future cash returns expected to be generated by the firm for the benefit of its owners. The shareholders of a company generally receive a portion of the income earned in each period.

The portion of the income earned and distributed to the ordinary shareholders is called dividends. Hence the value of a firm’s stock is equal to the present value of all expected future dividends (or other distributions, such as the proceeds from the sale of share by an individual investor), discounted at the shareholders’ required rate of return or

where V0 is the current (present) value of a share or stock, D represents the dividends expected in each of the future periods (1 through∝ ), and e equals the investors’ required rate of return.

For the purposes of analysis here, it is only necessary to recognize that Re. 1 received one year from now is generally worth less than Re. 1 received today, because Re. 1 today can be invested at some rate of interest, for example, 10%, to yield Rs. 1.10 at the end of one year.

Thus an investor who requires (or has an opportunity to earn) a 10% annual rate of return on an investment would place a current value of Re. 1 on Rs. 1.10 expected to be received in an accounting year.

Equation (3.3) has a number of useful and interesting features. Firstly, one is to explicitly consider how cash flow is generated over time. By discounting all future dividends by the required rate of return, e, equation (3.3) recognizes the fact that a rupee received in the future is worth less than a rupee received today.

Secondly, Equation (3.3) provides a conceptual basis for evaluating differential levels of risk. For example, if a series of future cash flows is highly uncertain (i.e., likely to diverge substantially from their expected values), the discount rate, e, can be increased to account for this risk. Hence the wealth-maximization model of the firm removes the two primary defects of the profit- maximization model.

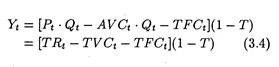

Equation (3.3) has a common thread that runs through the entire title. As noted above, Dt represents the portion of each period’s after tax net income, yt, that is distributed among the firm’s shareholders. Income in any period may be defined as

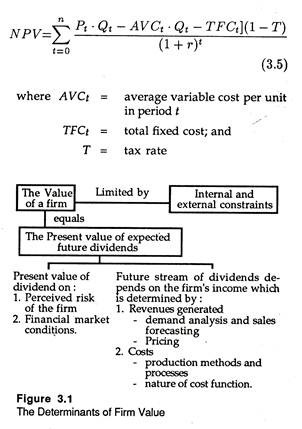

where Pt is the price per unit of output sold in period t, Qt is the quantity of output sold in period t, TRt = Pt Qt, AVCt is average variable cost in period f, AVCt. Qt = TVCt is total variable cost, TFCt is total fixed cost in period t and T is the firm’s tax rate.

The first term on the right-hand side of Equation (3.4) represents the total sales revenue generated by the firm. From a decision making point of view, this value is dependent upon the nature of the firm’s demand (average revenue) function and the firm’s pricing decisions. [These two aspects will be discussed separately].

In addition, the allocation of a firm’s investment expenditure over time or the choice of investments made by the firm in the long run, i.e., the capital budgeting decisions — determines what proportion of total cost will be fixed and what portion will be variable.

A firm which chooses a capital-intensive technique of production is normally supposed to have a higher proportion of its total costs of operation represented as fixed costs than will a firm that chooses a more labour-intensive technique.

The discount rate e, which investors use to value the stream of income generated by a firm, is determined by the perceived risk of the firm and by the financial market conditions including the level of expected inflation.

In arriving at its pricing, output, production and cost decisions, management is faced with numerous legal, behavioural, value-based, and environmental constraints on its actions. These constraints will be brought into focus in the concluding part of the title.

The integrative nature of the wealth- maximization model is spelt out in Figure 3.1.

Understanding the NPV Model:

As are all models, Eq. (3.2) is a highly simplified version of business (firm) behaviour. To make it more purposive the equation may be disaggregated and the individual pieces may be looked at in greater detail. By rewriting Eq. (3.2) in terms of its subcomponents, we can get a more detailed model that provides an economic perspective on a wide variety of topics concerning the day to day operation of a business firm.

Value Creation and Responsibility sharing:

Needless to say, value creation is a composite art and every department in the area of functional management has a contribution to make to fulfil the overall objective of the firm, viz., maximization of its NPV. So responsibility has to be shared.

For instance, the marketing department has a major responsibility for sales; the production department has a crucial responsibility for costs; and the finance department has a strategic responsibility for the discount factor in the denominator.

However, these responsibilities in the basic functional areas of the business often do overlap. The marketing department, for instance, can achieve cost reduction for a given order size and timing. Likewise the production department can raise the levels of sales (turnover) by improving the quality of products and making new products available to the sales people.

