The below mentioned article provides a complete overview on Corporate Strategy and Long-Range Planning.

Corporate Planning and Strategy:

Long-range planning and strategy formulation is of recent origin. Since the early 1950s some large U.S. companies have introduced formal (strategic) corporate planning. At present such planning has matured to the point that firms of all sizes in the profit, as well as the not-for-profit area, make use of it routinely. In fact, the practice of corporate planning is now well established on a global scale and it continues to grow rapidly.

Virtually every reputed company in the USA and UK has a corporate planner and in the leading companies—e.g., IBM, Shell, ICI, ITI, Fiat, Ciba-Geigy corporate planning has been practiced for quite some time. It is felt that in future, corporate planning will become as much a part of management in a growing (progressive) organization as budgetary control is today.

Various benefits can be derived from a formal approach to planning. It forces a manager to think forward and make anticipatory calculations regarding the future. It provides a detailed forecast and plan that makes it easier to discover why the action taken did not produce the expected results. Also, detailed company planning enables a manager to delegate with more confidence.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As Bernard Taylor has put it, “within the framework of the plan, a subordinate can be given a fair amount of autonomy and independence, while the superior, on the other, hand retains general control”.

Concept of Corporate Planning:

Planning is a natural part of the whole management process. However, corporate planning has a special meaning inasmuch as it lays emphasis on the regular view of strategy. It can be thought of as ‘planning systematically the total resources of the company, for the achievement of quantified objectives within a specified period of time’.

However, the above definition does not properly emphasize the relation of corporate planning to strategy. In this context, Peter Drucker’s definition of corporate planning is perhaps relevant.

He defines corporate long-range planning as a continuous process of making entrepreneurial decisions systematically, and with the best possible knowledge of their futurity; organizing systematically the effort needed to carry out these decisions; and measuring the results against expectations through organized systematic feedback. Thus, corporate planning has come to mean a systematic approach to strategic decision-making.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to the Institute of Cost and Management Accountants (England), “corporate planning represents a systematic attempt to influence the medium and long-term future of the enterprise by defining company objective; by appraising those factors within the company and in the environment which will affect the achievement of these objectives; and by establishing comprehensive but flexible plans which will help ensure that the objectives are in fact achieved”.

In a progressive company corporate planning attempts to search-out or identify new areas of investment. It also makes the future a part of the current planning process so as to eliminate uncertainty. Herein lies the importance of long-range forecasting in corporate planning.

The time span covered by a corporate plan does vary from company to company and is largely influenced by such factors as the time it takes to bring new plant into operation, or develop and launch a new product. Most such plans, however, involve looking ahead by five to ten years.

Corporate planning should not be reduced to mere paper work. The whole logic of going through the detailed process of planning is to emerge with guidelines for action in the immediate future. The basic question to be answered is:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

What should management be doing now to enable it to reach the position it wants to be in, five or ten years’ hence?

Objectives and Goals:

The starting point of the whole process is a clear definition of company objectives. Companies engage in such planning just to enhance the probability that they will achieve their desired goals. If objectives cannot be clearly defined planning becomes meaningless.

There is considerable use of long-range forecasts in strategic planning. Long-range forecasting and strategy formulation usually take place at the highest levels within the organization. For strategy within the organization to be successfully implemented, the firm must have goals and objectives.

According to Drucker objectives may be set out under such headings as market standing profitability and growth, innovation, productivity, resources, personnel and community relations. Objectives may be set out in the form of performance targets for a particular function or position and may be analysed into an objectives hierarchy, or objectives and their contributory sub-objectives.

Once objectives are set and the need for goals is realized, the organization has to develop a specific strategy for reaching specific goals.

For instance, time allotments are made, budgets are fixed, machinery and equipment are acquired and installed inside the plant and all ideas of the planner are synchronized in an overall strategy that is considered to be workable at the time. At this stage the planner makes use of long-range forecasts.

As T. J. Coyne put it, “Long-run forecasting comes into being as executives attempt to determine how well and how promptly their goals will be met. It is through the forecasting process that one can determine the efficiency and effectiveness of the firm’s overall corporate strategy”.

Environmental Planning:

Once objectives have been set, there is need to scan the environment in order to identify potential threats on the one hand, and potation opportunities on the other. Forecasting environmental change is, of course, a complex exercise.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In fact, short term predictions by experts often prove to be wrong. A systematic searching of the environment ensures that unforeseen circumstances do not adversely affect the planning process.

i. Internal Appraisal:

Environmental scanning must be balanced by an appraisal of strengths and weaknesses within the company. This should be done in an objective manner, preferably by involving outsiders in the corporate planning team so that no biased view is taken of the company’s strengths and weaknesses.

However, there is no tailor-made procedure for carrying out this appraisal which all companies can adopt. It is necessary for each company to find “its own route to sound and objective appraisal of its own strengths and weaknesses, having regard to the critical factors on which business success depends in its own particular situation”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. Revision:

At this stage it may be necessary to modify the original statement of company objectives in the light of what has been discovered. This modification is directed toward making these objectives more realistic and hence more capable of achievement.

iii. Other Steps:

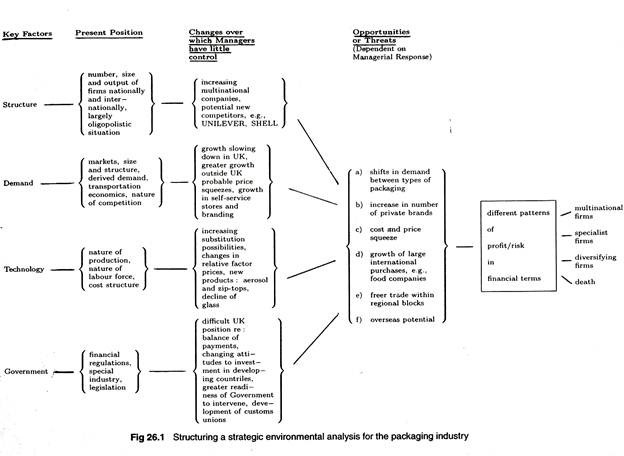

The remaining steps in the whole process of planning are summarized in Fig. 26.1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The revised corporate objectives must be related to a forecast as to where the company is likely to be n year’s hence, after taking note of threats and opportunities existing within an organization and its internal strengths and weaknesses. The forecast must then be compared with the declared corporate objectives with a view to identifying gaps or shortfalls.

