Read this article to learn about the approaches and theories of demand for money in an economy.

Introduction:

The total supply of money with the public, as we have seen is largely determined by the currency authority and banking system.

It is the demand for money that presents numerous difficulties because the demand for money has been interpreted in different ways. The demand for money as a medium of exchange need not be confused with a demand for money income.

The classical and the neoclassical monetary theory, as we have learnt regarded money simply as a convenient device for facilitating transactions in goods and services. Thus, according to them the demand for money is not the demand for its own sake but the demand for money to spend. Two important theoretical explanations of the demand for money include the classical quantity theory and the Keynesian theory revolving around the demand for money for transactions and the demand for money as an asset.

Keynesian and Classical Approaches:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Keynes had developed the ‘store of value’ function of the demand for money. The demand for money became the demand for holding cash balances depending upon various liquidity motives. Money is not merely spent but is preserved as a form of wealth or assets which can be easily converted into cash or any other form of wealth at any lime. According to Keynes, the various liquidity motives are transactions, precautionary and speculative on account of which money is demanded. Keynesian theory left the demand for money in a rather unsatisfactory state.

His theory of the demand for money (M1 + M2) proved to be rather an awkward hybrid of two theoretically inconsistent approaches, with the transactions demand being regarded as technologically determined by the traditions and customs of society and the assets demand being treated as a matter of economic choice.

The fundamental difference between quantity theorists and the Keynesian approach is—what constitutes an effective substitute for money balances. Keynesians contend that only close substitute for money is alternate financial assets, implying that with the increase in the volume of money, a purchase of financial assets will occur leading to a fall in interest rates.

A fall in interest rate renders money holdings more attractive and other financial assets less attractive until a new equilibrium is reached between the actual money stock and desired holdings. In other words, the implication is that changes in money supply will lead to variations in demand for money and its velocity. The Keynesian position is that consequences of this on investment and consumption would be at least limited, because the investment spending is often interest-inelastic and the wealth effect of a fall in interest rate is a minor factor in the consumption function.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On the other hand, the quantity theorists maintain that the only plausible substitute for excessive money supply was goods and services (money being demanded as a medium of exchange)—there was no role of financial assets in their approach. Hence, an increase in monetary stock will increase expenditure on commodities and raise their prices. Implicit in this approach was the fact that the demand for money was stable and its velocity comparatively constant— the only demand for money was the normal transactions demand.

Monetary economists in recent years have refined and elaborated Keynes’ theory of the demand for money. His emphasis on the speculative demand for money has been gradually abandoned and reabsorbed into the general theory of asset holding. The recent tendency has been to give up the mechanistic treatment of demand for money as equal to M1 + M2 on the grounds the public does not hold just two stocks of money (M1 + M2).

Money’s use in transactions is not the only factor from which a demand for money may arise, its predictable market value can make it a desirable asset to hold. One earns no income from holding money so that other assets are normally or preferable way of holding wealth. From time to time, expectations about future fluctuations in the prices of income earning assets may lead wealth-holders to believe that to own them will lead to capital losses.

The zero gain from holding money at such limes is clearly preferable to a loss from holding other assets, so that, quite apart from its use in transactions, money becomes something desirable to hold. Analysis of this type of behaviour is also quite prominent in theorizing about the demand for money. Baumol C1952) and Tobin (1958) have developed a formal analysis of transactions demand on inventory basis.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Both make use of the theory of inventory holding to the transactions demand for money. Another trend has been to develop a capital-theory approach to the transactions demand for money. Thus, at one extreme we have the “purists’ who maintain that money is only that which can be used for immediately making payment, that is, money is only currency plus bank deposits withdrawal by cheques. Others maintain that money is anything that serves the function of money in the sense of being an asset whose capital value is safe and they will include in money time deposits, saving deposits or even farfetched items such as borrowing power on life insurance policies.

