Read this article to learn about the money supply and credit creation by commercial banks.

It will be seen that the most important function of a commercial bank is the creation of credit money—a function which overshadows all other banking functions.

Credit creation or money creation refers to the power of the banks to expand or contract demand deposits through the process of more loans, advances and investments.

Some writers express the view that a bank could never lend more than the amount deposited by the depositors; this may be partially true.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But it is also true that whatever is lent out by a bank may come back by way of new deposits, which may be lent out again and so on, a deposit becoming a loan which again returns to the bank as a deposit and becomes the basis for a new loan and so on.

A commercial bank, therefore, has been aptly described as a ‘factory of credit’, which is able to multiply loans and investments and hence deposits. With a little cash at the disposal they are able to create additional purchasing power to a considerable degree. It is in this sense that banks create credit. An increase in bank credit will, therefore, mean multiplication of bank deposits.

There are mainly two ways of creating credit money by a commercial bank:

(a) By giving a loan, and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) By purchase of securities.

(a) By giving a loan:

Let us assume an isolated community having no foreign trade relations and only one bank where everybody keeps an account; further no cash circulates and transactions are settled by cheques. Bankers know that all the currency that depositors withdraw soon returns to the bank. They also know that all depositors will not withdraw all deposits at the same time. From experience they have learnt that if they just keep about 20% of their total demand deposits in cash reserves, they will have enough to meet all demands for cash.

Suppose an ordinary borrower goes to the bank for a loan of Rs. 1,000. After being convinced of the solvency of the borrower and the safety of the loan in his hands, the bank will advance a loan of Rs. 1,000 not by handing over cash or gold to the borrower, but by opening an account in his name. If the borrower, already has an account, he will be allowed an overdraft to the extent of Rs. 1,000.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, the most usual method of making a loan is merely to credit the account of the borrower with Rs. 1,000. The borrower will then draw cheques on the bank while making purchases. Those who receive the cheques deposit them with the banks in their own accounts. Therefore, a bank loan of Rs. 1,000 has resulted in deposits of Rs. 1,000. The point to be noted and understand is that loans are made by creating a deposit.

When a person deposits Rs. 1,000 with a bank, the bank does not keep the entire cash but only a certain percentage (say 20%) of it to meet the day-to-day cash obligations. Thus, the bank keeps Rs. 200 and lends to another person B, Rs. 800 by opening a credit account in his name. Again, keeping 20% to meet B’s obligations, the bank advances the rest Rs. 640 to C ; further keeping 20% to meet C’s obligations the bank advances Rs. 512 to D and so on, till Rs. 1,000 are completely exhausted.

Thus, an original deposit of Rs. 1,000 leads to additional deposits of Rs. 800 plus Rs. 640 plus Rs. 512 plus Rs. 409, plus Rs. 328 and so on. By adding up all the deposits we get total Rs. 5,000. It is clear, therefore, that the total amount of credit creation will be the reverse of the cash reserve ratio. Here cash reserve ratio has been assumed to be 20% or 1/2, therefore, the credit is Rs. 5,000 i.e., live times the original deposit of Rs. 1,000. Although, we have assumed one bank, yet the credit creation will take place when there are many banks.

It is clear that the main limitation on credit creation is the reserve ratio of cash to credit. Therefore, the amount of credit that a system of banking can create depends upon the reserve ratio. The banks can multiply a given amount of cash to many times of credit. If the public would demand no cash, credit would go on expanding indefinitely. But the reserve ratio is a sort of leakage from the Stream of credit creation.

We can, thus, think of a credit creation multiplier. The higher the reserve ratio, the smaller is the credit creation multiplier. In our example above, with an original deposit of Rs. 1,000 the bank was in a position to create credit of Rs. 5,000. The credit creation multiplier is obviously 5(Rs 5,000/Rs,1,000).

In general, the credit creation multiplier is related to the reserve ratio in the following way:

1/1-(1-reserve ratio) = 1/reserve ratio

If the reserve ratio is 1/3, credit creation multiplier is 3 a reserve ratio of 1/5 will give us a higher value 5.