At this stage the corporate plan has to be developed in such as way that it gives a clear indication of the future course of actions, including sets of sub- objectives or goals designed to close the gaps and eliminate the shortfalls.

Evaluation of Alternatives:

Effective corporate planning is dependent on the development of a corporate strategy. In reality there is often more than one possible strategy for achieving a given end result. The corporate planner is usually required to assemble the divisional plans or regions on the same basis, so that they can easily be consolidated into a five or ten years plan for the company as a whole.

But this practice robs the company of the major benefits of long-run planning—the opportunity to make a critical reappraisal of some major decisions that can exert considerable influence on the company’s future survival, profitability and growth. Therefore, at this stage, alternative strategies should be generated and compared in terms of their financial and other implications.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

An example of this may be comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of achieving growth in a given market by adopting three alternative strategies:

(1) Acquisition,

(2) Joint venture, or

(3) Investment in additional plant.

i. Synergy:

At this stage, concept of synergy can be introduced. The basic idea is that combining two or more courses of actions is more effective than pursuing them individually. In marketing, this implies that the marketing mix will make for overall effectiveness.

For example, by seizing an opportunity which makes it possible to gain increased utilization of existing marketing and distribution facilities it may be possible to raise sales revenue without causing a proportionate increase in costs. Moreover, at this stage careful consideration has to be given to the level of risk associated with alternative courses of actions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

After selecting an appropriate strategy, management must translate it into specific short-term goals or targets, for the company as a whole and for its various divisions or sub-units.

ii. Feedback:

Since planning is a continuous exercise the process does not come to a halt with the evaluation of alternatives. As the results of each year become available, or as significant changes occur in the external environment, or internally within the company, the plan has to revised, modified and updated.

Objectives of Planning:

Most companies introducing corporate planning have four objectives in mind:

1. To improve co-ordination among divisions.

2. To achieve successful diversification.

3. To ensure a rational allocation of resources.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. To anticipate technological changes.

Benefits of Planning:

A number of benefits can be derived from a formal approach to corporate planning.

Firstly, it forces a manager to think forward and anticipate problems before they occur.

Secondly, it provides a detailed forecast and plan that makes it easier to discover why the action taken has failed to produce the expected results.

Thirdly, detailed operational planning enables a manager to delegate with more confidence.

Finally, within the overall framework of the plan, a subordinate can be given sufficient autonomy and independence, while his superior retains overall control of a department or division.

Strategic Planning:

A distinction may now be drawn between operational planning as described above and strategic planning which is a systematic process for guiding the future development of an enterprise.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As B. Taylor argues. “The most important elements in strategic planning are the long-term goals set by top management and the plans to achieve those goals in a thorough and systematic way. Strategic planning helps top management, on the one hand, to anticipate and so lessen the adverse influences of a rapidly changing business environment and, on the other, to take advantage of opportunities occurring in the environment”.

The following elements of strategic planning have been identified:

1. Firstly, objectives have to be set.

2. Secondly, there is need for appraising the company’s resources and capabilities.

3. Thirdly, trends in the commercial, technological, social and political environment must be analysed.

4. Fourthly, there is need to assess alternative paths open to the business and define strategies for future development and growth.

5. Fifthly, detailed operational plans, programmes and budgets are to be produced.

6. Finally, there is need to evaluate performance against clear criteria in the light of the goals, strategies and plans established.

The strategic planning process has three distinct characteristics:

Firstly, it is not simply concerned with a particular department or division. Rather it is concerned with the development of integrated plans for the enterprise as a whole.

Secondly, it emphasizes long-term ‘strategic’ considerations as opposed to short-term ‘operational’ ones.

At this point a distinction has to be drawn between:

(a) Budgets and forecasts and

(b) Strategy which implies a thorough appraisal of the business in relation to its environment.

Finally, it envisages the setting up of formal procedures for strategic planning which run parallel to the short-term budgeting operations. Objectives, strategies and plans are put in black and white and reviewed at periodic intervals, and outside specialists are appointed to coordinate the whole planning process.

Cyone has argued that “for corporate strategy to be effective in the long-run the strategic plan (i.e., budgets, equipment, and so forth) must be devised and put in place by the manager responsible for the overall performance of a particular profit centre or plant”.

Moreover, the manager entrusted with the overall responsibility for carrying out the strategic plan must be the person most qualified to introduce needed changes over time. Therefore, the art of strategic planning is “one of setting or establishing a long-term objective that may, at the time it is set, be thought to be unreachable”.

The corporate planning manager must realize that goals, objectives and strategies are interrelated. He (she) must understand this interrelationship on the basis of which he has to develop a cohesive statement that can be readily understood by shareholders as well as divisional managers, up and down the traditional lines of authority.

