Read this article to learn about the supply of money in an economy and its components.

Supply of Money:

Money supply means the total amount of money in an economy. The effective money supply consists mostly of currency and demand deposits.

Currency includes all coins and paper money issued by the government and the banks. Bank deposits (payable on demand) are regarded part of money supply and they constitute about 75 to 80 per cent of the total money supply in the US. Some economists also include near money, or such liquid assets as savings, deposits and government bills in the money supply. The total supply of money is determined by banks, the Federal Reserve, businessmen, the government and consumers.

For theoretical purposes money is defined as any asset which performs the functions of money—but in actual practice, there are many financial assets which perform these functions to a greater or lesser degree and this makes it difficult to measure empirically the magnitude of money. It should be noted that ‘money supply’ which refers to the total stock of domestic means of payment owned by the ‘public’ in a country, we consider the stock of money in spendable form only to be the main source of money supply.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In other words, the cash balances held by the central and state governments with the Central Bank and in treasuries are generally excluded on the ground that they arise out of the non-commercial, particularly administrative operations of the government. Thus, the ‘quantity of money’ means the ‘total amount of money in circulation’ in existence at a time.

Money is something which is measurable. Supply of money refers to its stock at any point of time, it is because money is a stock variable as against a flow variable (real income). It is the change in the stock of money during a period (say a year), which is a flow. The stock of money always refers to the stock of money held by the public. Throughout history the question of not only what constitutes money but where it comes from has been both important and controversial.

In contrast to income, which is measured over time; the money is a stock, not a flow. Since money is a stock, it means that the amount of money in existence at any point of time must be held by some entity in the economy. Economists make a distinction between amount of money in existence at any point of time and the amount that people and institutions may want to hold for various reasons. When the amount of money actually being held coincides with the amount of money individuals, business houses and governments actually want to hold; a condition of monetary equilibrium exists.

A distinction must be made between the current deposits or current accounts of banks which have the status of money and deposit accounts (fixed or savings deposits) which do not have the status of money and are at best regarded quasi-money or near money. The reason being that time deposits of commercial banks can be drawn only at the end of a fixed period or earlier by paying a penalty or by obtaining prior permission. These are no doubt a store of value but are not the means of payment but only equivalent to means of payment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These are no doubt liquid assets but they are not so liquid enough as to rank as money. What distinguishes these deposits is the fact that they earn an interest income and can be converted as means of payment only after some delay and not at once. As such, these time and saving deposits are excluded from the pool of the money supply.

However, alternative definitions of money have been adopted by many writers. Notably, the Chicago School led by Milton Friedman opts to include all bank deposits, time and demand, in money supply. In fact, Schwartz and Friedman are willing to consider as money all marketable government securities which are supported at par. By the same logic, there is no reason why the liabilities of saving institutions should not also be included in money.

The debatable question is whether the measure of money should be extended to include other deposits liabilities of the commercial banks, e.g., time deposits in USA and deposit accounts in the UK. Some investigators go further and include the liabilities of some other deposit taking institutions, such as savings and loan associations in the USA and saving banks in Britain, on the grounds that their fixed monetary value—and usually the ease of encashment—makes them good substitutes for interest bearing bank deposits.

It has, therefore, to be observed that various measures of money supply keep on changing from country to country and from time to time within the country. As such, the measurement of money supply becomes an empirical matter. Up to 1968, the RBI published a single measure of money supply (called M and later on M1) defined as currency and demand deposits (dd), held by the public. It was called the narrow measure of money supply. After 1968 the RBI started publishing a ‘broader’ measure of money supply called aggregate monetary resources (AMR) defined as M or M1 plus the net time deposits of banks held by the public (M3).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, since 1977 RBI is publishing data on four alternative measures of money supply denoted by M1, M2, M3 and M4 as follows:

M or M1 = c + dd + od

M2 = M1 + Savings deposits with post office saving banks

(AMR) M3 = M1 + net time deposits of banks

M4 = M3 + total deposits with post office saving banks.

where c stands for currency held by public; dd, net demand deposits of banks; od implies other deposits of the RBI. Currency includes paper currency and coins, that is notes issued by the RBI and one rupee and other small coins issued by the Government of India.