Furthermore, various other departments within the business enterprise — for example, accounting and finance, personnel, transportation and communication, engineering etc., — provide information or services of vital importance for achieving cost control and raising market share (i.e., output expansion).

Thus it is clear that it is possible to make an overall evaluation of the various decisions in different departments of an enterprise in terms of their effects on the value of the firm as expressed in terms of equations (3.1) and (3.2). These points may now be discussed in detail.

Marketing and Sales — Demand Theory:

The term Pt, Qt, in Eq. (3.4) or Eq. (3.5) measures total sales revenue (Rt) in time period t. While describing the firm’s revenue flows we consider the revenue this year (R0), next year (R1), five years hence (R5), and n years in the future (Rn).

A company’s time horizon depends on the numerical value of n — that is, how many years does the company need to go into the future? The marketing and sales departments have, of necessity, to be concerned about the price and quantity of the product sold this year (P0. Q0) and n year in the future (Pn. Qn).

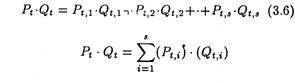

In theory we assume that a firm produces only one product. But in practice we observe that most firms are multi-product firms, i.e., they produce many products, not just one.

We can express this relationship for s different products as follows:

Thus the sum-total of the income stream for n periods, may be expressed as

But what does this imply from the perspective of the marketing and sales departments? First we are saying that at any point in time, there are s products (Qt1 Qt,2……. Qt, s) and s prices (Pt1, Pt 2, Pts,).

The firm is a pure competitor and is so small a part of the market that it has no economic power (say, a typical wheat or jute farmer who plants wheat and/or jute), product price is determined by the impersonal forces of supply and demand.

Thus price adjustment by a single firm is not possible and the sole marketing and sales decision is how much to produce (or, in the case of a farmer, how much to plant of various crops), i.e., an individual firm can only make quantity adjustment. For an oligopolistic producer (one of a few dominant car-producers), decisions have to be made as to

1. How much money should it spend to advertise and promote each product?

2. What price should it charge for each product?

3. How much of each car it is likely to sell?

4. Should it introduce a new car model?

Finally, at the other extreme from competition, are the marketing and sales departments of a monopolist, who is not bothered about competitors since it has none, but needs to be concerned about potential competition, international competition, trade union pressure for higher wages and better working conditions and possibility of rapid technological change in the industry.

Behind all of these questions lies are issue of product demand. Irrespective of how much power a firm has, it needs to understand the determinants of demand for its products. What we have simply denoted as Pt. To assist the firm in the process of value creation, the marketing and sales departments have to understand both demand theory and statistical demand analysis as also other demand estimation techniques. Demand theory particular (analysis) seeks to search out or identify the major factors affecting the market demand for a commodity.

For example, the demand for a small item like ball point pen depends on various factors price, price of substitutes such as pencils, income of buyers, product design, production quality and durability and so forth.

To create value, firms must first discern what consumers are actually willing to buy and ready to pay for. That is, the marketing and sales departments can only create value if they succeed in identifying or analysing the proximate determinants of consumer demand properly.

A company’s marketing time horizon is, in turn, extended far or near, depending on the nature of the product and the fluctuation of consumer demand. Some products (novelty items, such as a pet rock) may evolve slowly over a number of years.

For every variable that may affect consumer demand, there are marketing and sales specialists whose task is to monitor the performance of the major demand determinants.

While the sales staff at a chain store, selling packed food like fried chicken, monitors closely sales volume (Qt) and revenue (Pt. Qt), there are a host of factors other than price that affect demand — quality of product, service, location, convenience, advertising and direct actions by its competitors.

Accounting and Cost Theory:

The symbolic expression of total cost (C) in Eq. (3.2) was replaced by the variable cost (AVCt, Qt) and fixed cost (TFCt) components in Eq. (3.5)

Ct = AVCt Qt + TFC1(3.8)

or Ct = TVCt + TFCt (3.9)

Like the time horizon for revenue (R), we can also speak of the time horizon of costs, i.e., the yearly pattern or series of observations for variable cost this year (TVC1) and five years in the future (TVC5). By analyzing Eq. (3.5), it becomes clear that the greater the difference between sales revenue (Rt) and cost (Ct), the larger the amount of economic value created by the firm.

The marketing and sales departments carry out their responsibilities by implementing policies that will raise turnover or total sales revenue and physical volume (Q) for current and future years.