This process demands constant attention and a proper sense of direction, without it scarce and costly resources of the firm have a strong chance of being misallocated. There is need for proper communication among divisional managers, functional department heads and subordinates.

Formulation of Strategy:

We have noted that corporate strategy relates to the long-term objectives and policies of the organization. It is not concerned with matters of detailed day-to-day administration, but with the overall nature of the business and how it can adapt to changing circumstances.

It has been defined as: ‘the pattern of objectives, purposes, or goals and major policies or plans for achieving these goals, stated in such a way as to define what business the company is in or is to be in and the kind of company it is or is to be’.

In fact, the determination of strategy has to be based on the existing environment of the organization and its current performance as well as on forecasts about the future.

Organizations of all types, whether explicitly or implicitly, do have a corporate strategy. For instance, an organization that wishes to secure a successful future will seek to anticipate events in both its existing and potential markets and to review the available alternatives.

Fig. 26.2 illustrates the so-called wheel of corporate strategy. The broad aims or objectives of the company lie at the centre of the wheel. The spokes of the wheel are the major policy alternatives that are available to management for achievement of the objectives.

Once the policies have been specified, and their relative importance determined, they influence, through strategy, the overall behaviour of an enterprise. As M.E. Porter puts it, “like a wheel, the spokes (policies must radiate from and reflect the hub (goals), and the spokes must be connected with each other or the wheel will not roll”.

H.I. Ansoff, the doyen of strategic writers, treats strategy as “almost exclusively concerned with the relationship between the firm and its environment and hence with the selection of the product it produces and the market it sells them in”.

However, since the range of issues considered strategic is really wide, there is need for a wider definition, too. It is in this context that Chandler defined strategy as “the determination of the basic long-term goals and objectives of an enterprise, the adoption of courses of actions and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals”.

This definition is based on his 1962 study of growth of the multi-divisional form or organization in large U.S. corporations, in response to strategic change and thus, covers diverse strategic issues.

In recent years Ansoff and others have broadened the scope of the term ‘strategy’ to cover all aspects of the relationship between the firm and its environment, rather than just the product or market mix, and thus allow a wider range of issues to be considered as strategic. For example, C. W. Hofer and D. Schendel define strategy as ‘the basic characteristics of the match an organization achieves with its environments’.

This approach enables us to consider the supply aspect of a firm’s relationship with its environment, but it fails to recognize explicitly major strategic issues that can crop up within the firm, such as its manpower and production policies.

Quite recently J. G. Smith has highlighted the point that a firm’s strategy must be implicit rather than explicit. This point has already been made by K. R. Andrews whose definition of strategy is perhaps the most comprehensive of all.

In his words, “Corporate strategy is the pattern of decisions in a company that determines and reveals its objectives, purposes, or goals, produces the principal policies and plan for achieving those goals, and defines the range of business the company is to pursue, the kind of economic and human organization it is, or intends to be, and the nature of the economic and non-economics contribution it intends to make to its shareholders, employees, customers and communities”.

In business, strategy formulation involves making decisions about the general direction and scope of their desired growth. In the words of Ansoff, “Strategic decisions are primarily concerned with external, rather than internal, problems of the firm and specifically with selection of the product-mix which the firm will produce and the markets to which it will sell”.

This is based on the assumption that the objective of the firm is to achieve a target rate of growth or to attain a certain size (as can be measured by its assets or sales turnover).

The firm has also to select the ‘business to be in’. For this, it has to set priorities for its existing resource allocations to R & D, market development, management recruiting and training, expenditure on plant and equipment, merger and acquisition.

Formulating Strategy:

The problem of strategy formulation differs from company to company. But there are certain elements or steps that can be applied in most situations.

These steps are as follows:

The on-going process of strategy formulation involves the following six steps:

1. Specification of objectives;

2. Establishment of goals;

3. Evaluation of the firm’s strengths and weaknesses;

4. A forecast of trends in the environment;

5. Delineation of economic opportunities and threats and;

6. A search for synergy (i.e., economic complementarity among potential activities of the firm).

The traditional objective of the business firm is profit maximization.

However, modern writers have pointed out that there are alternative objectives of business firms such as:

1. Sales maximization (or maximization of total revenue)—W. J. Baumol (1951);

2. Satisficing (reaching a satisfactory acceptable level of sales and profits)—H. A. Simon (1954);

3. Survival—P. F. Drucker (1958);

4. Growth for survival—J. K. Galbraith (1971).

For formulation purposes goals must be specific. A broadly-stated goal like long-term profit maximization is not very helpful. For instance, a firm’s objective may be to achieve a target rate of return on investment for the next 5 to 10 years.

However, as Ansoff has argued, even this specific goal has to sub-divided into a set of subsidiary objectives relating to external competitive strengths and internal operating efficiency. Fig. 26.3 illustrates an operationally useful set of long-range objectives. These goals are quantifiable. Therefore, the firm has to measure and forecast the extent to which these goals are being satisfied.

Ansoff has also referred to a related point. Profit-maximization is related to an additional objective, viz., flexibility: internal and external.

While internal flexibility is provided by liquidity, external flexibility is gained through diversification. Risk reduction is achieved through both the methods. These two methods help to ensure that profits are not wiped out by a single adversity (such as a sudden fall in the demand for a single product).

The loss incurred due to fall in the demand for one product is recouped by a steady rise in the sale of other products in the product line. Moreover, a firm having unutilized borrowing power can meet the threat of a sudden and unexpected product improvement by a competitor.

A closer scrutiny however, reveals that the two objectives, viz., profitability and flexibility are often conflicting in nature. So a compromise has to be reached between the two. Moreover, flexibility can be attained only at the cost of profit. Agreement has to be reached within the business firm regarding these two objectives.

