Neoclassical Theory of Money (Monetary Issues): With Graphs, Equations & Formulas!

Neoclassical theory of money has been developed as a part of reaction against the Keynesian revolution.

Keynes repudiated the classical theory of full – employment equilibrium and demonstrated the possibility of less – than – full employment equilibrium.

The counter – revolution which was initiated by Pigou in 1943, was successively mounted with greater strength by Don Patinkin and Milton Friedman, and recently by Brunner and Allen Meltzer.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These economists attempted to rehabilitate the classical theory. The monetary issues on which the neo – classical economists mainly concentrated are- neutrality of money, dichotomization of real and monetary sectors, and real balance effect.

1. Monetary Transmission Mechanism:

Monetary transmission mechanism or transmission mechanism of monetary policy is the process through which monetary policy decisions are transmitted into changes in gross national product (GDP) and inflation. This is the process through which monetary policy affects the economy in general and the price level in particular.

The monetary transmission mechanism describes how policy-induced changes in nominal money stock or the short-term nominal interest rate affect the real variables such as aggregate output and employment. In simple terms, monetary transmission mechanism refers to the process by which monetary policy decisions are passed on, through financial markets, to the businesses and households.

Specific channels of monetary transmission operate through the effects that monetary policy has on interest rates, equity and real estate prices, bank lending, and firm balance sheets. The transmission mechanism is characterised by long, variable and uncertain time lags. Thus, it is difficult to predict the precise effect of monetary policy actions on the economy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Three-Stage Process:

The transmission mechanism of monetary policy is a process by which interest changes affect GDP and inflation.

It is basically a three-stage process:

First Stage:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the first stage, a change in the official interest rate has four effects:

(i) It will affect market rates. Banks, building societies and other financial institutions have to react to any official rate change by changing their own savings and lending rates.

(ii) The change in official interest rate will also affect the prices of many assets, such as shares, houses, guild-edged security prices and so on.

(iii) The exchange rate may also change as demand and supply of foreign currencies adapt to the new level of interest rates.

(iv) Finally, there may also be an effect on the expectations of both firms and individuals. They may become more or perhaps less confident about the future path of the economy. Long-term future is more uncertain than short-term or immediate future.

Second Stage:

The second stage is that all these changes in the markets will affect the spending patterns of consumers and firms. In other words, there will be an effect on aggregate demand. Higher interest rates are likely to reduce the level of aggregate demand, as consumers are affected by the increase in interest rates and may look to cut back spending. There will also be international effects as the levels of imports and exports change in response to possible changes in exchange rate.

Third Stage:

The third stage is the impact of the aggregate demand change on output and inflation. This will tend to depend on the relative levels of aggregate demand and supply. If there is enough capacity in the economy, then an increase in aggregate demand may not be inflationary and may increase output and employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, if the economy is already at the bursting point producing as much as it can, then any further increase in aggregate demand may be inflationary,

Channels of Monetary Transmission:

Various channels through which monetary policy actions (as summarised by nominal money stock or short-term nominal interest rate) have their impact on aggregate output and employment are described below:

I. Keynesian Interest Rate Channel:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to the traditional Keynesian interest rate channel, a policy-induced increase in the short-term nominal interest rate produces the following sequence of effects:

(i) The increase in the short-term nominal interest rate leads first to an increase in longer-term nominal interest rates, as investors act to arbitrage away differences in risk-adjusted expected returns on debt instruments of various maturities.

(ii) When nominal prices are slow to adjust, these movements in nominal interest rates translate into movements in real interest rates.

(iii) Firms, finding that their real cost of borrowing has increased, cut back their investment expenditures.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iv) Likewise households, facing higher real cost of borrowing costs, reduce their purchases of houses, automobiles and other durable goods.

(v) As a result, output and employment fall.

II. Exchange Rate Channel:

In the open economies, additional real effects of a policy-induced increase in interest rates come about through the exchange rate change. When the domestic nominal interest rate rises above its foreign counterpart, equilibrium in the foreign exchange market requires that the domestic currency gradually depreciate at a rate that serves to equate the risk-adjusted returns on debt instruments dominated in each of the two countries.

This expected future depreciation makes domestically produced goods more expensive than foreign-produced goods. As a result, net exports fall, domestic output and employment fall as well.

III. Asset Price Channel:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Additional asset price channels are highlighted by Tobin’s theory of investment and Ando and Modigliani’s life-cycle theory of consumption.

(i) According to Tobin, a policy-induced increase in nominal interest rate makes debt instruments more attractive than equities in the eyes of investors. Hence, following a monetary tightening, equilibrium across securities markets must be re-established through a fall in equity prices. As a result, each firm must issue more new shares in order to finance any new investment projects. In this sense, investment becomes more costly. In such conditions, the investment projects that were only marginally profitable before the monetary tightening go unfunded, leading output and employment to decline.