Net demand deposits include deposits held by public and not inter-bank deposits—deposits held by one bank for another. These are not held by public hence excluded. Other deposits (od) of the RBI are its deposits other than those held by the government (Central and State Governments), banks, and a few others. These other deposits constitute very small proportion (less than one per cent) of the total money supply, hence could be ignored.

Each definition of money supply from M1 to M4 has its adherents; but by and large most economists prefer the most common sense and most acceptable definition of money or money supply, that is, M1—because it includes everything that is generally acceptable as a means of payment but no more. Once you go beyond currency and demand deposits, it is hard to find a logical place to stop, since many things (bonds, stocks, debt instruments) contain liquidity in varying degree. It is better, therefore, to stick to M1 definition of money supply including currency plus all demand deposits.

High powered money and measurement of money supply:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It should be noted that money supply is not always policy determined. In fact, money supply is determined jointly by monetary authority, banks and the public. It is true that the role of monetary authority is predominant in determining the supply of money.

Two types of money must be distinguished:

(i) Ordinary money (M) and

(ii) High powered money (H).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Ordinary money (M) as we have known is currency plus demand deposits: M = C + dd. On the other hand, high powered money (H) is the money produced by the RBI and the government of India (small coins including one rupee notes) held by the public and banks.

The RBI calls it H ‘reserve money’. H is the sum of:

(i) Currency held by public (c);

(ii) Cash reserves of the banks (R) ; and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) Other deposits of RBI (od), we can ignore item (iii) from theoretical discussion as it hardly constitutes one per cent of total H. Hence, H = C + R. Now, if we compare the two equations of two types of money ordinary money (M – C + dd) and high powered money (H = C + R), we find C is common to both ; the difference between the two M and H is due to dd in M and R in H. This difference is of vital importance. Banks are producers of demand deposits (dd) and these demand deposits are treated as money at par with currency (c).

But to be able to create (or produce) dd; banks have to maintain R, which in turn, is a part of H, produced only by monetary authority and not by banks. We know in a fractional reserve banking system, dd are a certain multiple of R, which are a component of H; it gives H the quality of high powered-ness (high powered money as compared to M)—the power of serving as the base for multiple creation of dd. That is why, H is also called “base money’. H thus becomes the single most dominant factor of determining money supply—called H theory of money supply’—also called money-multiplier theory of money supply.

The actual measurement of money in the modern economy has become an extremely complex matter because a fairly large variety of financial assets exist in the economy that serves as money in one way or another. Before the growth of a large variety of ‘near monies’, the circulating media (ordinary money M) could be described adequately by the term ‘deposit money’ or ‘deposits’, since a good part of the ordinary money (M) that actually circulated in the economy consisted of demand deposits in ‘nations’ commercial banks. But it is too restricted now on account of the growth of new varieties of near monies.

Monetary base which is also called central bank money—consists of all reserves of financial institutions on deposit with the central banks and all currency in actual circulation or in the vaults of commercial banks. This central bank or base money which is also called ‘high powered money’ is the primary means through which the central bank can influence the total money supply in the economy.

It is also called high powered because every unit (rupee) of central bank money provides a support base for several units (rupees) of money in actual circle. The monetary base is important because changes in it have the power to produce multiple change circulating money. The size of the monetary base in turn changes or fluctuates with changes in asset and liabilities of the central bank.

Thus, what the central bank has under its control is the size of money base (central bank money)—Whether or not changes in the monetary base actually lead changes in money in circulation depends upon how the public (including banks and other finance institutions) react to such a change. It is for public to decide whether or not to change its holdings currency, deposits and financial assets that serve as money in response to change in monetary base. Hence, the link between monetary base and the total money in circulation is a real one ; though it is not an exact and mechanical one.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, let it be clear that:

(i) The total supply of money or stock is determined by the behaviour of banks in their decision concerning the size of reserve ratio they wish to maintain,

(ii) By the behaviour of the non-bank public in their decision to divide their money balances between currency and demand deposits at commercial banks; and

(iii) By monetary authorities in their decision to change the size of the monetary base and the exercise of their legal authority to set the minimum amount of reserves banks must hold.

It is, therefore, clear that interactions among the actions of the public, the banks and the monetary authorities (central banks) determine the money supply. Behaviour of the public depending on currency deposit ratio C/D, that of banks on reserve deposit ratio R/D and that of monetary authorities by the stock of high powered money or the monetary base H. However, keeping in line with the recent developments in monetary theory, it will be fruitful to adopt the narrow concept of money—currency plus demand deposits—based on the means of payment criterion which facilitates the formulations of a theory of asset choices.