For instance, a reduction in investment expenditure, i.e., expenditure on plant and equipment will allow an increase in assets that can be quickly converted into cash so as to improve the liquidity position of a firm in a year of bad business (when there is temporary demand recession).

Both objectives may be subject to self-imposed responsibilities and institutional constraints. In some situations management may discharge its social responsibility of providing steady employment and job security to old employees even at the cost of profitability.

Selecting the ‘business to be in’:

Choosing ‘the line of business to be in’ is one of the most important strategic decisions. A firm also strives to evolve a product-mix and a corresponding set of markets that seem to offer the best prospects for achieving its objectives. It has to compare various possible ways to utilizing its limited (but to some extent unique) resources and organizational competences.

Strategy formulation is based on:

(1) Appraisal of the firm’s strengths and weaknesses,

(2) Determination of the particular business competence that are essential for success in various growth areas, and

(3) Forecasts of the results of successful operations in a line of activity.

There are two ways of appraising:

(1) The firm’s relative strengths and weaknesses by an examination of past performance to identify areas of success or failure and

(2) By direct comparison of the firm’s skills and competence with those of major rivals.

In the words of J. B. Quinn, “The purposes of such exercises, to marshall sufficient resources into specific sub-areas of the company’s operations, to dominate them, to recognize where competitive strengths allow the company wider latitude in pricing or product policies than competitors, and to pinpoint the company’s own weakness for more aggressive action or purposeful withdrawal”.

There are five key areas in which most company’s strengths and weaknesses can be assessed:

1. Use of financial resources;

2. Profitability;

3. Functional strengths and weaknesses;

4. Product range; and

5. Human resources and organization.

This process should cover all of the resources and competences required in the present business of a company, as also other capabilities that it has or can reasonably expect to acquire. The table below presents a list of a various factors to be considered in such an appraisal.

Outline for internal appraisal and industry analysis:

1. Product-market structure:

a. Products and their characteristics.

b. Product missions.

c. Customers.

2. Growth and profitability:

a. History.

b. Forecasts.

c. Relation to life cycle.

d. Basic determinants of demand.

e. Averages and norms typical of the industry.

3. Technology:

a. Basic technologies.

b. History of innovation

c. Technological trends-threats and opportunities.

d. Role of technology in success.

4. Investment:

a. Cost of entry and exit—critical mass.

b. Typical asset patterns in firms.

c. Rate and type of obsolescence of assets.

d. Role of capital investment in success.

5. Marketing:

a. Means and methods of selling.

b. Role of service and field support.

c. Roles and means of advertising and sales promotion.

d. What makes a product competitive.

e. Role of marketing in success.

6. Competition:

a. Market share, concentration, dominance.

b. Characteristics of outstanding firms.

c. Trends in competitive patterns.

7. Strategic perspective:

a. Trends in demand.

b. Trends in product-market structure.

c. Trends in technology.

d. Key ingredients in success.

Such a systematic and through appraisal serves four essential purposes in the corporate planning process. Firstly, it enables management to identify potential assets and opportunities that can be exploited. Secondly, it helps management to determine the basic immediate changes in structure and policies necessary if long-term objectives are to be achieved.

Thirdly, it makes possible an increase in immediate profitability and liquidity by the more effective use of the company’s existing resources, thus providing a more stable base for the development and achievement of long-term objectives. Finally, it helps planners prepare defensive strategies by which the risk to earnings, and cash-flows through external factors, can be minimized.

These methods can be adopted for determining business success in various industries:

(a) Preparing a exhaustive list of technological, marketing, financial and management capabilities required by the nature of each industry and

(b) By developing competitive profiles of the most successful firms in each industry.

Then, as Ansoff argues, “Superimposition of one firm’s competence profile with the competitive profiles measures the ‘fit’ with each new industry, and hence the chances of a successful entry”.

Finally there is the obvious need to forecast the results of successful business operations in the various industries in order to choose a ‘portfolio’ of businesses-to be in. Such forecasts are to be based on estimates of growth prospects, return on assets used, and year-to-year variability in sales and income, assuming that the firm is a competent organization, in each line of activity (business).

Such estimates, in their turn, are based on “projections and analysis of trends affecting demand for products and services, competition, the institutional and legal environment, timing and nature of technological changes, availability and relative cost of resources, and increases in industry capacity.”

Technological Planning:

Formal methods of technological forecasting have been developed very recently. Most of these techniques have been developed in the 1960s.

In fact, technology is nothing but systematic application of knowledge. This knowledge does improve in small increments, or scientific breakthrough is just an accumulation of small advances that add up to a significant change.

Two Views:

There are two different views on technological change. The scientists view inventions as occurring independently of external circumstances or needs. Consequently they rely on exploratory forecasting. They start with existing technology and on the basis of it, project potential progress and then consider how these changes may affect the nontechnical business environment.

In other words, such forecasting starts by mapping technological possibilities out toward their limits. Non-technical people hold an opposite, view of technological progress. They see it as a response to external non-economic forces that create new demands for goods and services to satisfy new wants.

They rely on normative forecasting, in which forecasters start by predicting the future needs and objectives of society. They then work back to the current state of technology with a view to determining the gaps that have to be closed so as to satisfy emerging needs and aspirations of society.

Normative forecasts are often criticized on the ground that even the most widely recognised needs of society do not always call forth an invention. But such forecasts have the obvious advantage that they extend further into the future than do exploratory methods. On the contrary, exploratory forecasts are criticized on the ground that they fail to take account of the probable further desires of the society.