(ii) Ando and Modigliani’s life-cycle theory assigns a role to wealth as well as income as key determinants of consumer spending. Hence, this theory also identifies a channel of monetary transmission. If stock prices fall after a monetary tightening, household financial wealth declines, leading to a fall in consumption, output and employment.

IV. Credit Channel:

An open market operation that leads first in a contraction in the supply of bank reserves and then to a contraction in bank deposits requires banks to cut back their lending and the firms that are dependent on bank loans to cut back on their investment spending. Individual banks and firms thereby contribute to the decline in output and employment that follows a monetary tightening.

V. Balance Sheet Channel:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A direct effect of monetary policy on the firm’s balance sheet comes about when an increase in interest rates works to increase the payments that the firm must make to service its floating debt. An indirect effect also arises when the same increase in interest rates works to reduce the capitalised value of the firm’s long-lived assets.

Hence, a policy-induced increase in the nominal rate of interest not only acts immediately to depress spending through the traditional interest rate channel, it also acts, possibly with a lag, to raise each firm’s cost of capital through the balance sheet channel deepening and extending the initial decline in output and employment.

VI. Monetarist Channel:

The monetarists criticised the traditional Keynesian model by questioning the view that the full thrust of monetary policy actions is completely summarised by the movements in the short- term nominal interest rate.

Monetarists argue instead that monetary policy actions affect prices simultaneously across a wide variety of markets for financial assets and durable goods, but especially in the markets for equities and real estate. These asset price movements are all capable of generating important wealth effects that have their impact, through spending, on output and employment.

VII. New-Keynesian Channel:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Recent theoretical work on the monetary transmission mechanism seeks to understand how the traditional Keynesian interest rate channel operates within the context of dynamic general equilibrium models.

The basic New Keynesian model is built on the combination of the key assumption of nominal price or wage rigidity with the assumption that all agents have rational expectations. According to the rational expectations hypothesis, the policy makers are unable to generate systematic forecasting error in the private sector, and cannot, therefore, systematically alter output and employment.

The New Keynesian model which involves three variables: output, inflation and short-term nominal interest rate, explains the monetary transmission mechanism in terms of the IS curve, the Phillips curve and future expectations. The IS curve slopes downwards indicating that as interest rate rises, income and expenditure falls.

Each point on the IS curve is a point of equality between saving and investment, indicating equilibrium in the product market. The Phillips curve is a downward sloping curve representing inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation (or positive relationship between output and inflation).

The conclusions of the model are:

(i) A monetary tightening that increases the snort-term nominal interest rate translates into an increase in the real interest rate as well when nominal prices move sluggishly due to costly or staggered price setting.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) This rise in the real interest rate then causes households to cut back on their spending (as described by the IS curve) which leads to the decline in output.

(iii) Finally through the Phillips curve, the decline in output puts downward pressure on inflation.

(iv) Importantly, however, the expectational terms which enter into the model imply that policy actions will differ in their quantitative effects depending on whether these actions are anticipated or unanticipated.

Three Basic Approaches:

There are many different views of monetary transmission mechanism. These views differ in the emphasis they place on money, credit, interest rates, exchange rates and prices or the role of commercial banks and other financial institutions. Broadly, there are three basic approaches or models of monetary transmission mechanism.

They are:

(a) Classical Approach:

The classical economists believe in the neutrality of money which means that changes in the money stock do not produce any change in the real variables. The only lasting effect of money is on the general price level.

(b) Keynesian Approach:

The Keynesians believe that in the short run, under the conditions of unemployment, changes in money supply will produce permanent non-neutral effects, i.e., will permanently change the rate of interest and the employment level.

(c) Monetarist Approach:

The monetarists believe that money is non-neutral in the short run and the short run may be considerably long. However, such non-neutrality is essentially transitory depending upon the time it takes labour and lenders to perceive inflation and adjust to it.

2. Neutrality of Money:

Money is said to be neutral if changes in the stock of money change only absolute prices and leave relative prices unaltered. On the contrary, money is non-neutral when changes in the stock of money influence relative prices. In other words, when money supply changes affect only monetary phenomenon and do not at all affect real phenomena, money is neutral.

Neutrality of money means that changes in money stock has no influence on the level of real income, the real rate of interest, the rate of capital formation, and the volume of employment. The only influence of a change in the money stock is to alter the general level of prices.

The policy of maintaining neutrality of money is called the policy of neutrality of money. This policy seeks to do away with the disturbing effects of changes in the quantity of money on important economic variables like income, output, employment and prices. According to this policy, money supply should be controlled in such a way that money should be neutral in its effects.

The notion of neutrality of money has been viewed differently by different economists. Broadly, there are three different views as presented by the classical economists, the Keynesians and the monetarists.