Further, it may also be noted what we exclude from the money supply of a country—the monetary gold stock which serves as international money and is not permitted to circulate within the country; as also we must exclude the currency and demand deposits owned by the treasury, the central bank, and the commercial banks, which are money issuing institutions holding these funds partly as reserves to support publically owned demand deposits.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These exclusions are in order because their inclusion i.e., of both the cash holdings of money issuers and the monetary super-structure supported by these holdings would involve double counting. Thus, for all practical purposes, the money supply with public consists of currency (notes and coins) and demand deposits with banks.

In the income and employment analysis quite often money supply is taken and as exogenous variable (depending on the administrative action of the central bank). This convenient simplification has been followed in the employment theory from time to time. But in actual practice the empirical studies on money supply data have shown that it is not at all necessary to assume that the money supply is exogenous—that is, unrelated functionally to other variables in the economic system.

The trend in recent analysis (especially after Friedman) is to treat money supply endogenously, as a variable functionally related to other variables in the economic system. A useful approach along those lines has been developed by Ronald Teigen (of University of Michigan). He suggests a money supply function that reflects both—the profit maximising decisions of the commercial banks and the policy actions of the Central Bank.

It is, therefore, clear that changes in H are policy controlled—while changes in M are largely endogenous, that is, are such as depend mainly on the behavioural choices of the public and banks. That is why it is said that monetary authority will do well to consider M as something outside its control and concentrate its efforts to control H in order to control M. Efforts to control M directly except through H route (or base money) are bound to prove self-defeating.

Supply of Money—Its Main Components:

It is by now clear that the main components of the supply of money are coins (standard money): paper currency and demand deposits or credit money created by commercial banks:

The term ‘Monetary Standard’ refers to the type of standard money used in a monetary system. As a matter of fact, the monetary system of a country is generally described in terms of its standard money. The monetary standard, therefore, is synonymous with the standard money. (Monetary systemconsists of its standard money plus all the paper and credit substitutes tied to and convertible into standard money). When the standard monetary unit is gold, a country is said to have a gold standard system; if the standard monetary unit is defined in terms of both gold and silver, the system is one of bimetallism.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If, however, a country’s currency is not convertible in either gold or silver, it is said to be an inconvertible paper money standard. Thus, it is customary to describe the monetary system of a country in terms of its standard money which constitutes the chief source of its supply. It may be noted that the adoption of a particular monetary standard in a country at a particular time, depends upon the economic conditions prevailing there. However, monetary standard which, thus, becomes an essential part of the monetary system, has to be such as will facilitate elastic money supply, economic development and promote the welfare of the people.

A suitable monetary system is one which satisfies both domestic requirements and the necessities of international trade. Generally speaking, the monetary system and, therefore, the monetary standards are guided by internal needs of a particular country, though the international aspects of currency management cannot be ignored.

Countries are no more closed economies. A good money supply system is based on good monetary standard; it must be certain inasmuch as its rules should be clear to the public; simple in working and should be able to create confidence in the public mind besides being economical. Moreover, a good monetary standard or money supply system, should ensure automatic working and control over excessive issue of money supply.

Further, it has to be elastic so that currency can expand and contract according to the requirements of the economy and, above all, it should be able to secure stability of prices as well as rates of exchange. It is, however, difficult to find a unique monetary standard or money supply system which entirely satisfies both domestic and international requirements of money supply. It has, therefore, assumed different forms from time to time. The standard money or a system of money supply, when it consisted of gold coins took the form of either gold coin standard or gold bullion standard or gold exchange standard.