But such forecasts have two major advantages:

(1) They are relatively simple and

(2) They do focus on technological issues. So it is always better to combine the two methods so as to achieve the best result.

As E. Jantsch has pointed out, “A complete technological forecasting exercise . . . always constitutes an interactive process between exploratory and normative forecasts . . . it constitutes a feedback cycle in which both opportunities and objectives are treated as adaptive inputs”.

Forecasting Techniques:

There are two major techniques of technological forecasting whose primary interest is to determine the probability that selected end results will be achieved, and to evaluate their significance.

Two intuitive forecasting techniques are: the Delphi method and scenario writing.

The Delphi Technique:

Technological forecasting is a term used in connection with the longest term predictions and the Delphi technique is the methodology often used.

The objective of the Delphi technique is to probe into the future in the hope of anticipating new products and processes in the rapidly changing environment of today’s culture and economy. In the shortest range covered by this technique, it can also be used to estimate market sizes and timing.

The technique draws on a panel of experts and attempts to gain the benefit of expert opinion in the form of a consensus rather than a compromise. The result is pooled judgement showing the range of expert opinions and the reasons for differences of opinions.

The Delphi technique was first developed by the RAND Corporation as a means of eliminating the undesirable effects of group interaction that may occur in conferences and panels where the individuals are in direct communication.

The panel of experts can be constructed in various ways and often includes individuals both inside and outside the organization. It may be true that each panel member is an expert in some aspect of the problem, but no one may be an expert on the entire problem.

In general, the procedure involves the following:

1. Each expert in the group makes independent forecasts in the form of brief statements.

2. A coordinator edits and clarifies these statements.

3. The coordinator provides a series of written questions to the experts that combine the response of the other experts.

One of the most extensive probes into the technological future was reported by TRE, Inc. The project involved the coordination of 15 different panels corresponding to 15 categories of technologies and systems that were felt to have an effect on the company’s future. Anonymity of panel members was maintained to stimulate unconventional thinking.

The Delphi method was then used to question and re-question the experts. The result was a composite rating of each event on the basis of its desirability, its feasibility, the probability that the event would occur, and probability estimates of the timing of occurrence.

The extensive results of the project were then formed into logic networks. One such network shown by North and Pyke shows the milestone events that had to precede the technical achievement of holographic color movies.

Holography is an optical projection technique that gives the viewer the illusion of the third dimension. The network also showed events that were likely to occur, as “fallout” from the basic developments.

Scenario Writing:

Scenarios are predictions rather than forecasts because they are expressed in ‘if’, ‘then’ form. Scenario writing produces “narrative, time-ordered, logical sequences of events. Each such scenario is a description of a possible evolving future environment.

Scenarios can be used as inputs to a forecasting technique or vehicles for communication among forecasters”. Corporate planners must use some form of technological forecasting that involve technological developments within the relevant planning horizon.

Pitfalls:

However, technological forecasting is not free from defects.

J. B. Quinn has identified major pitfalls of such forecasting:

1. Unexpected interactions of various coincidental and apparently unrelated advances;

2. Unexpected demands, such as new sources of energy for industrial use;

3. Major discoveries of entirely new phenomena; and

4. Inadequate data concerning scientific resources committed to various lines of R & D.

Technology and Resources:

However, changes in technology are very much responsive to changes in relative prices of natural resources. If prices of some major resources rise because of relative scarcity, there is search for substitutes and for other methods for economizing the use of such scarce resources.

On the contrary, if prices of certain other resources start falling because of abundance, there is thorough-going search for new technological uses of the plentiful inputs. Thus, resource forecasting and technological forecasting go hand in hand.

Resource Forecasting:

Since business firms make use of various resources it is necessary to forecast, in economic terms, demands and supplies of various resources. The needs and availabilities of various resources determine their relative prices and thus affect the choice of methods of production and finally relative prices of final goods (because prices of commodities and resources are interrelated).

The cost and prices of various products are affected by energy costs inasmuch as various types of energy, and sources of energy at different places, will affect choices of plant locations, production techniques, and product mixes.

Corporate planners are especially interested in forecasts of changes in relative prices of inputs. Since the demand for resources in derived demand, if the demand for motor cars in India increases, there will be more demand for steel (and thus of iron are, coal, coke and heat).

There will also be rise in the demand for electric power from diverse sources as hydroelectric generators, coal and nuclear energy. A substantial amount of power is required in steel production. If steel production declines, the demand for electricity and for electric power-generating plants will also fall.

Merger and Acquisition:

On the basis of competitive strategy and long- range planning a firm is able to determine the proper ‘business to be in’.

Two major factors influence this decision:

(1) The maturity of the industry and/or

(2) The maturity of the particular product being manufactured.

Industry Maturity:

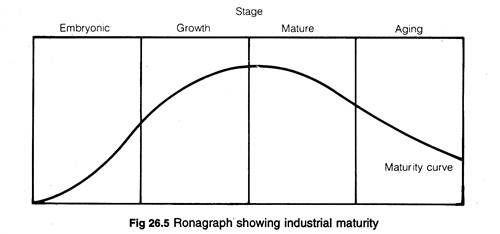

Every industry passes through four distinct, but interrelated phases as illustrated in Fig. 26.3, viz.,

(1) Embryonic,

(2) Growth,

(3) Mature, and

(4) Aging.

In fact, the maturity of an industry is calculated by comparing cash outlay to cash inflow, expressed as a percentage. This figure is called a Ronagraph and is presented in a simple form in Fig. 26.5.

The Ronagraph is a very important concept inasmuch as it highlights the point that in business or industry everything passes through an evolutionary process. Products which were extremely valuable for a company a decade ago may not be that attractive today.