(b) By purchase of securities:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Making loan is not the only way in which deposits can be created. Sometimes, banks buy securities at the Stock Exchange and also buy real assets. When the bank does so, it does not pay the sellers in cash, rather it credits the amount of the price of the security or assets to the accounts of the sellers. The bank, therefore, creates a deposit with it.

It does not matter whether the seller of securities or property is a customer of the purchasing bank or not, as the seller is bound to deposit the cheques he receives in one of the banks. The purchase of security by any banker is bound to increase the deposits either of his own bank or of some other bank, in any case, the deposits of the banking system as a whole.

Multiple Credit or Money Expansion:

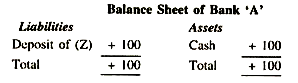

This process can also be shown in ‘T’ form. Suppose Mr. Z, who is a government employee gets his pay cheque of Rs. 100. The cheque is used by the government is drawn on R.B. of India. Let us assume Mr. Z has an account in Bank ‘A’ in which he deposits the cheque. Bank ‘A’ presents this cheque to RBI for collection, as a result of which, the deposits of Bank ‘A’ increase by Rs. 100 and its cash will also increase by Rs. 100.

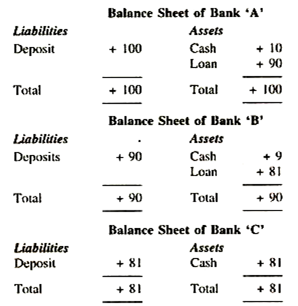

The balance sheet of Bank ‘A’ (in T form) will be as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

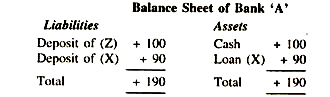

By experience Bank A finds that Z will need hardly 10% of it in cash. It means Bank ‘A’ can lend Rs. 90%, The bank ‘A’ grants a loan? What happens? It does not take out cash and give it to the borrower. It either allows the Borrower (X) to overdraw his account (if he has one with the bank) or it (Bank A) opens an account in his name to the extent of loan taken (Rs. 90), if he is a new customer. Let us say Bank ‘A’ grants a loan to X by opening an account in his favour.

The balance sheet of Bank ‘A’ will appear as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

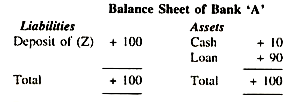

This is only a temporary phase because no one borrows from a bank merely to open an account or maintain it, one borrows to utilise the money. Let X who has borrowed Rs. 90 issues a cheque of Rs. 90 to R from whom he has purchased goods. Let R deposits the cheque in his account with bank ‘B’.

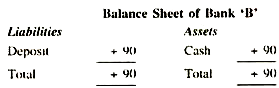

As such the balance sheet of Bank ‘A’ and ‘B’ will appear as follows:

Cash of Bank ‘B’ increases because it has collected from Bank ‘A’. The total deposits in the banking system now is Rs. 190. Bank ‘B’ further behaves in the same way as bank ‘A’ above, i.e., keeping 10% of the deposits in cash to meet the requirements of the depositors. He may further grant a loan of Rs. 81 of the borrower of Bank ‘B’ draws a cheque of Rs. 81 and thus cheque is deposited with Bank *C’, the cash of Bank ‘B’ will go down by Rs. 81 and that of Bank ‘C’ will go up by Rs. 81.

The balance sheets of Banks A, B, C, will appear as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, at each successive stage every bank which receives deposits from the previous bank will be able to lend 90% of the deposits—showing the process as follows:

100 + 90 + 81 + 72.90 +………

This is geometric series and the sum will be 100/0.10 = 1.000.

Thus, with an initial deposit of Rs. 100 the banking system has been able to create total credit of Rs. 1,000 i.e., ten times more than the original deposit. It is to be understood that it is not only the individual bank that creates credit many times the original deposit, but also the banking system as a whole can create derivative deposits up to several times the amount of an original addition to its cash holdings. Primary deposits, as we know arise from the actual deposits of cash in a bank.

