Money Creation by the Banking System:

The Money Multiplier and Bank Loans:

We now present an alternative way of describing the working of the money multiplier by showing how adjustments by banks and the public following an increase in the monetary base produce a multiple expansion of the money stock.

100-Percent-Reserve Banking:

In a world without banks, all money takes the form of currency. So the quantity of money is simply the amount of currency held by the public. Now suppose a bank is set up which accepts deposits from the public, keeps them safely but does not lend to the public.

The deposits that banks receive but do not lend out are known as reserves. Some reserves are held in the banks’ vaults but most are held at a central bank such as the RBI, since all deposits are held as reserves. So the money remains within the bank until the depositors withdraw a portion of it or write a cheque against the balance. The system is called 100- percent-reserve banking. The bank survives by charging deposits or a small fee to cover its costs. Since it is not making loans, it will not earn profit from its assets.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

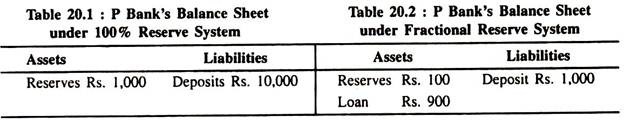

Suppose households deposit the economy’s entire Rs. 1,000 in the P bank (say, the Pioneer Bank). The bank’s assets and liabilities will both now be Rs. 1,000. So the money supply in the economy after the setting up of the bank is the Rs. 1,000 of demand deposits. A rupee deposited in a bank reduces currency by Re. 1 and raises deposits by Re. 1 — so the money supply remains the same. If banks hold 100% of deposits in reserves, the banking system cannot create credit.

Fractional Reserve Banking:

In general, banks create deposits on which no or low interest is paid, in order to make loans on which higher interest is earned. The deposits are created in the process of making the loans; a loan is credited to the borrowers’ account. Thus, the incentive to increase deposits lies in the possibility of making profitable loans.

When loan demand by potential borrowers falls off, banks may not create deposits up to the full limit that reserves would support. Thus, they may, from time to time, have on hand excess reserves. On the other hand, when loan demand is particularly strong, banks may borrow reserves at the discount window to support the additional deposit creation that accompanies the increase in loans. This degree of freedom that the banks enjoy to hold excess reserves or to borrow reserves makes the money supply responsive, to a certain extent, to the loan demand and the interest rate.

When loan demand is strong and interest rates are high, the banks will squeeze excess reserves and increase borrowing at the discount window, increasing the money supply supported by a given amount of un-borrowed reserves supplied by the central bank. Thus the money supply itself will have a positive elasticity with respect to the interest rate, reducing the slope of the LM curve — that is, flattening it. We may now briefly review the mechanism of money expansion in a fraction reserve system.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We know that the money supply consists of currency and demand deposits that are supplied by commercial banks. These banks have balance sheets made up of liabilities, including demand deposits and assets, including loans and reserves. The central bank requires that commercial banks retain a certain percentage of their liabilities as reserves.

Now suppose banks start to lend some of their deposits to the non-bank public — (households and business firms)—and charge interest on the loans. The banks must keep some reserves in their vaults 50 as to be able to meet the demand for withdrawal.

However, as long as the amount of new deposits approximately equals the amount of withdrawals, a bank need not keep all its deposits in reserve. This means that banks have an incentive to make loans. When they do this, we have fractional-reserve banking, a system under which banks keep only a fraction of their deposits in reserve.

Here is P bank’s bank balance sheet in 100% reserve system and fractional reserve system between and after it makes a loan.

Here the reserve-deposit ratio — the fraction of deposit kept in reserve — is 10%. This means that the P bank keeps Rs 100 of the Rs 1,000 in deposits in reserve and lends the remaining Rs 900. Now wee see that the P bank increases the supply of money by Rs. 900 by making a loan of this amount.

Before the loan is made, the money supply is Rs. 1,000, equating the deposits in P bank. After the loan is made, the money supply is Rs. 1,900: the depositor still has a demand deposit of Rs. 1,000, but the borrower now holds Rs. 900 in currency. Thus, in a system of fractional-reserve banking, banks create money.

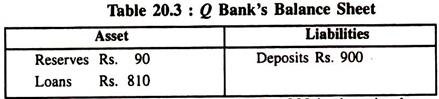

The process of money creation does not stop here. If the borrower deposits the Rs. 900 in another bank (or if the borrower uses the Rs. 900 to pay someone who then deposits it), the process of money creation continues.

The balance sheet of Q bank is:

It is quite obvious that Q bank requires the Rs. 900 in deposits, keeps 10%, or Rs. 90, in reserve and then loans out Rs. 810. Thus Q bank creates Rs. 810 as money.

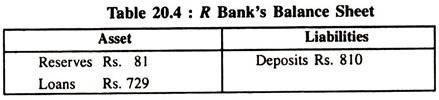

If this Rs. 810 is eventually deposited in R bank, this bank keeps 10%, or Rs. 81, in reserve and loans out Rs. 729, resulting in the following balance sheet:

The process goes on and on. And with each deposit and loan, more money is created.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

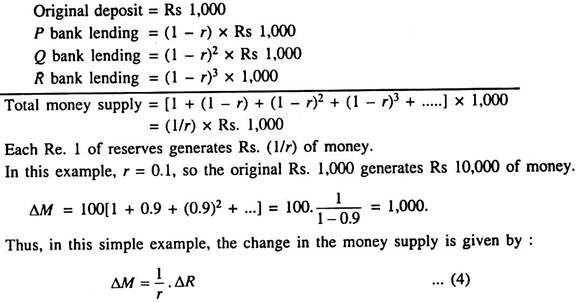

However, the above process of money creation cannot continue forever. So an infinite amount of money is not created in the economy. The whole process of money creation will continue for some time and will ultimately come to a halt when the last increase in deposit is not sufficient to generate a fresh loan.