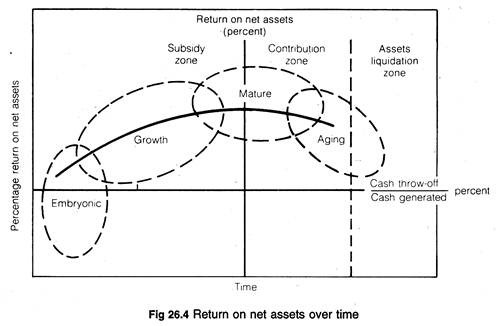

From the profitability points of view copyrights and patents are obvious examples of very profitable, or at least potentially profitable, items having a limited life cycle. Fig 26.6 illustrates the position of a firm whose performance has been quite satisfactory in the past but now finds itself in the latter phase of the mature stage or the beginning phase of the aging stage, as Fig. 26.4 and 26.5 indicate.

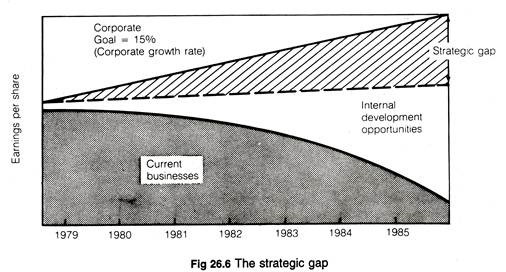

The Strategic Gap:

Consider a progressive organization whose objective is to emerge as the most profitable firm in the industry. Suppose it has set for itself a corporate goal of obtaining a corporate annual growth rate of 15% measured in terms of earning per share.

If the product of the firm has already reached the mature stage of its growth cycle, the state of firm’s recent operations can be illustrated by the shaded area in the bottom half of Fig. 26.6. Even if the firm is efficient and its products are of high quality, its earnings per share must decline simply because its product(s) has (have) reached its (their) aging stage.

To overcome this problem the firm may try and succeed in achieving as much internal development as possible. But this may be far from adequate and a wasteful strategic gap may develop within the enterprise. This gap arises because the firm is unable to achieve its target of a 15% growth rate.

A pragmatic solution to the problem lies in acquiring another firm or merging with another firm. Mergers and/or acquisitions are directed toward raising the returns to the corporation thereby closing the strategic gap.

The acquisition need not necessary be in the same industry. A company can diversify its activities as well. And diversification is an important and effective component of a company’s strategic plan.

Nevertheless acquisition may raise the return to a firm in one or more of the following ways:

Merger and/or acquisition often brings with it special skills and knowledge of the industry possessed by one partner, who can apply this knowledge and these skills to the competitive problems and opportunities facing the other partner. Consequently there is an improvement in the productivity of capital.

If investments are made in markets closely related to the current filed of operation of the most powerful partner, long run average cost of production will fall with an expansion in the scale of operation of the larger firm.

A corporation can beat the competitors if expansion in one area of competence leads to development of critical resources. If for instance, a cement manufacturing company acquires another company producing limestone, it will enjoy cost reducing advantages.

It is possible to make optimum utilisation of working capital by shifting cash from units having cash surplus to units having cash deficits.

A new diversified firm can switch its cash resources from old and well-established products to new products that might be in the growth stage of its life cycle. This strategy might improve the long- run profitability of the new firm.

Finally, risk reduction can be achieved through diversification. By pooling risks a company can reduce its cost of debt and, consequently, its overall cost of capital. At the same time financial and operating leverage considerations can be made to operate for the benefit of the new diversified company.

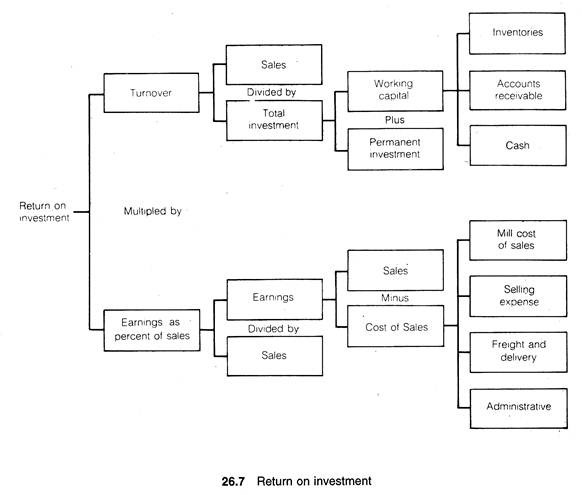

If the operation of the new company goes well, its profitability or return on investment, as shown in Fig 26.7, can be improved.

If return on investment rises and if the dividend policy of the firm is not materially and adversely affected, the earnings per share can be improved and strategic gap closed. A basic point about acquisition is that control over a larger amount of resources by heading a larger firm is likely to confer direct benefits to managers in terms of their emoluments and industrial and social standing.

Conversely, the top management in the company acquired may lose their independence of action. Ambitious managers, however, see take-over as a quick route to expansion, with all the potential managerial benefits involved, rather than internal investment.

For the employees’ point of view the benefits of acquisition depend on whether any such advantage takes the form of economies of scale and manpower saving, as opposed to more rapid expansion through faster and more successful development.

Diversification:

Diversification occurs “when the firm moves into new areas of activity which are not vertically related to each other. There may, however, be links between the activities in that they have common inputs or the same distribution channels”.

J. Bates and J. K. Parkinson have distinguished between two broad types of diversification:

1. Narrow spectrum—where the activities have close production or marketing links:

2. Broad spectrum—where the new activity is completely unrelated to the acquiring of other companies, already engaged in other fields.