Although we approach the demand for money by looking at three motives for holding it we cannot separate a particular person’s money holdings into three neat distinct categories and say that so much is being held for each separate motive. Money being held to satisfy one motive is always available for another use. Money is costly to hold. The more of it an individual holds, the more interest is lost.

Once we understand interest as the cost of holding money, it becomes natural to expect the demand for money to fall when the interest rate (cost of holding money) rises. In the transactions demand we are concerned with a tradeoff between the amount of interest an individual foregoes by holding money and the costs and inconveniences of holding a small amount of money. The smaller the amount of money held on average, the more costs the individual incurs to manage his holdings of cash and saving deposits.

The modern approaches to the demand for money question the usefulness of maintaining the distinction between the various motives for holding money and the distinction between the transaction demand and the asset demand for cash as separate components in the total demand for money holding. Hence, the analysis of the demand for money outlined below known as an inventory—theoretic approach, has been developed.

Baumol Model of Money Demand (Inventory Approach):

The inventory theoretic approach to the demand for money is associated with the names of W. Baumol (1952) and J. Tobin (1958), each of whom used it to study the demand for money. The most famous result of Baumol and Tobin is the square-root law of the demand for money. Originally, the approach was developed to determine the inventories of goods a firm should have on hand. The analogy between money as an inventory of purchasing power, standing ready to buy goods, and an inventory of goods, standing ready to be bought by customers, is quite close.

Prof. Baumol’s analysis takes into consideration the transactions demand for money, which in turn, is determined by general level of economic activity (income). Baumol approaches the matter as a problem in inventory management the inventory being the stock of money the individual or business firms decide to keep for transactions. Since the receipt of income of an individual or business firm does not coincide exactly with expenditures, these must be an inventory of cash on hand. We know that it always costs something to hold inventory of any type, including an inventory of money.

The firms and individuals always try to minimize the cost of holding money for transaction purposes. These costs are called opportunity costs and withdrawal costs. The opportunity cost is represented by the current rate of interest (i). This cost exists because cash held idle foregoes the opportunity to earn an income (through lending at the current rate).

The larger the inventory of cash held for this purpose the greater will be the cost. But these are withdrawal costs which occur each time an income earning asset is converted into cash. These are broker’s fees, postages, telephone bills, book-keeping, clerical expenses etc. (or any other non-interest cost which may be incurred on account of conversion of asset into cash). The more frequently, the conversion transactions to obtain cash are undertaken, the greater will be this type of cost. Thus, total cost for the inventory of cash held for the transactions motive is the sum of interest (opportunity) and transactions (withdrawals) costs.

It is, therefore, clear if the firms or individuals hold large cash balances, there will be few withdrawals to acquire more cash and therefore transactions costs will be small but the opportunity cost of the interest foregone will be large on the other hand, if attempts are made to reduce the opportunity cost by holding down the size of cash inventory—this may necessitate more frequent withdrawals, raising in turn, transactions part of total inventory cost. The problem of transactions demand for money is, then, the problem of determining the optimal amount of cash the individual will hold. In other words, this can be seen as problem of minimizing the total cost of financing transactions.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In order to solve this problem of optimum balances of money to be held at minimum total cost. Baumol evolved a formula to determine the size of cash withdrawals (conversion of bonds to money) which would minimize the total cost of keeping an inventory of optimal cash balances large enough to meet transactions demand. The formula is C = 2bT/i; where C is the optimum withdrawal of cash, T is the total transactions in the period ; b the costs associated with conversion of earning-assets into cash, and i the appropriate market rate of interest. Essentially, the formula shows that the demand for cash balances for transactions purposes will vary positively with the volume of transactions and transaction costs, but inversely with the opportunity costs (the rate of interest—i).

The formula also shows that these are economies of scale in the use of money. The meaning of this is that the richer or more prosperous an individual or business firm is, the greater is their ability to economize, in the use of cash. The formula shows that the optimum level of transactions cash increases with the total value of expenditures to be made during the period. But it has been found to be a function of the square root (see further) of total expenditure, implying strong economies of scale in an individual’s transactions demand for cash.