The views are:

I. Classical View:

The classical economic analysis is based on the fundamental belief that ‘money is neutral’ or ‘money is veil’ or ‘money does not matter’. For the classical economists, the neutrality of money meant that changes in the money stock or its rate of growth could not produce changes in the equilibrium value of real variables. The only lasting influence of money was on the general level of prices. The classical economists, however, admit short- run-non-neutrality of money.

According to the classical economists, money serves only as a medium of exchange; people hold as little money as possible, for as short a period as possible, in order to make transactions. Changes in money supply are neutral in the sense that they affect the absolute prices and not the relative prices.

Increases in money supply cause all prices to rise at the same rate and decreases in money supply cause all prices to fall at the same rate. Because consumer spending and business spending decisions depend upon relative prices, changes in the money supply do not affect real variables, such as employment and output Thus, money is neutral.

In order to understand how changes in money supply affect only monetary, and not real, phenomena, let us analyses the effects of an increase in money supply. Money being only a medium of exchange, an increase in money supply increases money or nominal income, which, in turn, leads to an increase in the general demand for, and, thereby, the absolute prices of goods and services.

Given the money wages, the rise in price level lowers the real wage. Given the demand for and supply of labour curves, a reduction in the real wage causes a shortage of labour. Free labour markets will therefore experience increase in money wages until equilibrium is again restored. Thus, changes in money supply leads to proportional increases in the prices and money wages, but real wages and employment remain unchanged.

If changes in relative (real) prices temporarily result from the changes in money supply, then shortages (where prices have fallen) and surpluses (where the prices have risen) will arise. Competition in the markets will, through demand and supply forces, raise the prices where they fell and lower the prices where they rose, and thus eventually restore equilibrium at the original relative prices.

To the classical quantity theorists, money is neutral or money does not matter because money serves only as a medium of exchange. This can be explained through Fisher’s Equation of Exchange (MV = PY) as well as Marshall’s Cambridge Equation (M = KPY) which are essentially identical because of the inverse relationship between V and K (i.e., V = 1/K or K = 1/V).

(i) Given the demand for money, change in the money stock changes the price level, leaving relative prices unaltered. Assuming velocity of money (V or 1/K) and real income (Y) constant, as the stock of money (M) increases, the price level (P) also increases proportionately.

(ii) Given the supply of money, changes in demand for money also change the price level. An increase in the frequency of payment to income recipients will increase V (or will lower K). Thus, given the stock of money (M) and the real income (Y), an increase in V leads to a proportionate increase in the price level (P), leaving relative prices unchanged.

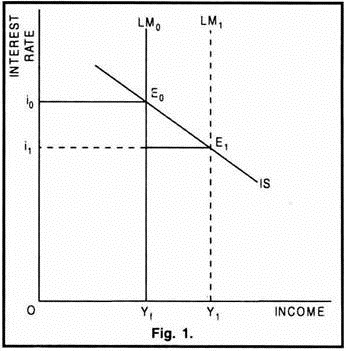

The classical view of neutrality of money is graphically shown through IS-LM curves in Figure -1. In the classical system, the LM curve is a vertical line at full employment level Yf. The classical economists assumed that the supply of money or the lending policy of the banks is not influenced by the market or money rate of interest.

The vertical LM curve at full employment shows that, given the money supply, a maximum level of real national income (Yf) can be possibly obtained; assuming that money is held only for exchange purposes and therefore velocity of money is maximum.

Initial equilibrium is at E0 where the IS curve intersects the LM0 curve at full employment real income level Yf and the rate of interest is i0. When the supply of money increases, the LM curve shifts to the right from LM0 to LM1, As a consequence, the new equilibrium level E1 is obtained where the market interest rate has fallen from the equilibrium rate i0 to i1 and the nominal income has increased from the equilibrium level Yf to Y1.

The excess demand (YfY1), resulting from the increases in the nominal income, will force the price level to rise. This will reduce the real money stock (i.e., dividing nominal money stock by prices or M/P). As a result, the LM curve will shift back from LM1 to LM0. Once again, full employment equilibrium is restored at Yf.

Thus, at any income level other than full employment income Yf, changes in the level of prices will shift the LM curve in the direction of full employment income. Money is neutral in its impact on the economy. In other words, a change in the nominal money stock (M) can have no long-run effect on real output, the level of employment or the composition of final output

II. Keynesian View:

The Keynesians believe that in the short run, under the conditions of unemployment, changes in money supply will produce permanent non-neutral effects, i.e., will permanently change the rate of interest, the level of employment, the rate of capital formation, etc. All this means that money is non-neutral in the short period.