Letting r denote the reserve-deposit ratio, the amount of money that the original Rs. 1,000 creates is:

where ΔR is the initial reserve increase and r is the reserve ratio. Here, 1/r is the bank (reserve) multiplier giving the effect of reserve changes on the money supply M.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The multiple increase in M occurs due the fact that each bank holds as reserves only a fraction r of its increased deposits, i.e., liabilities—and lends out (1 – r)% of the increased deposits. Thus, while each bank is simply lending out a fraction, 1 – r, of its increased deposit inflow, the banking system as a whole is increasing deposits by — times the reserves increase.

This example contains two important over-simplifications. First, since the banks stay loaned up, excess reserves do not enter the picture. This means that the money supply does not depend on the interest rate. Second, no provision is made for leakage into increased public holdings of currency which would reduce the value of the reserve multiplier. We now introduce some doses of realism in our analysis by incorporating these effects.

Financial Intermediation:

The main difference between banks and other financial intermediaries is the former’s ability to create money. Financial markets perform the important function of transferring the surplus reserves of some households which save some of its income for the future to those households and firms that wish to borrow to buy investment (capital) goods to be used for future production.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The process of transferring funds from savers to borrowers goes by the name financial intermediation. Of all the financial intermediaries, including the stock market, the bond market, and investment companies and the mutual funds, only banks have the legal authority to create assets that are part of the money supply, such as deposits withdrawable by cheques. This means that banks are only financial institutions that directly influence the money supply.

Money Creation vs Wealth Creation:

No doubt the system of fractional-reserve banking creates money. But it does not create wealth. When a bank lends a portion of its excess reserves, it gives borrowers the ability to make transactions and, therefore, adds to the country’s money supply. Since the borrowers are also undertaking a debt obligation to the bank, however, the loan does not make them wealthier. This simply means that the creation of money by the banking system increases the economy’s liquidity, not its wealth.

Determinants of Total Bank Credit:

There are various determinants of the amount of total credit that can be created by the banking system.

These are:

1. Excess reserves:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The credit-creating capacity of banks depends on the total amount of excess reserve being held by the banking system as a whole per period. The amount of deposit created varies directly with the amount of excess reserve.

2. Reserve ratio:

The maximum amount of credit which can be created by the banks also depends on the reserve ratio maintained by the banking system as a whole. If the central bank raises the minimum-reserve ratio, then the amount of deposit created by the banking system as a whole will fall. The converse is also true.

3. Banking habits of the people:

The credit creating capacity of the commercial banks also depends on the banking habits of the people. In industrially advanced countries the banking habits of the people are well- developed and most of the transactions are settled through cheques. Obviously, the credit creating capacity of the commercial banks are higher in such countries.

In developing countries like India just the opposite is true. Banking facilities are not available in most rural areas where 70% of the people live. Moreover, banking habits are not well-developed in such countries. In fact, the prevalence of the barter system and lack of monetisation in most developing countries of Asia, Latin America and Africa obstruct multiple credit expansion by the banking system

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. Availability of collateral securities:

Banks normally demand securities for giving loans. If the borrowers do not have sufficient acceptable securities to offer then the total amount of deposits created by the banking system will be low. Even if banks are eager to lend, they cannot expand their volume of loan.

5. Existing business conditions:

The amount of credit which can be created by the banking system as a whole depends on the state of the economy or, to be more specific, on existing business conditions. If the economy is expanding, there will be more demand for goods and services. As a result profit prospects will be bright.

So business people will be eager to produce more because they can sell more. Hence they will take more loans and the demand for bank loan will increase. This will make it profitable for the banks to expand the volume of credit. In contrast, if the economy is in depression banks cannot create much credit. It is because there will not be much demand for bank loan in such times.

6. Expansion of the banking system:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The total amount of credit which can be created by the banks depends on the expansion of the country’s banking system. If the banking system is well-developed and if there are many banks in the country, the credit-creating capacity of banks will be high. It is because the total amount of credit that can be created by the banking system as a whole is a multiple of the total excess reserves of the banking system. But a single (monopoly) bank in the system cannot create credit (deposit) exceeding its own excess reserve.

7. Legal reserves:

If the legal reserve is 10%-but commercial banks keep 20% reserve, the deposit (credit) multiplier will be 5 and not 10. Thus if there is an initial increase in cash deposit of a bank of, say, Rs. 1,000, the total increase in bank deposit at the end will be only Rs. 5,000 and not Rs. 10,000. This is what happens in countries like India having underdeveloped money markets.

8. Cash leakage:

If depositors withdraw a certain amount of money for spending (transactions) purposes, banks will be left with less cash. Thus, if people’s transaction demand for money increases, the amount of cash with the non-bank public will also increase. This will reduce the credit- creating capacity of commercial banks.

In short, the capacity of commercial banks- to create credit depends not only on their own cash requirements but also on the cash requirement of the public or of the non-banking system. Their own cash requirement depends mainly on the monetary (credit) policy of the central bank. The central bank often limits money supply growth in order to slow down the economy and control inflation. But the cash requirement of the public depends on transactions demand for money, i.e., the amount of money people demand for spending purposes.