This is the most important result of Baumol Tobin Model of demand for money and is, different from the neo-classical and even Keynes’ theory which hypothesizes the transactions demand for money to be a proportional function of income (or expenditures). This model (Baumol-Tobin) further shows that the optimum level of transactions cash varies inversely with the level of transactions cost.

A rational individual will prefer to transfer his income receipt into an interest yielding asset and then successively transfer portions of the asset back into the cash to fulfill his transactions needs. Since a cost in the form of the interest foregone for holding cash is to be given, hence the incentive to minimise cash holding. However, as we have seen above, there are costs associated with liquidation of the assets. Hence, a rational individual is faced with the problem of—how to allocate one’s assets between cash and interest yielding bonds.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

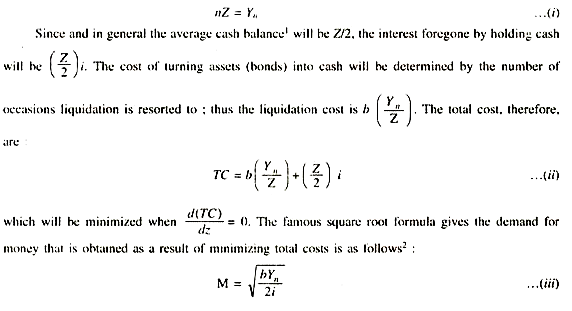

More formally, according to Baumol, if Yn is the income receipt, i the rate of interest, b the cost of turning bonds into cash and Z the value of the bonds turned into cash to meet successive transactions needs, the question confronting the utility maximize is how to determine the size of Z i.e., the cash holding per transactions period and further n stands for the number of withdrawals or the number of times the individual adds to his cash balance during the month. If the persons make n equal sized withdrawals, then the size of each transfer (Z) is Yn/n. For example, if Yn is Rs. 900 and n, the number of transactions is 3, then Z, the amount transferred in cash each time is Rs. 300.

As such we can rewrite:

Tobin Model of Money Demand (Portfolio Balance or Asset Choice Theories):

The Keynesian asset demand for cash (M2) rests on the assumption that individuals have or possess a concept of a normal or expected rate of interest. If the existing market rate of interest is in excess of the normal rate, the expectation is that market rates will fall or alternatively that bond prices will rise.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

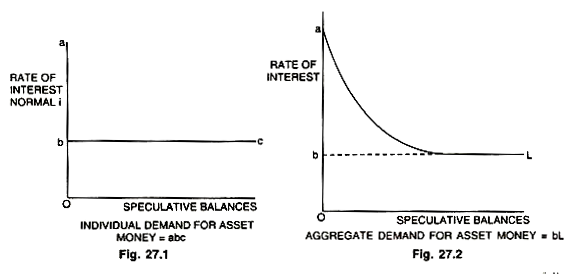

Under these circumstances, all asset cash would be turned into the purchase of bonds ill the anticipation of making a capital gain and consequently the individual’s asset demand for cash would be zero. On the other hand, if the existing market rates lie below that expected, the individual will have a zero demand for bonds and infinite demand for asset cash. The logic of the Keynesian approach, therefore, is that the individual holds either asset, cash or bonds but not both simultaneously. His speculative demand for money is summarized given in the Fig. 27.1.

However, the conventional Keynesian aggregate demand curve for asset money holding shown in the Fig. 27.2 is accordingly derived from the assumption that different individuals possess different expectations about the normal rate between the points a and b.

Professor Tobin utilizes the concept of risk to explain the division of individual’s asset portfolio between bonds and cash and again; why liquidity preference function (the asset demand) is negatively sloped. Although Tobin’s and Keynes’ conclusions tally regarding the shape of L.P. function yet their approaches differ ; Tobin explains this phenomenon in terms of attitude towards risk ; while Keynes explains it in terms of expectations with respect to future bond prices.