However, the bank can create deposits actively by creating claims against itself in favour of a borrower or of a seller of securities or of property acquired by the bank. These actively created deposits are derivative deposits, which arise from loans or securities purchased or primary deposits created.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

An individual bank, when it creates derivative deposits, loses cash to other hanks; this transfer of cash within the banking system creates, in turn, primary deposits, enhancing the possibility for a further creation of derivative deposit, by the banks receiving the cash. This process of the commercial banking system to expand credit many times more the initial excess reserves is called the multiple credit creation. For example, let us suppose that Rs. 100 of excess reserve in Bank ‘A’ enable the creation of Rs. 100 of derivative deposits through the extension of loans to borrowers.

The borrowers make payments of Rs. 100 by cheques to customers of Bank ‘B’ resulting in a creation of Rs. 100 of primary deposits in Bank ‘B’. Assuming the customary cash reserve ratio to be 10%, the excess reserve of Bank ‘B’ and, therefore, the amount of derivative deposit is Rs. 90. Further, the payments of cheques by borrowers from Bank ‘B’ to customers of Bank ‘C’ create Rs. 90 of primary deposits in Bank ‘C’ and lead to excess reserves and derivative deposits of Rs. 81 in Bank ‘C’ etc. until the original Rs. 100 of excess reserves are diffused among many banks resulting in a multiple expansion of derivative deposits of Rs. 1,000 (Derivative deposits of Rs. 100 + 90 + 81 … + n = 1,000 or 10 times the original excess reserves of 100, given a 10% reserve ratio). Algebraically Rs. 100 + Rs. 100 (9/10) + Rs. 100 (9/10)2… + Rs. 100 (9/10)n. It is the sum of geometric progression a + ar + ar2… + arn , where, n = (n; tends to infinity or 1/1-r. In our example r = 9/10 or 90% and a = Rs. 100.

By substituting these values, we get:

Destruction of Bank Credit or Money:

Banks destroy credit as easily as they create it. Bank credit can be destroyed by means of a reduction in bank loans and investment. The extent of the destruction depends upon the prevailing cash reserve ratio. A reduction of cash below the reserves to support demand deposits leads to multiple contraction of bank credit throughout the banking system. Thus, in the previous example, the original reduction of Rs. 1,000 in Bank ‘A’, is followed by a reduction of deposits of Rs. 800 from Bank ‘B’, of Rs. 640 from Bank ‘C’ and so on.

The process of contraction of bank credit is the same as that of expansion—only in the reverse direction. The credit creation multiplier process works as easily in the backward direction. It may be mentioned that sometimes the government intervenes directly with the creation and destruction of money (by commercial banks). Under normal circumstances government need not interfere but in the overall interest of economic stability, to avoid both inflation or deflation, the government may create or destroy money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is in this sense that money is described as ‘a creature of the state’. The government may intervene by creating and destroying the legal tender, resorting to printing press, monetary management through treasury, demonetization, etc. Out of the various tools to create or destroy money, the choice of any particular tool will depend on the nature of the situation, objectives of monetary policy, monetary and banking convention, etc.

The Supply of Bank Deposits and Fractional Reserve System:

The traditional approach to the determination of the volume of bank deposits modified by an alternative approach. Bankers have always made out a case that they lend only the deposits they receive (or out of it). Thus, their ability to attract deposits is the chief constraint on their work. Economists, on the other hand, assert that bank lending itself creates deposits. Economists say bank deposits result or arise because of bank lending and not because lending is done because bank deposits are received. Bank deposits do not constitute a precondition for lending.

If a banking system works to a minimum ratio of reserves in this case cash to deposit liabilities— we say it is a fractional reserve system. Thus, so far fractional reserve system has been based on fixed cash reserve ratio. But this system is by no means confined to cash—this system could exist whenever banks maintain a fixed ratio of some asset or group of asset ‘reserves’—to other deposits liabilities— because a change in their holdings of the specified assets would be associated with a proportionate change in their deposits.

In other words, the new theory amounts to the fact that bank deposits bear a given relation to the bank reserves and a change in the reserve base (which includes cash plus assets of various types) will lead to a multiple change in bank deposits.

It is, therefore, essential to study the factors which determine the supply of reserves. If banks adhere to a fixed reserve ratio and if the supply of reserves is determined without any reference to the level of bank deposits, then it is reasonable to regard reserves as a proximate cause in the determination of bank deposits. But it the supply of reserves is determined by the level of bank deposits, rather than the other way round, we must look beyond reserves to some other explanation of changes in deposits.