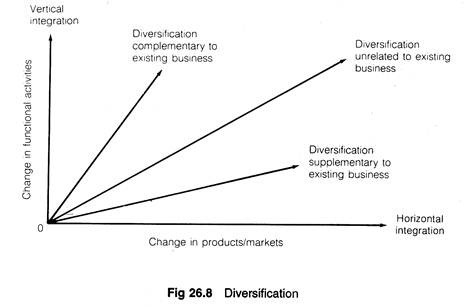

Diversification is simply the process of expanding the business activity into related, or previously unrelated, areas. Diversification should serve to create additional value for the shareholders. It can be accomplished via vertical or horizontal integration, as depicted in Fig. 26.8.

The combined resources of two companies should give rise to a net cash flow and/or income stream for the combined company, that is significantly greater than the flows or income that could be realized from the two companies if viewed separately. Theoretically, a corporate acquisition programme results from the corporate strategic planning effort.

The incentive to diversify exists only if the firm happens to possess an asset or assets such as capital, managerial expertise and innovative ability that provide the capacity to operate in more than one industry. Many modern economists see diversification merely as one aspect of the reasons for the emergence of multi-product firms.

Often technological factors account for the emergence of multi-product firms, or multi-industry production, incurring lower costs than under specialization. Bates and Parkinson have called these economies ‘economics of scope’ which are different from ‘economics of scale’.

Such scope economies occur “when joint production of two goods by one firm is less costly than the combined costs of production by two specialized firms . . . if such economics exist it is cheaper to add an additional product to an existing range (through, e.g., diversification) than to produce that particular product on its own”.

For such economies to exist two conditions must be satisfied:

(1) Firstly, there must exist some resources that can be shared by more than one product; and

(2) Secondly, “either the input involved must be large and indivisible, so that they cannot be fully utilized by one product alone, or an input brought for the production of one product must be available for use in another. In the latter category, skilled general management is perhaps the most obvious example.”

Most modern business firms are multi-product firms. In such firms scope of economies are universal. The existence of such economies creates a strong incentive for diversification if the main product of the firm cannot fully utilize these assets.

There are three major arguments for diversification: growth, market power and risk avoidance.

Growth:

Diversification for growth or even to preserve the existence of the enterprise may be linked to the life cycle of a product. Thus, as the company’s main product reaches the maturity stage and profit and sales potential decline, it becomes necessary to consider the possibility of introducing new products in the product line.

In this context one may distinguish between two types of diversification: Cost-push and market-pull. Cost-push diversification occurs when the primary activity of a firm is unable to use fully the capital resources of the firm, without a sharp fall in profitability.

Thus, if sufficient investible resources are available and are not required for the defence of an existing market position, the incentive to diversify will grow with a fall in the growth rate of the firm’s primary activity.

On the contrary, market-pull diversification occurs “when the firm perceives an opportunity for diversification before it is forced to a reappraisal of its market position by declining profitability. The perception and realization of such opportunities may be greater, the higher the importance of research and marketing functions within the organization”.

There are various possible effects of diversification on market power. Suppose a company already possesses market power in one activity. It may then be able to extend its power into other markets through such devices as tie-in sales, cross- subsidization and reciprocal buying.

Tie-in sales (also known as full-time forcing) refer to the practice of selling new products of a company to the intending purchaser of its well established product. In other words, the purchase of an old product is made conditional on the purchase of a new product. For example, Godrej may force its distributors to buy its shaving cream along with Cinthol.

The Horlicks Company may force consumers to buy biscuits along with Horlicks. This practice often enables the diversified firm to introduce some sort of differential pricing and extract greater profit from the market.

Cross-subsidisation involves the use of profits in one market to subsidize sales in another market with the objective of driving other producers out of the market and achieving greater profit and sales in the long run. For example, a company can sell pressure- cookers or bicycles at lower prices in rural areas and may charge higher prices for the same products in urban areas.

Finally, reciprocal buying arise when two diversified firms reach a mutual agreement to buy from each other rather than from a third party. No doubt, the above three practices do provide some incentive for a diversification strategy when a firm already possesses some market power.

The strategy of diversification is often supported on the ground that by spreading the company’s activities, it may provide greater long-run security and a more stable cash flow. But this is achieved at the cost of greater returns that could be earned by the adoption of greater specialization in activities with the largest potential returns.

However, the decision to diversify or specialize largely depends on the attitude of management toward risk. One strong argument in favour of diversification is that “it can help to even out cash flow that is affected by seasonal or cyclical factors, where the timing in the two or more activities is complementary.”

A final point may be noted in this context. The shareholders, the ultimate owners of the company, can reduce the risk to which they are subject to by buying the shares of a number of companies and holding a mixed portfolio. But, unlike shareholders, the management of a company is not, in general, able to spread their risks by switching the company’s portfolio of assets so easily and quickly.

Vertical Integration to Gain Market Power:

Firms may choose to integrate vertically to achieve market power. Some firms choose to produce some of their own inputs rather than rely on markets for two reasons: the pursuit of market power and cost reduction. In the first hypothesis, firms may seek market power in order to engage in monopoly-like behaviour.

In the second, firms may produce some of their own inputs because the costs of market transactions exceed the benefits of using the market.

When a firm produces some of its own inputs, say iron-ore, it is a vertically integrated firm. Vertical integration is the consolidation of production of inputs and outputs under the control of the same firm. The second hypothesis focuses on the cost- reduction potential of vertical integration.