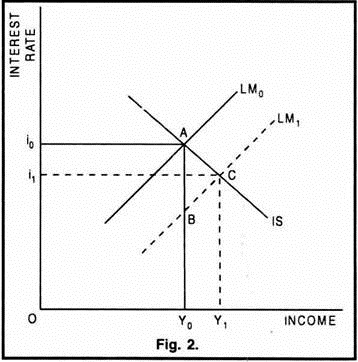

Figure-2 illustrates the Keynesian position of non- neutrality of money. In the Keynesian analysis, the LM curve is a positively sloping curve (LM0) indicating that as the national income falls, the demand for money for transactions and precautionary motives will fall and more cash balances are held for speculative motive. Point A represents the initial equilibrium of the economy at less- than-full employment level; Y0 is the real income level and i0 is the rate of interest.

An increase in the money supply will shift the LM curve from LM0 to LM1. As a result, the economy will move from point A to C, the real income will increase from Y0 to Y1, and the rate of interest will fall from Y0 to Y1. The degree of change in the real income and the rate of interest depends upon the slope of the IS curve.

The movement from A to C, as a result of expansion in money supply, involves two effects:

(a) The liquidity effect (i.e., the movement from A to B); and

(b) The income effect (i.e., the movement from B to C).

If during the process of increase in output, there is any rise in the price level, the LM1 curve will shift to the left and the ultimate equilibrium level will move to a point left to C, thus reducing the real income (from Y1) and increasing the interest rate (from i1).

The degree of non-neutrality of money in the Keynesian analysis depends upon a number of factors:

(a) The income and interest elasticity’s of money demand;

(b) The interest elasticity of expenditures;

(c) The income elasticity of the saving schedule (which governs the multiplier);

(d) The degree to which the marginal productivity of labour diminishes; and

(e) The extent to which the productive factors suffer from money illusion.

The belief that money has permanent non-neutral effect has an important policy implication for the Keynesians.

They treat changes in nominal variables as leading to equivalent changes in their real counterparts. For example, nominal interest rate has often been used by the Keynesians as a measure of monetary tightness or ease.

However, there exist two situations in the Keynesian analysis which render money neutral:

(a) In a situation of liquidity trap (i.e., deep depression), all changes in the money supply are added to the idle balances and have no effect on any real variable; thus money is neutral.

(b) In the Keynesian model, money affects the real sector only through interest rate. If expenditures are insensitive to changes in the interest rate (e.g., in a situation of full employment), then money is neutral because money affects the interest rate and nothing else.

III. Monetarist View:

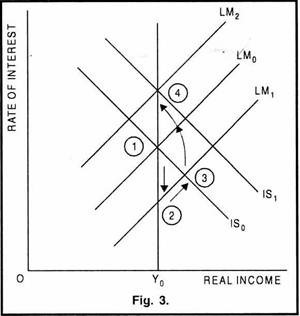

The monetarists believe that money is non-neutral in the short run and the short run may be considerably long. However, such non-neutrality is essentially transitory depending upon the time it takes labour and lenders to perceive inflation and adjust to it. The monetarist view of the transitory non-neutrality of money in the short period is illustrated in Figure 3.

In Figure 3, the initial equilibrium level of income, unemployment, and rate of interest is shown by point (1). An increase in the rate of growth of money will drive down the rate of interest from (1) to (2) as a result of the rightward shift in the LM schedule (from LM0 to LM1).

However, two forces are set in motion which tends to push the rate of interest back in the direction of its initial equilibrium point (1):

(i) Income Effect:

This represents the rise in the interest rates due to the expansion of aggregate demand set in motion due to the decline in the rate of interest. Thus, the rate of interest will rise to point (3), the real income will expand beyond Y0 and unemployment will fall below its natural rate.

(ii) Price Expectation Effect:

In order to reduce unemployment and expand real income, the price level must rise.

As a result of the rise in prices, two changes will occur:

(a) The LM schedule will shift to the left (from LM1 to LM2) as real money balances decline;

(b) To the extent that lenders perceive the inflation, the IS schedule will shift upward (from IS0 to IS1) by the amount of that perception as they demand a higher money interest rate to compensate them for the loss in purchasing power.

This price expectation effect will move the market interest rate towards a position such as point (4), above point (1) by the amount of expected inflation. If no expectations of inflation develop, the economy will move back to point (1), once the real wage relationship is restored. The movement from point (1) to (2), to (3), and to (4) traces out the period of transition, or short period.

Conditions of Neutrality:

For the strict neutrality of money to prevail, the following four conditions must be satisfied:

i. Flexible Prices:

Neutrality of money requires that a change in the quantity of money leads to an equi-proportionate change in all prices. In other words, (a) the increase in money supply is distributed among all money holders in such a way that everyone’s money balances increase by a given proportion A, and (b) all prices are revised upward to (1 + λ) times their base value.