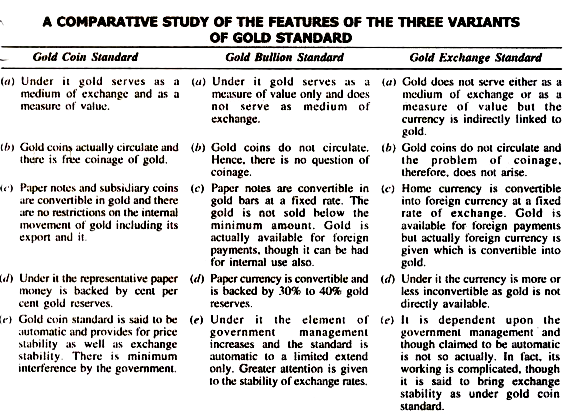

A comparative study of their features is given in the table below:

Thus, a comparative study of the features of the three variants of the gold standard would convince anyone about the efficacy of the post war gold standard variants (gold-exchange standard and gold-bullion standard) and the system of money supply based on it. Gold-exchange standard is said to have, more or less, the same uses as the gold-coin standard, at the same time economizing the use of gold and freeing the authorities from the botheration of coinage.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This made it possible for the poor countries to reap the benefits of gold-coin standard and was more in accordance with the monetary environment prevailing in the post-World War, though such a system of money supply called for greater monetary management. It is rather difficult for any one variant of the gold standard to claim undisputed supremacy regarding the regulation of money supply and its control. Having dismissed bimetallism as the standard which does not merit serious consideration, gold-coin standard was strongly favoured.

Though a causality of the two World Wars and the Great Depression, it still commands respect and even liking in certain circles, leaving the choice in favour of a particular variant under the circumstances prevailing in a country. However, modern system of money supply is primarily based on managed currency system.

Paper Currency:

The paper currency also described as the managed currency standard or the fiat standard, refers to a monetary system in which the standard currency of the country in circulation consists mainly of paper money. Paper standard or the fiat standard as distinguished from metallic standards is essentially the by-product of the World War I, for, before that, world currencies consisted mainly of full-bodied coins made of silver or gold or both.

The period following the World War I ushered in an era of inconvertible paper money. The paper standard or the fiat standard or the managed standard is distinct from other monetary standards inasmuch as, under it, there is no convertibility of the paper currency in any metal. As a result, the volume of paper currency is determined by the considerations of convenience and economic activities rather than by the volume of metal. Moreover, paper currency system is nationalistic as there is no common link between the different currency systems.

Thus, the important features of paper currency standard are:

1. Paper money is the standard money and is accepted as unlimited legal tender in the discharge of obligations;

2. Paper money is not convertible into gold or any other metal;

3. The volume of paper currency is controlled by the monetary authority (central bank), which expands or contracts the currency according to the requirements of the economy;

4. Though the standard money is made of paper, there may be in circulation metallic coins also being unlimited legal tender;

5. For purposes of foreign trade the rate of exchange is determined on the basis or parity between the purchasing power of the currencies of the respective countries.

Suppose one dollar in the United States has the same purchasing power is hundred francs in France, then one dollar will be equal to 100 francs. Since the intrinsic value (real value) of paper money is less than its value as money (face value) and further as it is not convertible into some other form of metal money, it is also referred to as fiat money and the standard as fiat standard. Moreover, the quantity of money in circulation is regulated and managed by the appropriate monetary authority in the country with a view to bringing stability in prices and incomes; therefore, it is also called managed currency system.

The backbone of the currency system is the central bank notes and coins because central bank has the monopoly of note issue, though in certain countries the treasury also issues notes or coins along with the central bank. In India, for instance, one rupee notes are issued and managed in circulation by the government of India, Ministry of Finance, and the rest of the notes and coins are issued and managed by the Reserve Bank of India. Supply of paper money in the country is governed by the system laid down for the purpose.

Broadly speaking, there are three important methods of note issue:

(i) The fixed fiduciary system,

(ii) The proportional reserve system, and

(iii) Minimum reserve system.

The first one is in vogue in UK and the second one is prevalent in USA and the third one in India at present. In India proportional reserve system also prevailed up to mid-1950s. Then the minimum reserve system replaced it. How much currency of particular denomination will be in circulation and its proportion to the total money supply are governed by the actions of the public.

The treasury, the commercial banks and the central bank are the agencies through which the preference of the public is expressed. According to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Neither the central bank nor the treasury has under ordinary circumstances any direct way of keeping in circulation a larger amount of currency than the public requires or of reducing the amount of currency that the public needs to finance its current operations”.

The desire of the public to hold more or less currency or more or less of particular denominations is normally influenced by many factors like the volume of trade, nature of trade—whether wholesale or retail price level, methods of payments, banking habits of public, volume of demand deposits, volume of transactions, distribution of national income, methods of taxation, public loans, deficit financing, etc.