Tobin’s analysis does not depend like Keynes on the notion of normal rate of interest to understand why people choose to hold money rather than bonds (and vice versa) because in time (or as the time passes) the current rate of interest (assuming it to be reasonably stable)—may come to be regarded as normal, if it is so, then a key motive for holding assets in money form disappears. Tobin’s analysis based on risk attitude shows that the asset demand for money will still be inversely related to the rate of interest (even if the concept of normal rate of interest is ignored).

According to Tobin there are Iwo types of wealth holders—risk takers and risk averters because whenever a person holds bonds in preference to cash, he incurs the risk of capital loss or gain on account of uncertain knowledge of future bond prices. The larger the proportion of assets held in bonds the greater the risk. The risk lovers or risk takers according to Tobin need not be induced by higher interest rates to hold bonds—they are likely to maximize both risk and interest income by holding all their assets in bonds.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But in actual practice, it has been seen, more people are risk averters than risk lovers. The risk averter will keep more diversified asset holding—assuming more risk (holding greater ratio of bonds)—only as the rate of interest increases (higher interest rates are necessary to compensate for additional risk in keeping more bonds and less cash). Apart from Tobin’s stress on risk attitude, both attitude, towards risk and expectations matter in actual practice to determine the asset demand for money.

Tobin’s contribution lies in reformulating the Keynesian demand for assets money which asserts that potential bond holders are uncertain about future interest rates and this uncertainty leads to investment in long dated bonds involving the risk of capital gain or loss. The potential investor, therefore, must weigh the elements of risk against the expected return from his investment.

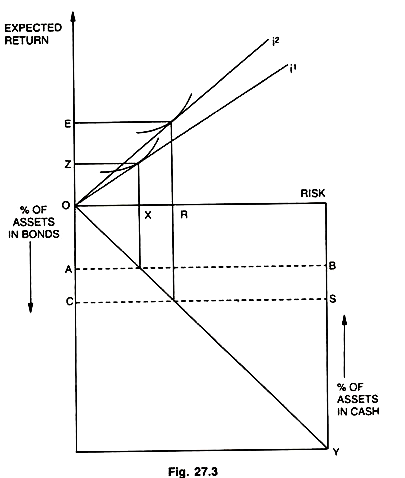

Optimal decision-making requires the help of conventional indifference curve analysis and suggests that normally the individual will hold both bonds and speculative balances. The argument is illustrated in the Fig. 27.3.

The lower portion of the figure shows the allocation of total asset between idle cash holdings and bonds ; while the upper part shows the tradeoff between risk measured on the horizontal axis and expected return, measured on the vertical axis (the expected return includes the expectation of a capital gain or loss) assuming the initial interest rate i1—the optimal combination will be OX of risk combined with OZ of expected return, showing an investment of OA in bonds and retention of YB in cash.

Supposing the interest rate increases to i2—raising the expected return associated with any degree of risk. A rise in the interest rate will incorporate an income effect, allowing the investor to take less risk, while also producing a substitution effect, in favour of more risk because the cost of holding idle balances has increased.

If substitution effect is stronger as shown in the Fig. 27.3, the investor will increase his risk and reduce his holdings of asset cash. The degree of risk increases to OR and the expected return becomes OE investment in bonds is shown as OC and speculative money balances fall to YS. All that is needed to obtain the Keynesian result of an inverse relationship between the asset demand for money and the rate of interest is the assumption that the substitution effect outweighs the income effect in an analysis that admits of the simultaneous holdings of both cash and bonds.

This analysis of the demand for money shows that the real demand for money will vary inversely with the rate of interest and positively with the level of output. Does the demand for money actually behave in this fashion? Since Keynes’ General Theory there has been large number of empirical studies and investigations into the demand for money relationship.