If this occurs without a time lag, then the neutrality of money is instantaneous. But if time lags are involved in the adjustment process, then there tends to be a long-term neutrality of money. The long-term neutrality is ensured through flexible factor and commodity prices.

ii. Absence of Money Illusion:

Neutrality of money requires absence of money illusion from all demand and supply functions. This implies that individual economic units base their decisions not on money magnitudes but only on real values or relative prices.

The economy is split up into two completely independent sectors in which all real magnitudes and relative values are determined in the real sector and all nominal magnitudes and absolute prices are determined in the monetary sector. Thus all demand and supply functions of the real sector are insensitive to changes in the absolute money prices; money is neutral in its impact on real variables.

iii. Absence of Distribution Effect:

Neutrality of money requires the absence of distribution effect, which implies that as a result of change in money, the relative money balances of individuals do not change. Thus, a change in the quantity of money will lead to an equi-proportionate change in everyone’s money balances which will put an equi-proportionate pressure on demand for all goods, thus leaving their relative prices unaffected.

In practice, the condition of absence of distribution effect is difficult to be satisfied:

(a) It is practically impossible to have an equi-proportionate change in everyone’s money balances.

(b) Even if this happens, the equi-proportionate effect on demand for all goods is not possible because of varying income elasticity’s of demand of different individuals for different goods at different income levels,

(c) Relative prices are affected not only by demand elasticity’s, but also by supply elasticity’s. Shifts in demand will cause changes in output of some goods, thus disturbing the relative, prices.

iv. Absence of Price Expectations:

Another condition for neutrality of money is the absence of price expectations.

The expectations regarding price changes can cause shifts in the demand pattern for assets and thus disrupt the relative prices in two ways:

(a) The wealth owners try to switch over from assets whose prices are expected to increase less to those whose prices are expected to increase more,

(b) Even if all prices are expected to rise equi-proportionately, there will be a shift from money to real assets.

Inside and Outside Money and Neutrality Condition:

Distinction between inside and outside money is very important in understanding the effect of changes in money on the neutrality of money. The distinction is based on the assumption that the economy is to be regarded as the private sector and the government as foreign to the economy.

Thus inside money refers to the financial claims of economic units in the private economy on other economic units within the economy. Outside money is the government money which is a liability of the government as a debtor and a claim of the private sector as a creditor.

Gurley and Shaw have shown that neutrality of money can be ensured with only inside money or only outside money, but not when both types of money are in existence. With only inside money, any increase in the net wealth of the creditors will be counter-balanced by a corresponding reduction in the net wealth of the debtors and there will be no change in the net wealth of the community. Money remains neutral.

With only outside money, an increase in it causes a corresponding increase in the net wealth of the economy, which also leads to a corresponding rise in the price level, leaving the relative prices unchanged. Again money is neutral. But the existence of both inside and outside money disturbed the neutrality of money, because a change in prices in response to one kind of money only restores its value to the original level, but not that of the other part of money.

Even the existence of only inside money or only outside money lead to non-neutrality of money through their effect on distribution of wealth. Though the change in inside money does not change the net wealth of the community as a whole, but it certainly affects the distribution of wealth.

If, therefore the demand pattern of the creditors is different from that of the debtors, the effect is bound to be non-neutral one. The distributional effect of the outside money becomes clear when we note that outside money must enter the economy somewhere and then work its way through changes in the demand and supply patterns.

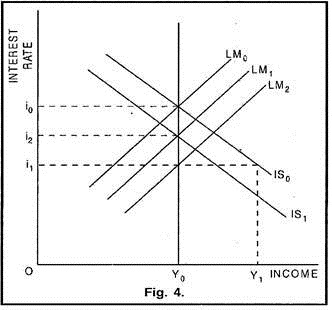

Lloyd Metzler has criticised the theory of neutral money with the help of general equilibrium analysis through IS-LM curves as illustrated in Figure-4. The initial equilibrium income and rate of interest corresponding to a full employment situation are simultaneously determined by the intersection of LM0 and IS0 curves at Y0 and i0 respectively.

If the central bank follows a policy of open market operations and starts purchasing bonds, the nominal stock of money will increase, causing a shift in the LM curve from LM0 to LM2. This will determine equilibrium at a lower interest rate i1 and the income level Y1. There is now an excess of income over the full employment income equal to Y0Y1 which represents the inflationary gap.

This will initiate an inflationary process. The real balance effect will become operative and the LM curve will shift to LM1. The IS curve will also shift from IS0 to IS1 on account of reduction in consumption spending as a result of a fall in real balances. This will restore the equilibrium again at full employment income Y0. But, since the rate of interest has fallen from i0 to i2, money cannot be considered neutral.

