In this article we will discuss about the various financial assets of a commercial bank.

Liquidity and Profitability:

In order to be able to meet demands for cash as and when they are made a bank must not only arrange to have sufficient cash available but it must also distribute its assets in such a way that some of them can be readily converted into cash.

Thus, the bank’s cash reserves can be reinforced quickly in the event of heavy drawings on them. Assets which are readily convertible into cash are called liquid assets, the most liquid being cash itself. The shorter the length of a loan the more liquid because it will soon mature and be repayable in cash; the less profitable because, other things being equal the rate of interest varies directly with the loss of liquidity experienced by the lender.

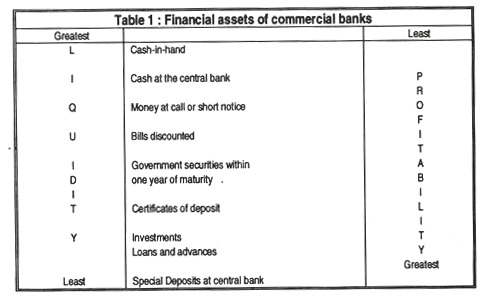

Thus a bank faces something of a dilemma in trying to secure both liquidity and profitability. It satisfies these apparently incompatible requirements in the way it distributes its assets. These assets have been arranged in the following table with the most liquid but least profitable ones at the top and the least liquid but most profitable towards the bottom.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The rupee assets of the banks include the notes and coin held in their vaults and the bankers’ balances at the Central Bank are part of the banks’ reserves. The bankers’ balances at the Central Bank are a bit like your own deposit at a bank.

Just as you sign cheques to pay your debts or expenditures, banks will meet their balances at the Central Bank. The banks also hold some liquid assets and these are loans to financial intermediaries, government bills and other securities.

These liquid assets earn a rate of interest, but banks make the most of their money by giving loans and overdrafts to people and business. These items come under the heading of advances. The banks also make money by lending in other currencies to businesses, other banks and governments.

Cash-in-Hand:

It represents a bank’s holding of notes and coins to meet the immediate requirements of its customers. Nowadays, there is no limit set on the amount of cash which banks in India must hold and it is taken for granted that they will hold enough to maintain their depositors’ confidence. The general rule seems to be to hold something in the region of 4% of total assets in the form of cash.

Cash at the Central Bank:

It represents the commercial banks’ accounts with the central bank. When banks in India require notes or corns they obtain them from the Central Bank by drawing on their accounts there in the same way as their customers obtain it from them. The banks also use their central bank accounts for setting debts among themselves. This process is known as the clearing system.

Money at Call and Short Notice:

This consists mainly of day-to-day loans to the money market but also includes some seven-day and fourteen- day loans to the same body and to the stock exchange. This asset is by nature very liquid and enables a bank to recall loans quickly in order to reinforce its cash.

Being so very short these loans carry a very low rate of interest; consequently they are not very profitable. The money market consists of discount houses. Then, main function is to discount bills of exchange.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These bills may be commercial bills, or Treasury Bills. A bill is a promise to pay a fixed amount usually in three months’ time. Thus a firm, or the Treasury, can borrow money by issuing a promise to pay in three months. A discount house may buy such a bill at a discount, i.e., it may buy a Rs.100 bill for Rs 90.00. In this case the rate of discount is 10% (per annum).

This discount house may later sell the bill to a bank, i.e., rediscount it, but when it matures the bill will be presented for payment at its face value. The discount houses finance their operations by borrowing ‘on call or at short notice’ from the commercial banks and they make their profits out of the fractional differences between the rates of interest they have to pay the banks and the slightly higher rates they can charge for discounting bills.

Bills Discounted:

Another link between the banks and the money market lies in the way in which the banks acquire their own portfolios of bills. By agreement the banks do not tender directly for these bills but instead buy them from the discount houses when they have two months or less to run. They also buy them in such a way that a regular number mature each week, thus providing an opportunity for reinforcing their cash bases.

Thus, the money market provides two notable services to the banks. It enables them to earn some return on funds which would otherwise have to be held as cash and it also strengthens their liquidity as regards their bill portfolios.

Government Securities with One Year or Less to Maturity:

These securities consist of central government stocks and nationalised industries’ stocks guaranteed by the government. Since they are so close to the date when they are due for redemption, i.e., repayment at their face value, they can be sold for amounts very near to that value. Thus banks can sell them to obtain cash without suffering any loss. They are very liquid assets.

Certificates of Deposit:

These are receipts for specified sums deposited with an institution in the banking sector for a stated period of up to five years. They earn a fixed rate of interest and can be bought and sold freely.

Investments:

These consist mainly of government stock which is always marketable at the stock exchange, even though a loss may be involved by a sale at an inopportune moment. The classification of investments as more liquid than advances can be justified by the greater ease with which investments can be converted into cash, for the latter, although they can technically be recalled at a moment’s notice, can in fact only be converted into cash if the borrower is in a position to repay, and, of course, at the risk of the bank losing its customer if any inconvenience is caused.

Loans and Advances:

These are the principal profit earning assets of the commercial banks. They composed mainly of customers’ overdrafts whereby in return for interest being paid on the amount actually drawn, banks agree to customers over-drawing their accounts, i.e., running into debt, up to stated amounts. These facilities are usually limited to relatively short periods of time, e.g., 6 to 12 months, but they are renewable by agreement.

Special Deposits:

These may be called for the central bank when it wishes to restrict the banks’ ability to extend credit to their customers. Conversely, a release of existing special deposits will encourage bank lending. As any release of these deposits depends entirely on the central bank they are illiquid and, as they carry only a low rate of interest, they are not profitable assets.