No study or investigation has yet been able to come up with an exact statement of this relationship—one that could be used without question for policy or predictive purposes. The inventory theoretic approach enunciated in the Baumol- Tobin Model is to show that an individual will hold a stock of real balances that varies inversely with the interest rate but increases with the level of real income and the cost of transactions. The income elasticity of money demand being less than unity gives—what are called economies of scale.

The logic of Baumol’s model leads to the assertion that the transactions demand for cash will respond, inversely, to changes in interest rates thus reinforcing, ceteris paribus, the interest elasticity of the total demand for cash holdings.’

It may be pointed out that, in practice, the above results concerning the arrangement of transactions cash on inventory basis may be important for large firms and organizations and not for small economic units. Baumol-Tobin model also assumes that micro-results for an individual cash-holder will also equally well apply at the macro-level. This may not happen if we take into consideration differences in cash management behaviour of individual units. But most of the studies done or appeared to confirm in general theoretical statements made about the demand for money.

The main conclusions and empirical findings on demand for money, so far, may be summed up as follows:

(a) The demand for money balances is a demand for real balances—that is, the demand for nominal balances rises in proportion to changes in the price level. In other words, people don’t suffer from money illusion, they will adjust their nominal holdings of money whenever the price level changes upwards.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) The demand for real money balances responds positively to changes in real income.

(c) The demand for real money balances is related negatively (inversely) to changes in rate of interest, meaning that, when interest rates rise, less money will be held and when they fall, more money will be held.

(d) Evidence is also there that the demand for money is influenced by changes in expected rate of inflation. If the inflation rate is expected to go up ; this will reduce the demand for real money balances, because the higher rate reduces the real value of an individual’s nominal money holdings.

The Demand for Money—Post-Keynesian Modifications—(Tobin, Turvey, Meitzer, Patinkin, Friedman):

Neo-Keynesian theories of the demand for money, strongly influenced by Tobin and his associates have also taken issue with Keynes treatment of the demand for money on the ground that it is stated with reference to only one interest rate—that pertaining to long-term government bonds. In their approach (Tobin and others) money is but one asset. In the entire spectrum of assets possessing varying rates of return, and the demand for money (indeed for any asset), can be approached only in terms of its rate of return in relation to all other prevailing rates of return.

In other words, in terms of changes in the structure of interest rates. The asset choice (portfolio balance) approach focuses attention not on the volume of money or the movement in the long-term interest rate as being the significant variable, in contrast to the Monetarist and Keynesian viewpoints respectively, but rather stresses changes in the structure of interest rates. Moreover, while the Monetarists and Keynesians normally agree that an increase in money stock will lead to a rise in nominal GNP (the former directly, the latter through the interest rate effect), the asset choice theory implies that an increase in the money stock could be contractionary and vice versa.

Keynes gave a limited, interpretation to transactions demand for money. This concept has been elaborated by James Tobin, W. Baumol and R. Turvey. Baumol’s analysis (1952) is very interesting and shows how transactions demand can be treated as a problem of capital theory i.e., it treats demand as working capital or inventory of money stock and that the demand so derived varies inversely with the rate of interest and is subject to economies of scale.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Tobin (1958) has provided a model which predicts that the proportion of each individual’s assets held as money may vary with the rate of interest. Integration of all the three motives for holding or demanding money is perhaps the most important development in the theory of demand for money. Modern economists reject the idea that the demand for transaction balances bears the simple, proportional relationship to the level of transactions in the economy. They treat money holdings as a kind of inventory and the size of this inventory of money held for transactions purposes will be smaller, when the rate of interest is higher and vice versa.

Modern economists having removed rather an awkward classification of two or three theoretically and inconsistent approaches (with Lt being regarded as technologically determined and La or Ls being treated as a matter of choice) treat the demand for money as a whole being determined by the level of income and the rate of interest. Hence, the dichotomy of the demand for money in Keynes’ liquidity preference theory stands abolished because there are not actually two different stocks of money as made out by Keynes but a single unified stock of money which is held for all purposes.