3. Dichotomisation of Pricing Process:

The classical economists, on the assumptions of neutrality of money (i.e., money serves only as a medium of exchange and changes in money supply affect the absolute prices and not the relative prices) and the absence of money illusion (i.e., the buyers and sellers react to changes in relative, and not absolute, prices), dichotomised the pricing process into its real and monetary aspects and thus separated the money market from the real (or commodity) market.

The quantity theory of money justifies this dichotomy. According to the classical economists, the relative (or real) prices are determined in the commodity market and the absolute (or nominal) prices are in the money market.

Since money is neutral and changes in money supply affect only the monetary, and not the real phenomena, the classical economists developed the theory of employment and output entirely in real terms and separated it from their monetary theory of absolute prices.

The real wage and the levels of employment and output are determined by the real factors, i.e., the marginal productivity of labour and the marginal disutility of labour (or the demand and supply of labour).

On the other hand, money wages and absolute prices are determined solely by monetary factors. Changes on the real side can affect relative prices and wages, but changes on the monetary side have no effect on the real variables. Thus, the real theory of value is separated from the monetary theory of value, and the real sector from the monetary sector.

Thus, if there is only accounting money in the system, the demand functions for commodities depend only on relative prices and not on the absolute price level. Mathematically speaking, the demand functions for commodities are ‘homogeneous of degree zero’ in absolute money prices because they are not affected by an equi-proportionate change in the determining prices.

This insensitivity of the demand functions of the real sector to changes in the absolute money prices is referred to as the ‘homogeneity postulate’ and is said to denote the absence of money illusion.

Such demand functions are, however, deficient because they do not recognise the presence of money balances. Cash-balance approach of the quantity theory of money deals with money balances. Money balances may be introduced in the analysis of the dichotomisation of the pricing process in two ways; (a) by considering the demand for money balances, and (b) by considering the supply of money balances.

On the demand side, the classical dichotomy is based on the constancy of the proportion of real resources which people like to hold in the form of cash balances. It is assumed that the people are interested not in any given amount of money balances but only in their real purchasing power. Thus, demand for money is constant if measured in terms of its purchasing power.

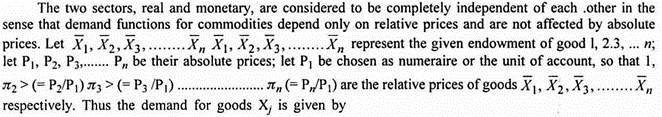

Figure 5 shows the nature of demand curve for real balances and demand curve for nominal balances. In the absence of money illusion, the demand for real money balances depends only on relative prices and real wealth. If money holdings (M) are converted into real balances (M/P), then their demand is always for a constant amount (M0/P0).

Since demand is insensitive to price changes, the demand curve for real balances is parallel to the price axis (Figure 5 – A). The demand curve for nominal balance will for the same reason, be a rectangular hyperbola which shows that the increase in nominal money balances is exactly proportional to the reduction in price level and vice versa (Figure 5-B).

On the supply side, dichotomisation of the real and monetary sectors implies that changes in the quantity of money do not lead to real-balance effect, i.e., the changes in the purchasing power of money balances leave demand functions for commodities unaffected.

Conditions for Dichotomisaton:

The neoclassical dichotomisation means that the real variables (e.g. output, employment, real wage, interest rates, etc.) are determined entirely in the real sector, and the monetary variables (e.g., the absolute price level, the nominal wage, etc.) are determined entirely in the financial sector.

This further implies that real sector (i.e., the labour and commodity markets) can be separated from the financial sector (i.e., the bond and money markets) and the real markets are capable of determining the equilibrium values of all the real variables. In other words, the real sector model is said to be separable or dichotomisable if it consists of a self- contained subset of equations from which the solution of all the real variables can be obtained.

The possibility of dichotomisation of real economic analysis from monetary economic analysis depends solely whether or not some form of real balance variable appears among the equations of the real sector.

This variable can be either- (a) real outside money, or (b) real government debt, or (c) a mixture of the two. Thus, as long as the real balance variable appears in any of these three forms, dichotomisation is not valid. On the other hand, when there is no real balance variable in the real markets, dichotomisation is valid.

Consider an economic system which is based on the strict version of quantity theory of money and in which money is neutral. Further assume that all money is inside money (primarily modern money system) and that no government debt exists (basically a classical fiscal system).

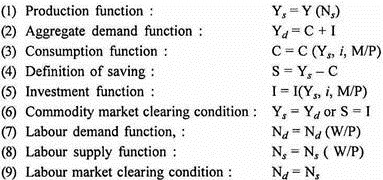

Such an equational system is given below:

Real Sector:

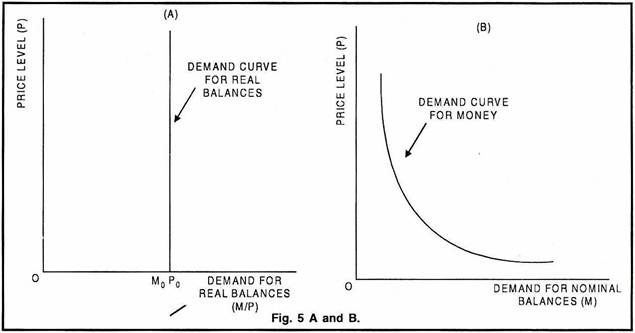

The real sector includes commodity market (Equations (1) to (6) and labour market (Equations (7) to (9)).