Value creation is not a one-sided or one- dimensional activity involving increase in sales revenue. Every act of choice in the business world has a unique set of costs and benefits, and from traditional microeconomics the following decision rule may now be developed:

If the extra or marginal revenue (MR) resulting from the production and sales of an extra unit of output exceeds the extra or marginal cost (MC) of doing so, then the decision maker has increased his (her) profit and should therefore expand output further.

Here MR = ∆TR/∆Q; MR measures extra revenue (∆TR) divided by change in output (∆Q)

MC = ∆C/∆Q; MC measures extra cost (∆C) divided by ∆Q.

It may be noted that every business decision is taken at the margin. The value creation process is no exception to this rule. It is also based on decisions made at the “margin”, that is, businesses are constantly striving to improve their profitability or financial performance by assessing the incremental (marginal) effects of a decision on revenue and cost.

Just as there are two sides of a market (supply and demand), there are two sides of every decision (marginal cost and marginal revenue).

In examining and analysing the role of the accounting and production departments in the value creation process, we see that their activities are linked to Eqs. (3.8) and (3.9).

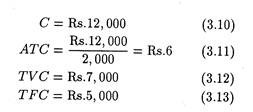

Suppose that the marketing department has assessed the market demand for X-mas cards and believes that there is an annual sales potential of 2000 cards at Rs. 4.75 each.

The accounting department, however, reports the following cost information for cards:

Total costs (C) are Rs. 12,000 with variable costs (TVC) of Rs. 7,000, fixed costs (TFC) of Rs. 5,000 and average total cost (ATC) of Rs. 6. Differently put, while the market will pay Rs. 4.75 for the card, the average cost per unit is Rs. 6. The obvious conclusion is that the firm should not produce X-mas cards, but this conclusion is, if fact, incorrect.

Why? Fixed costs are those costs incurred regardless of the level of output-rent payments on a production plant, interest payment on bank loans, heating and light bills, and minimum maintenance and repair of physical facilities.

Since it is incorrect to allocate or apportion costs to a new project if these costs would be present even in the absence of the project, we may assert that fixed costs do not affect business decisions.

The task of cost accounting is, therefore, critical to the value creation process because the decision to introduce a new product will almost always be based on a comparison of expected product price with expected costs. If fixed costs are wrongly included into an estimate of total cost, then the value creation process may be jeopardized by an incorrect decision to drop an established product or to cancel a new product.

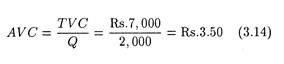

Looking again at Eq. (3.10) to (3.13) we can derive a unit cost calculation based on out-of-pocket or average variable costs:

At Rs. 3.50 of average variable cost, the product price of Rs. 4.75 for the X-mas card looks very favourable. Thus, the final cost calculation is that the X-mas card provides a contribution to overhead of Rs. 1.25 per unit (Rs. 4.75 less Rs. 3.50); alternatively, there is a price-to-variable-cost ratio of 136 per cent (Rs. 4.75 divided by Rs. 3.50).

The linkages among microeconomics, accounting and the value creation process are all based on an accurate cost analysis. Accuracy here does not refer to computational accuracy but inclusion of the correct components of cost into the estimate.

Production and Productivity Measurement:

Just as cost accounting plays a critical role in the correct assessment of out-of-pocket or marginal Costs, production plays a crucial role in the whole value creation process. Production departments are the places where industrial engineers seek to improve operational efficiency by producing the maximum amount of output from a fixed quantity of resources.

This focus on reduction of waste is an important aspect of the value creation process inasmuch as it involves the achievement of technical (or engineering) efficiency. Technical efficiency contributes to value creation by holding down unit cost.

On the contrary, economic efficiency is achieved by producing products which are valued by consumers. Economic efficiency is really in the subject area of the marketing department as it is the responsibility of the marketing people to correctly assess consumer taste and preferences for goods and services. In fact, whatever may be cost of producing a commodity no business firm will produce it unless there is demand for it.

For value creation, we must therefore produce what consumers want (economic efficiency) at the lowest possible unit cost (technical efficiency). In the late 1970s, for instance, most car manufacturers in the USA found that consumers did not want large cars (whose production resulted in economic inefficiency), nor did they want small American cars that were made poorly (technical inefficiency).