Thus, it is said that there has been since then (1958) important developments in this area of the view that there are not only two types of assets—money and bonds—-as assumed by Keynes, but rather a diversity of assets with different maturities. In Keynes’ two asset model the only alternative for the holding of bond is the holding of money. But this is not very realistic.

The choice according to modern economists lies no more between holding money and bond but between different types of assets of different maturity and earning capacity, where money is the most liquid form of asset—and this in turn, has led to the evolution of general theory of price formulation of assets and also to the integration of the theory of money with the theory of capital. This approach is associated with the name of James Tobin, who by his portfolio balance theory, tried to give a general theory of asset holding which meant that the monetary policy can ultimately through a series of substitution of assets for securities or money, influence the investment decisions.

Where the new approach differs from the Keynesian approach is the formulation of demand for money as a form of capital or wealth relating the demand for money to total wealth, which comprises of all sources of income. Thus, according to Tobin individuals, firms and institutions are always busy in building up portfolio of assets, in which money, short-term securities, long-term bonds and physical assets of various kinds, all find a place. As such the wealth holder starts behaving like a bank-striking a balance between liquidity and profitability.

Wealth holders ensure that they have sufficient assets that may be less liquid but more profitable to balance the assets which may be less profitable and more liquid. The most important development in this respect is perhaps an insistence on the fact that wealth holders, banks, companies and other institutions—who have to sell because they fear a rise in the rate of interest, will, not actually switch on their assets into cash—but they will switch on from long-term bonds to short-term securities.

Recent empirical work in financial analysis has centred with a few exceptions on estimating the demand for money. Although there is little agreement on the suitable definition of monetary assets, yet a general consensus seems to have been reached that the dependent variable is the stock of monetary assets, however, defined, and that the determinants of quantity demanded are own-price of substitutes and a wealth or income variable. The Keynesian system accorded the financial relationship central role, even though Keynes himself was highly skeptical of the empirical responsiveness to consumption, saving and investment decisions to money stock variations. In response to Neo-Classical critics.

Neo-Keynesians introduced real wealth as a variable affecting spending and production behaviour, resulting in the recognition that portfolio composition, as well as the total value of wealth stocks, play crucial role in influencing asset owner behaviour on current account.

Moreover, developments along Portfolio Balance Theory of Tobin differentiated short-term securities from long-term securities and introduced the speculative motive for holding short-term securities instead of bonds as distinguished from the Keynesian speculative motive for holding money instead of bonds.

The Keynesian analysis of elasticity of the demand for money instead of being tied to demand for money alone is now being applied to the demand for liquid assets in general; as a result, a general theory to assets holdings has emerged in which the rates of return on assets are the prime determinants of the quantities of these assets that people wish to hold called—a ‘portfolio balance’ theory; which grew out of the effort to work out the theory of money in terms of the theory of capital.

Tobin’s transmission mechanism is based on the belief that all the assets can be arranged along a spectrum of liquidity. One can assume that all important effects will occur through substitution between an asset and its neighbour on the liquidity ladder. Further, each substitution will cause or be caused by a change in the relative price of assets, that is, interest rates and asset prices generally.

The implications of this type of Tobin’s mechanism are:

(a) Any influence of a change in monetary policy will be slow acting, indirect and unpredictable—but nevertheless present,

(b) It is desirable to make the primary policy target of ‘monetary policy’ an asset or price close to real assets (e.g., equities or bonds);

(c) One can observe a price rather than a quantity—i.e. long-term interest rates should be the main indicator of policy. It is worth noting that the Tobin’s Model is very similar in spirit to the Radcliffe Committee’s approach.

R. Turvey. The current tendency is to move towards a generalized theory of asset holding in order to take account of more alternatives than the simple bond cash choice assumed by Keynes. It is the most important modification and extension of the liquidity preference theory. In this connection Turvey’s theory of asset price formation becomes important. Consider money, bonds and real assets as the alternatives for holding money as an asset.