(1) Production function- YS = YS (Ns)

(2) Aggregate demand function- Yd = C + I

(3) Consumption function- C = C (Ys, i)

(4) Definition of saving- S = (Ys – C)

(5) Investment function- I = (Ys, i)

(6) Commodity market clearing condition- Ys = Yd or S = I

(7) Labour demand function- Nd = Nd (W/P)

(8) Labour supply function- Ns = N (W/P)

(9) Labour market clearing condition- Nd = Ns

Monetary Sector:

Equations (10) to (12) represent monetary sector.

(10) Money demand (or liquidity preference) function-

Md = P.L (Y, i)

or Md/P = L (Y, i)

or Md/P = L1 (Y) + L2 (i)

(11) Money supply function- Ms = M̅s

(12) Money market clearing condition- Md = Ms.

where Ys = Real income or output

Yd = Aggregate demand

C = Real consumption

S = Real Saving

I = Real investment

i = Rate of interest

Nd = Demand for labour

Ns = Supply of labour

W/P = Real wage (money wage divided by the price level)

Md = Demand for cash balance (or nominal money)

P = Absolute price level

Ms = Money supply which is exogenously fixed at M̅s level

L1 = Amount of money demanded for transactions and precautionary motives.

L2 = Amount of money demanded for speculative motive.

For an equational system to be determinate, the number of equations must be equal to the number of unknowns. In the real sector, there are nine equations and nine unknowns (Ys, Yd C, S, I, i, Nd, Ns, W/P). Thus, the real sector consists of a self-contained subset of equations and the equilibrium values of all the real variables can be determined from these real sector equations alone. Hence, the real sector is separable from monetary sector; the system dichotomies.

In the money market, supply of money is exo-geneously fixed at M̅s . The equilibrium values of Ys* and i* have already been known. Thus, we are left with two equations (10) and (12) and also two unknowns (Md and P). With known Ys and i, Equation (10) is equivalent to –

Md/P = constant

which is the equation of rectangular hyperbola and is expressed by the rectangular hyperbolic curve in Figure-6D. It can be seen clearly in Figure-6 D that as the exogenously determined supply of money doubles from M̅s to M̅s the absolute price level also doubles from P* to 2P*.

That is, the strict quantity theory holds. Thus we conclude that in a situation under consideration (i.e., when all money is inside money and there is no government debt) strict quantity theory holds, money is neutral (i.e., it has no effect on interest rate) and the model is dichotomisable.

Money is neutral if a change in the supply of money changes the nominal variables alone and leaves the real variables unaffected. When money is neutral, strict version of the quantity theory of money holds, i.e., the change in prices is proportional to the change in the supply of money.

The necessary conditions for the neutrality of money are:

(a) All the prices are flexible;

(b) Expectations are unit elastic;

(c) Money illusion is absent from every demand and supply function; and

(d) There is no distribution effect.

On the other hand, dichotomisation is valid when no real balance variable either in the form of real outside money, or real government debt, or a mixture of the two appears in the real sector model. In order to analyse the possibility of both neutrality of money and dichotomisation of real and monetary sectors, three cases may be considered.

Throughout the analysis, we assume the prevalence of the neutrality conditions:

Case I- All Money is outside and There is no Government Debt:

This is primarily a classical case because in the classical times, money was mainly fiat or commodity money and the governments were not fiscally active, except in times of war. In this case, money is neutral because all the four neutrality conditions are fulfilled. Strict version of the quantity theory of money operates. However, dichotomisation is not valid because, real balance variable in the form of outside money appears in the real sector model.

Case II- All Money is inside and There is Government Debt:

This case represents the modern situation because nowadays most money is bank money and there exists large government debt. In this case, when the government sector has been introduced, money illusion is bound to affect the system. Thus, money is no longer neutral. Strict version of quantity theory of money does not hold, i.e., prices respond to changes in the supply of money, but not proportionately.

Dichotomisation in this case is not valid because the real balance variable in the form of real government debt (undiscounted for implicit future taxes) appears in the real sector. In other words, the equilibrium values of the variables of the real sector cannot be independently determined without the help of monetary sector.

Case III- All Money is inside and There is no Government Debt:

This is a hybridised and not very realistic case. On the one hand, it assumes a basically modern monetary system in which all money is inside money. But, on the other hand, it also assumes a basically classical fiscal position when no government debt exists.