Demand Deposits:

In most of the economically advanced countries like UK and USA the bulk of the total supply of money is deposit money which refers to the commercial banks’ total demand deposit. As such the course of behaviour of the internal price level is greatly affected by changes in the volume of deposit money or bank credit. These demand deposits of the commercial banks are the outcome of the public deposits with the banks, and bank loans, advances and investments.

The public deposits which are cash deposits are called ‘primary deposits’ because they are the result of the real savings of the people and deposits which are the result of banks’ loans and advances to customers are called ‘derivative deposits’ and represent the creation of credit by banks. The relative amounts of the two main sources of money supply, viz., the currency and demand deposits, depend upon the degree of monetization of the economy, banking habit, banking development, trade practices, etc. in the economy.

For example, almost 80 per cent of the money supply of the US is made of demand deposits. While in underdeveloped countries like India, the proportion of the currency money to the total money supply with the public is considerably large because a very high percentage of transactions are performed through cash payments rather than credit instruments like cheques, etc.

Changes—Elasticity and Velocity of Money:

Although these terms are being used interchangeably in monetary economics, yet it would be useful to understand the distinction amongst these terms and to use them as such. Changes imply simple variations in the total quantum of money supply due to the changes in the expenditures of the government exceeding its revenue (through taxes and borrowings)—the supply of money in the economy may increase. This happens because the excess expenditure of the government sector is to be financed either by taking loans from the central bank or by selling government securities to the banking system or by way of printing more money (deficit financing), and this, in turn, changes the supply of money.

Similarly, the private sector (domestic and foreign) also affects the money supply by increasing or decreasing loans and advances from the banking system as also by making purchases and sales of shares and securities from and to the banking sector. These are all instances of a simple and ordinary change or variation in money supply.

The ability of the supply of the circulating media to adjust itself to changes in the volume of trade without affecting the general price level is often termed as ‘monetary elasticity’. In other words, ‘elasticity of money’ to adjust itself in an appropriate manner to implied changes in the needs for money is the ability in order to meet or mitigate the seasonal or cyclical monetary demand. Elastic money supply refers to the situation occurring in a monetary system in which the volume of currency in circulation can be varied to meet different needs.

The degree of monetary elasticity depends on the action and power of the central bank. If the money market is well organized and developed the central bank can perform the function of monetary elasticity with efficiency. Thus, a change in needs necessitates a change or variation in money supply and this, in turn, necessitates elasticity in the supply of money.

So far our analysis remained confined to the total supply of money at a moment of time. We are equally interested in finding out what the supply of money is over a period of time, say a year, and for this we have to bring into the picture what is called the velocity of circulation of money. It is the basic function of money that has to be re-spent.

The average number of times each unit of money changes hands or is spent on goods and services during a given period is called velocity of money. Therefore, the supply of money during a given period is the total amount of money in circulation (M) multiplied by the average number of times it changes hands during that period (V). In algebraic terms the supply of money during a given period is denoted by MV. Velocity will depend upon the time involved in receiving and spending the money, methods and habits of payments, trade and business conditions, liquidity preference, etc. A concept closely related to the transactions velocity of money is the income velocity of money, which is the number of times that money moves from one income recipient to another. It can be derived by dividing the total national product by the money supply.

The issue whether there is any ceiling to an increase in the income velocity of money is an unsettled one. Views on this matter differ sharply. The Radcliffe Report does not find “any reason for supposing or any experience in monetary history indicating, that there is any limit to the velocity of circulation.” In sharp contrast to this view, Newlyn contends that, “…a specialised exchange economy necessarily involves the holding of the medium of exchange over time. However, efficient the monetary system, there must, therefore, be some finite limit to the velocity of circulation and the more the rate of interest is prevented from rising by rationing, the lower this limit will be.”

Similarly, Ritter has argued that “as interest rates continue to rise, due to continued monetary restraint and persistent demand for funds, idle balances are likely to approach minimum levels. Correspondingly, velocity is likely to encounter an upper limit, a rough and perhaps flexible ceiling, but a ceiling nevertheless.” In brief, we can say that given the quantity of money there is likely to be a limit to the rise in money income or, in other words, there is ceiling to the rise in income velocity of money.