In general, suppose that:

(i) If wealth increases, given constant relative prices, the demand for all assets will increase, and

(ii) Given total wealth, a fall in relative prices of any one asset will increase the demand for it, so that :

W = M + NH + RO: where, M is the quantity of money, N the number of bonds, H its price (inverse of rate of interest), R the income deriving from the ownership of real assets and O the value of a right to a rupee per annum of such income and W the wealth of private sector. Thus, given the Y. they are functions of three variables, M. N, R. If attention is concentrated upon each one in turn on a ceteris-paribus basis, it might be said that we have a liquidity preference theory; a bond preference theory and a. portfolio or real asset preference theory respectively of the demand for money, the price of bonds and of income from real assets.

Again, a great deal of attention has also been given to the relation between the demand for money and the rate of interest with the object of discovering if a stable of relationship exists at all and if so, how sensitive the demand for money is to changes in interest rates. The main empirical studies in this respect have been made by M. Friedman, A. Meltzer and H.A. Latane.

Friedman, making use of his permanent income hypothesis derived an interest-inelastic demand function for money. Latane developed a demand function for money which shows that the ratio of money to income is a function of the long-term interest rate. The question of interest elasticity or interest inelasticity is of great importance in monetary theory and monetary policy.

The assumption of interest-elasticity of the demand for money establishes the importance of the classical quantity theory of money (with constant velocity) and also proves the efficacy of monetary policy for promoting full employment. It is also significant to explain Keynesian liquidity trap.

In Meltzer’s work, there is an effort to relate the demand for money to total wealth rather than income alone. He also found that the demand function for money is highly interest-elastic. His work emphasized that wealth (besides income) is a factor determining the size of the demand for money.

It has interesting implications because the value of individual and collective wealth depends, in turn, on the rate of interest. The lower the rate of interest—the greater the capital value of bonds. It applies to other assets also. Since the capital value of any asset is the discounted value of its future earnings, lower rate of interest increases the value of all capital assets, thereby raising the total wealth and vice versa.

The choice of interest rate is dictated partly by the availability of suitable statistics and partly by the investigator’s theoretical approach. The Keynesians might naturally employ a long-term rate of interest (such as the yield on 20-year bonds in the US or yield on consoles in the UK) because this is central to the liquidity preference theory. However, in the light of the theoretical work on the relation between the transactions demand and interest rates, he would also be entitled to choose a short-term rate of interest (on commercial bills in the US or treasury bills in UK).

The quantity theorists might select a long-term rate following Friedman’s theoretical approach or a short rate because the key interest rates of explaining the demand for money are likely to be those on the closest substitutes. Since the theory gives no clear cut answer on the choice of interest rates, empirical and research studies, therefore, usually try to employ a variety of interest rates and see which contributes most to the explanation of the demand for money and the rate of interest. Since changes in the interest rates are by no means unusual within a period of business cycle, it can be seen that interest rates have a considerable influence on the demand for money.

Don Patinkin. Keynes based his analysis on the assumption of a given price level. It meant that he ignored the effects of price changes on the demand for money. Don Patinkin, Conard and others have made attempts to incorporate the effects of price level changes on the liquidity and the demand for money. Patinkin has shown that all the motives transaction, precautionary as well as speculative are affected by the changes in the price level.

His argument is that given perfect wage and price flexibility and absence of money illusion, let the quantity of money be doubled in the market. This, in turn, would increase the demand for money on speculative account (M2) because of the positive real balance effect. In other words, an increase in the quantity of money would raise the price level proportionately at the invariance (un-alterability) of the rate of interest. And even if there is change in the rate of interest it will be a short period phenomenon. Thus, Patinkin’s contribution lies in modifying Keynes theory of liquidity preference or the demand for money on the ground of ignoring the changes in price level.