To assert that the production department helps to create value by minimizing cost per unit we revert to Eq. (3.8):

Suppose for the sake of simplicity we assume that the only variable cost is labour cost and that

Ct = AVCt .Qt + TFCt

Labour is paid a fixed hourly wage of W rupee. We can restate our definition of AVC as follows:

Wt = Wage rate per hour at time t

Qt = output at time t

Lt = labour input at time t

APLt = average output per hour of labour input at time t

Wt .Lt = labour wage bill at timet

Equation (3.15) states that average cost per unit is simply the wage rate per hour divided by average worker output per hour.

For example, if the hourly wage rate is Rs. 15 and a worker produces five units of output per hour then average variable labour cost per unit of output is Rs. 3. Equation (3.16) defines average labour productivity as output divided by hours of labour input. Substituting (3.16) into (3.15) we derive Equation (3.17).

It states that if labour is the only variable factor in the short run total variable cost is simply total labour cost, and average variable cost is equal to total wages bill divided by total output.

These three equations conjointly highlight the relation between labour productivity and wage rate and show how both are linked to the value creation process summarized in Eq. (3.2). There are two ways of raising output value per unit of labour input — either by reducing hourly wage or by raising hourly productivity of labour.

To say that a firm must try to minimize its average variable labour cost per unit is not tantamount to keeping wage rates low. According to Eq. (3.15) wage rates and average labour productivity together determine average variable cost. If wages are doubled (2W) but labour productivity is trebled (3APL) average variable cost will fall.

For example, if unionised coal miners are paid Rs. 5 per hour and produce 5 tons of coal per hour, average labour cost of Rs. 1 per ton is still higher than that generated by non-union workers who earn Rs. 10 per hour, produce 15 tons per hour and have an average labour cost of Re. 0.66 per ton.

There is no doubt that in order to maximize profit’ average variable cost has to be minimized, but this does not necessarily demand wage reduction or holding down of wages.

Economic Power and Value Creation:

As highlighted in Eq. (3.16) the production department takes the wage rate W as given and focuses on maximising productivity (minimizing waste). The wage rate W may have been arrived at by collective bargaining or it may simply reflect the going rate of unskilled labour in a purely competitive labour market.

In a like manner the market price P may be set in a monopolistic market by a dominant firm, or merely taken as given by a small firm in a purely competitive market. The existence of market power, either in the labour or product markets, thus has a strong effect on the net present value of the income stream in Eq. (3.2).

If a purely competitive firm has to face a strong union, it may be forced to raise its average variable cost to the point that average total cost exceeds the existing market price of the product. In such a situation the firm may be forced to close down its operations completely rather than produce any output at all.

Thus the value creation process suffers a setback by abnormally high labour costs — a wage rate that makes it uneconomical to hire labour. Within most companies the personnel or labour relations department is responsible for fixation and administration of wages and salaries. In a nonunionized sector wage fixation reflects the existing wage structure.

Where wages and salary negotiations are carried out with a strong union, the wage settlement may profoundly affect average variable cost and thus total costs and finally the net present value of future income stream. In a like manner, the pricing strategy of the marketing department in an oligopolistic industry may be used as a weapon to raise revenue and the NPV of the income stream.

Value Creation and the Chief Executive Officer (CEO):

In practice it is observed that the CEO is present directly or indirectly in all parts of the value creation process. The CEO, in effect, sets the direction for the company, delegates authority to the officers, and gets involved in dealing with major issues arising out of the whole process. All of these issues affect the key determinants of the NPV and would naturally be brought to the attention of the CEO.

The issue relevant for the value creation process are the following:

1. Should a new product be marketed?

2. Should a major new advertising campaign be launched?

3. Should the price of the product be raised or lowered?

4. Should management agree to the union’s wage demands or go out on strike?

5. Should a new productivity improvement programme be instigated?

6. Is the correct discount rate being used and what is the cost of capital?

7. Should cost be lowered by reducing product quality?

Thus, the CEO directly and strongly affects the value creation process by setting the parameters for all of the major questions in each of the functional areas of management.

Uncertainty and the Value Creation Process:

However, in our discussion of the value creation process so far, we have ignored an important dimension of decision making — uncertainty. That is, businesses never know for sure the value of many of the economic variables that enter into their decisions. Each of these is a time series variable inasmuch as each takes on different values at various points of time (t = 0, t = 1, t = 2, t = n).

The farther the business firm extends its analysis into the future, the greater the uncertainty concerning the probable value of any specific variable under consideration. Let us focus attention, for example, on two variables — the wage rate per hour (Wt) and the price per unit (Pt).