Liquidity Ratio Theory:

The concept of multiple expansion of bank deposits is not restricted to the case in which the basis for expansion is a change in the banking system’s holding of cash. If it could be shown that the authorities controlled the supply of some other collections of assets held by the banks, and if the banks maintain a fixed proportion of these assets in their port-folios, then this particular collection of assets would form the base of a fractional reserve system and changes in the bank’s holdings of these assets would generate multiple changes in bank deposits (and hence the money supply). After 1950s it appeared that the collection of assets held as liquid assets by the London clearing banks filled this role.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, the theory of ‘liquid asset’ as basis of credit expansions has proved to be deficient in several respects, inasmuch as there are questions relating to the control of the liquid assets base—the extent to which such assets are held outside banks and the influences determining fluctuations in these holdings—the extent to which banks themselves can influence the supply of liquid assets. Further, the rigidity of the liquidity ratio has been questioned.

Do the banks really conform to a more or less fixed liquid assets ratio? Will a redistribution of deposits between the banks with high and with low liquidity ratios frustrate any attempt by the authorities to control bank lending by contracting the liquidity base ‘? Thus, we find that the liquidity ratio theory is defective or at best incomplete as an explanation of short-term changes in the level of bank deposits in the UK—at least it needs to be supplemented by a theory explaining the total amount of short-term government debt held by the private sector. This, however, does not mean that the theory could not be used to explain long-term trends in bank deposits.

Despite the shortcomings, the method of variations in reserve requirements relating them to the holdings of liquid assets (liquidity ratio approach) has definitely some advantages over the alternative device of fixing and varying the cash ratio. Like the cash ratio, the liquid assets ratio does not penalize the profit earning capacity of the banks. Newlyn, a monetary expert has strongly argued the case of a variable liquid assets ratio. Although the debate whether the variable liquid assets ratio is superior to the cash ratio as an effective means of credit control still continues ; it is, however, clear that in future the liquidity ratio theory may become more important in explaining movements in clearing bank deposits.

Further, the liquidity ratio theory breaks down because the changes in the liquid assets base of the banking sector as a whole will not cause the corresponding changes in bank deposits if they are accompanied by the changes in the distribution of deposits between banks which maintain low and banks which maintain high liquidity ratios. In conclusion, therefore, it may be said that the liquidity ratio theory of the determination of the volume of bank deposits in the UK is no more satisfactory than the cash ratio theory.

Government:

Government is another source through which significant variations or changes in money supply take place in a country. As the government have assumed many development and welfare functions—they bring about changes in money supply by various direct and indirect ways. Firstly, the government has the monopoly to issue money (notes and coins) and it has the power to destroy the same (sometimes suddenly, like demonetization of higher denomination notes) in extreme circumstances.

Similarly, the governments may and do resort to printing more money in times of financial needs. Such a method of bringing about changes in money supply is highly inflationary and should be resorted to sparingly. Secondly, the government may borrow from the Central Bank (out of its idle reserves) or from commercial banks (out of their time deposits).

The amount so borrowed soon finds a way out in circulation on account of the purchases made by the government of services and materials from individuals, firms or institutions. This brings, in turn, a net change (addition) to the supply of money. Thirdly, the budgetary operations of the government also have an impact on the money supply.

When there is a budget surplus showing an increase in the government deposits, there is a corresponding decline in the money supply. The government may hold this surplus (idle balances) continuously or it may use these balances to repay the outstanding debts. If the balances are held indefinitely, there will be net decrease in the money supply which may induce further secondary declines in the supply of money.

Similarly, in the second case the effects of-money supply will depend on whether the government pays back debts held by the central bank or debts held by the general public. Again, in case of a deficit the effect on money supply will depend on whether it is financed by a resort to the printing press or by borrowing from public or from the central bank. Except in the second case of borrowing from public, financing the deficit will make a net addition to the money supply.

Central Bank:

Central Bank is the most important institution and source of money supply because it has got the monopoly of issuing notes. The Central Bank can bring about variations in money supply by changing bank rate, by open market operations, by changing cash reserve ratios of commercial bank etc.