Market Foreclosure:

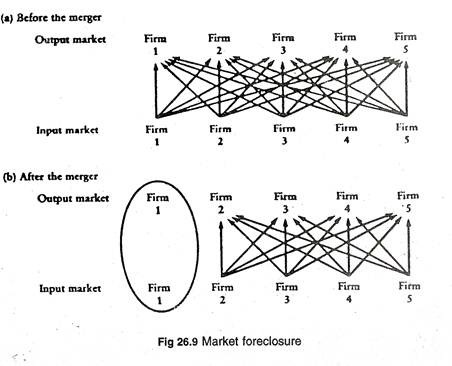

The following figure shows how vertical integration can increase the costs of entry and lead to market foreclosure. Market foreclosure is said to occur when a firm or group of firms succeed in creating insurmountable barriers to market entry.

Let us consider a market in which there are five firms supplying an input to an industry that also contains five firms using this specialized input. If the two groups of firms maintain their separate identities, there may be sufficient competition among the suppliers to insure a competitive price for the input. Such a possible pattern of trade is shown in Fig. 26.9.

As a result of the merger of a supplier and a buyer there is loss of opportunities for the remaining independent firms. If each of the firms supplying the input merges with a firm in the other industry, no independent suppliers or purchasers will be left in the market.

A new entrant to the market may find it not only difficult, but virtually impossible, to enter the market, either as a supplier or as a buyer of the input. A new firm is left with only one option: to enter as a fully integrated firm operating at both levels in the vertical chain.

Since this larger-scale operation will involve a greater investment, this added cost erects an extra barrier to entry. Furthermore an entrepreneur with expertise in only one area of the vertical process may be reluctant to enter without expertise in the other area.

Bilateral Monopoly:

An extreme form of imperfect competition is bilateral monopoly which refers to the situation when there is a single seller of a product who faces a single buyer in the market.

As James Mulligan has commented, “when there is a sole supplier and a sole buyer there is no unique market-determined output or price. Instead, there is a negotiated market solution. While bilateral monopoly represents the purest form of market imperfection, the following analysis will be relevant as long as both buyer and seller have some market power relative to one another”.

It is quite reasonable to assume that there are strong barriers to entry, since we have to firms with established monopoly position. The following diagram shows that the two firms have an incentive to coordinate their output levels.

Consider the Indian car market. Suppose Hindustan Motors discovered that PAL makes its own car bodies but buys its other inputs, such as tires, from other firms.

To see why PAL has chosen to make its own car bodies, let us assume for a moment that PAL does not make its own car bodies, but buys them from another firm, Standard Motors Ltd. Assume that Standard Motors has a monopoly on the sale of this type of car body, and that PAL is the only buyer.

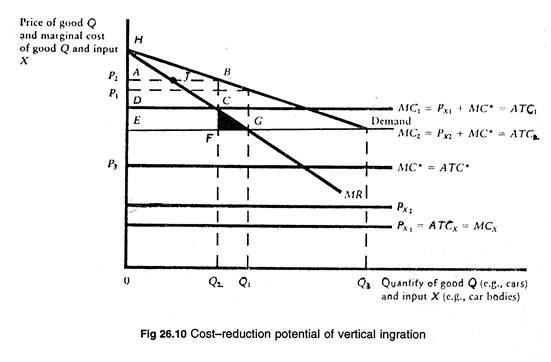

We will assume that PAL buys all of its inputs except car bodies in perfectly competitive markets. The marginal cost of producing the sports car excluding the cost of the car body, is MC*. For the sake of simplicity let us assume that MC* is constant at all output levels and is equal to the average total cost, ATC*.

In Fig. 26.10, we assume that PAL faces demand curve D for its sports car. For purposes of comparison assume that Standard Motors sells its car body to PAL at price PX1, which equals the average and marginal cost of producing a car body. The marginal and average total cost of producing the sports car is the sum of MC* and Px1 = MC1. If PAL produces the car with marginal cost MC1, it produces output Q1 and charges price P1.

Being able to recognize its potential market power, Standard Motors (SM) is not content to charge a price that just covers its average cost of production. Assume that it decides to maximize its profits by raising its price. We will ignore the details of how SM is not content to charge a price that just covers its average cost of production.

Assume that it decides to maximize its profits by raising its price. We will ignore the details of how SM determines this price, and simply assume that it decides to raise its price to Px2. The marginal cost of producing the car now increases to MC2 = MC* + Px2. Hindustan Motors produces output Q2 where marginal revenue equals the new marginal cost.

PAL’s economic profits is the difference between total revenue and total cost. For example, since area HCQ20 measures total revenue at output level Q2 (the area under the marginal-revenue curve), profits will be area HCD (area HCQ20 minus area DCQ20). SM receives (PX2 – PX1), SM’s profits equal area CDEF.

If the two firms operate independently, there combined profits will be less than if they merge. By merging they will consider the true cost of producing the car to be MC1: the actual production cost the car body (PX1) plus the cost of the other inputs (MC*).

Profit maximization will occur at Q1. Since total revenue is the area under the marginal- revenue curve, the net gain in overall profits for the new vertically-integrated firm will be the triangle, FCG, i.e., the difference between the changes in total revenue (area CGQ1Q2) and total cost (area FGQ1,Q2).

By merging, the two firms may succeed in eliminating market imperfection caused by the market power of the two firms. The combined firm will produce cars where MR equals the true marginal cost of Q. The merger will benefit customers buying cars, due to the fall in the market price of cars, and the increase in quantity sold.

It may, however, be noted that if neither firm has any market power, the markets for car bodies and cars will be perfectly competitive, with a much greater market output of Q3 and a lower price equal to marginal cost MC1.