What will their levels be in one year (W1, P1) or five years (W5, P5) hence? Since the firm may sell its product or buy labour in imperfectly competitive product and labour markets, it will have some control over the market price of the product and the wage rate that it pays.

But control does not ensure certain knowledge of future values. Suppose a firm is currently paying workers Rs. 5 per hour, with 35% more for any time worked beyond forty hours per week.

Ignoring the per hour costs of fringe benefits (pensions, sick leave, paid holidays, medical benefit) the current average cost per hour of labour (W0) will be affected by the need to work overtime in response to unforeseeable fluctuations in sales.

Even to make a one-year projection of hourly labour costs (Wt) the firm will have to deal with uncertainty concerning the rate of price inflation in the economy, the strength or weakness of product sales, the availability of labour, and the likelihood that workers (unionized or nonunionized) will receive a different mix of pecuniary and non-pecuniary benefits (that is, wage increases versus changes in non-monetary benefits).

Even in a highly unionized labour market that fixes many of the variables contractually, there is still uncertainty about the level of needed labour (product demand is unknown), inflation (which will raise wages automatically in the same firm), and the cost of non-monetary benefits. In effect, the firm is constrained to make a probabilistic judgment concerning hourly labour costs in the next year (Wt+1)

In the opinion of Peppers and Bails, “the business firm’s constant preoccupation with the future automatically implies a parallel preoccupation with uncertainty. In a sense, uncertainty lies at the heart of the value creation and decision-making process”.

Entrepreneurs are called risk lovers because they combine resources (land, labour, and capital) with the expectation that the price that consumers are willing to pay for goods and services will be sufficient to cover the costs.

If the entrepreneur’s revenue stream is large enough, value s created and the NPV will be positive. If the entrepreneur’s forecast about the future demand for the product is wrong or incorrect, revenue will not cover cost and value will not have been created, the NPV will be negative, and the firm will be forced to close down its operations completely.

Some Fundamental Questions:

A fundamental assumption in managerial economics is that, subject to various constraints imposed by governments at different levels (the MRTP Act, the IDR Act, the Capital Issues Control Act, the FERA, the Companies Act, the Essential Commodities Act, the Supply of Goods Act, various labour laws, etc.) the firm seeks to maximize its NPV in terms of equations (3.1) and (3.2). No doubt, this statement simplifies our analysis but does not reflect the real commercial world.

So in the remaining part of the title we shall devote ourselves to expanding and modifying the statement and to show how the fundamental economic principles (such as marginalism, incrementalism, the principle of discounting, the opportunity cost concept, the equi-marginal principle and so on) can be used by the practicing manager to achieve the maximization goal.

The relevant questions that will be raised and answered in the remaining parts of the title will be the following:

1. Would the owner-manager of a business be interested in maximising the NPV of his business, or would he(she) be also concerned with his own leisure, status with the employees and people in the community to which he belongs, and other non-economic (and non-profit) issues (or matters)? Can there be any conflict of these with the basic objective of profit maximization?

2. What are the proximate determinants of NPV or profit (π) and how can the stream of profits be raised?

3. How is the rate of interest, are ‘the rate of discount, determined? By market forces or by statute (law)?

In the rest of the title we shall attempt to answer these questions, or at least provide a logical basis for answering these and related questions. Since answers to the second and third questions depend, at least partly, on market forces, it is necessary to introduce the concepts of demand and supply and link these two concepts to our basic concept (model) of value creation.

Value Creation in Supply-Demand Framework:

The basic value creation process was analysed in relation to the activities of specific departments within a business enterprise.

In a market economy, however, the value creation process is inseparably linked up with market supply and demand. So in the we attempt to make a brief review of how these two views of value creation (firm level and market level) hang together.

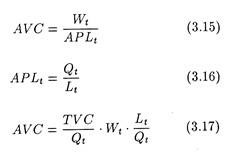

Fig. 3.2 presents a supply demand diagram for emergency lamp in one of Calcutta’s retail markets. Where does the value creation process enter in Fig. 3.2, and how is this related to our earlier analysis of the firm? The supply curve S0 is derived from the collective decisions of all the firms to supply lamps at various prices.

For example to supply ten lamps, producers want a price of Rs. 200 and consumers are willing to pay Rs. 500. The price consumers are willing to pay (Rs. 500) measures the value that they place on the last lamp produced (in this case, the tenth lamp), whereas the lamp producer’s supply price (Rs. 200) is a measure of the value of the economic resources (land, labour and capital) used up in the production of the last (tenth) lamp.

If we compare the value that consumers place on the tenth lamp with the value (cost) of the resources needed to produce the tenth lamp (Rs. 200), we observe that economic value has been created and that more lamps should be produced. In short, if output values exceed input values the firm is said to have created value.

As long as the consumers place more value on the next lamp produced than the value of the resources needed to produce it, economic value will be increased by manufacturing and selling it. This is an economic efficiency criterion so often used in micro-economics.

To achieve economic efficiency, that is, to achieve an efficient allocation of the economy’s scarce resources among lamp, bicycles, computers, and various economic goods and services, it is necessary to increase lamp production as long as this inequality holds.

P > MC

where

P = price or value of the next lamp produced to consumers

MC = marginal cost of the next lamp or value of resources needed to produce it lamp.

In fact, whatever may be the level (or intensity) of demand for a commodity no business firm will produce it unless cost is covered. A look at Fig. 3.2 reveals that for the tenth lamp the price is Rs. 300 and marginal cost is Rs. 200. Consumers want more lamps and they are willing to pay more than what it costs to produce an extra lamp, i.e., its marginal cost.

In terms of value creation or economic efficiency, how many lamps should be produced? The answer is thirty lamps at a price of Rs. 250. Why not produce 25 or 35 lamps? In this case, consumers place a value (price) of Rs. 200 on the forty-fifth lamp, but the marginal cost of producing the forty- fifth lamp is Rs. 500.

Economic value would be reduced if the lamp producer used Rs. 500 of resources and sold the lamp for only Rs. 250. This would be an instance of economic inefficiency as too many lamps would be produced and scarce resources would be wasted.

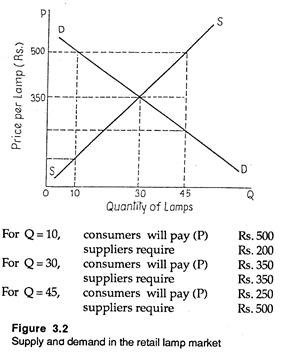

In Fig. 3.3, we summarize the value creation process for the lamp market. In this diagram we observe that consumers at last buy OF lamps at a price of OA rupees per lamp.

Thus, the area OACF represents the total expenditure of consumers, which is also the total sales revenue or turnover of the producers. In a like manner, the area OBCF measures the value of consumers of OF lamps. It may be noted that the vertical distance to the demand curve measures the value to the consumer of the last lamp produced.

Thus for OF units, the value of the last unit is the price OA (or FC). All previous units have a higher value. Thus the area under the demand curve from B to C (OBCF) measures the total value that accrues to consumers when they buy OF lamps, and the area ABC (OBCF) minus (OACF) may be called the surplus value or net gain in value to consumers when they buy OF units at a price of OA per unit.

It is observed that the lamp producers fared well in this exchange. They have received total revenue of OACF. The incremental resource cost of producing OF units is, however, OECF. Here the distance CF measures the incremental or marginal cost of the last unit.

The area under the supply curve from E to C (OECF) measures the cost of producing OF units in terms of resources used (consumed). Subtracting the cost of OECF from the revenue OACF, we get the total contribution of EAC (revenue in excess of incremental cost) that accrues to lamp producers.

There is consumer surplus value of ABC and producer surplus (contribution) of EAC. The area below the demand curve above the price line measures consumer’s surplus and the area above the supply curve but below the price line measures producer’s surplus.

In other words, total economic value created is in the amount of EBC, with part (ABC) going to consumers and part (EAC) going to lamp producers. Both sides gain from free market exchange.

In Fig. 3.3 value or wealth has been created in the amount EBC. Initially, the company produced no lamps and it had resources worth OECF. Thereafter, OF lamps valued at OBCE were produced at an incremental resource cost of OECF. Value was voluntarily created, not taken away from anyone or any group. Society had a net gain of EBC when raw materials were transformed into lamps.

All the departments within an enterprise therefore are agents of this value transformation process. Firms exist for only one reason in a free market system — to create value satisfaction for consumers at a profit. By consumer sovereignty, we mean that producers produce those commodities which consumers are willing to buy and ready to pay for.

By exercising their choice in the market place consumers may reward those firms that produce what they want.

Although many critics view capitalism as a zero- sum game in which firms gain profits only by reducing consumer welfare by an equal amount, Fig. 3.3 demonstrates a situation in which trade or voluntary exchange is mutually gainful, i.e., gainful to both the parties in a free market. Value is created not stolen, in a free market system, as predicted by socialist writers.