In this case, money is neutral because of the fulfillment of all the four conditions of neutrality. The strict version of the quantity theory of money prevails. Moreover, the system dichotomises because no real balance variable appears in the real sector.

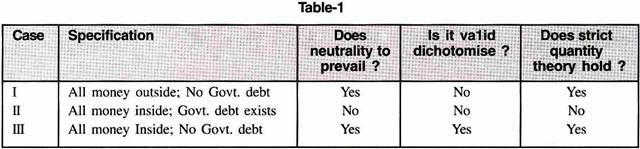

The conclusions of the above three cases are summarised in Table -1:

Integration of Monetary and Real Sectors:

The classical dichotomy between the monetary and the real sectors has been rejected by the later economists like Keynes and Don Patinkin who also attempted to integrate the two sectors:

I. Keynes’ Integration of Monetary and Real Sectors:

In his General Theory, Keynes successfully integrated the theory of money and the theory of value and thus the monetary sector and the real sector. This integration is achieved through rate of interest.

Keynes believes that the relationship between the quantity of money and prices is indirect and uncertain, and not direct and proportionate as considered by the classical thinkers. He visualised the impact of a change in the supply of money on prices via its impact on rate of interest, level of investment, output, employment, which, in turn, will lead to an increase in output, and income.

The prices rise because of a number of factors like the rise in labour costs, bottlenecks in production process, operation of the law of diminishing returns, etc. Thus, Keynes integrates the theory of money and the theory of prices and the rate of interest is the link between the monetary sector and the real sector.

II. Patinkin’s Integration of Monetary and Real Sectors:

Don Patinkin also integrated the monetary and the real sectors but through a different mechanism. He regarded the dichotomy between the two sectors as invalid and unnecessary. By considering real balances as an important determinant in the demand functions for commodities, Patinkin not only overcame the dichotomy, but also rehabilitated the quantity theory of money.

He integrated the monetary sector and the real sector by emphasising that relative price cannot be used as arguments in demand functions without bringing in money. He rehabilitated the classical quantity theory along with its assumption of neutrality of money, by making the demand for goods depend upon relative prices.

The difference between the approaches of Keynes and Patinkin is that while Keynes rejected the classical quantity theory of money and its dichotomisation of the monetary and real sectors and attempted to integrate the two sectors (through rate of interest). Patinkin rejected the classical dichotomy and integrated the two sectors (through real-balance effect), but rehabilitated the quantity theory and thus remained in the classical tradition.

4. Real-Balance Effect:

Real-balance effect refers to the effect of a change in the value of real cash balances held by the public. Real balances are defined as M/P, where P is the price level and M is the outside money, i.e., money issued by the government or the central bank, who are not considered as a part of the public.

Since M is a liability of the government and asset of the holding public, M/P is a part of the real net wealth of the public and any change in it produces wealth effect.

If the value of real balances (M/P) increases, other things remaining the same, the public becomes wealthier than before and will be induced to consume more and save less out of a given level of real income.

This is the real- balance effect for consumption-saving decision. The real-balance effect was first introduced by Pigou to defend Say’s law of markets against Keynes’ attack and then used by Patinkin to integrate the monetary and real sectors and thereby to rehabilitate the classical quantity theory of money.

Criticism of Dichotomy between Monetary and Real Sectors:

The Classical quantity theory of money maintains a dichotomy between the monetary sector and the real sector. It assumes money as neutral and having no influence on output, which is governed by real variables like labour, capital and technology. An increase in the money supply raises the absolute price level without affecting relative prices which are determined in the real sector.

According to Patinkin, the dichotomy between the monetary and real sectors is neither necessary, nor valid, nor even consistent with the argument of the quantity theory of money. As he writes, “the truth of the matter is that not only is this dichotomy not necessary, not only is it not valid, but its basic assumption is even a direct denial of the quantity theory itself.”

According to Patinkin, the classical theory suffers from a logical error on the consideration of the dichotomy of the pricing process. Say’s law and the quantity theory of money, the two pillars of the classical economics, involve mutually incompatible assumptions; the former assumes interrelationship between the monetary sector and the real sector, whereas the latter assumes a dichotomy between the two sectors.

In a modem economy, goods are sold in the first instance for money. The supply schedule for each good constitutes a demand schedule for money and the demand schedule for each good constitutes a supply schedule for money. Say’s law (i.e., supply creates its own demand) implies that an excess supply of goods (or an excess demand for money) tends to be self-correcting. If there is an excess supply of goods (or an excess demand for money), then prices of goods must fall (or value of money must rise).

As a result, demand for goods (or supply of money) will increase until the excess supply in the commodity market (or excess demand in the money market) is eliminated. Thus, on this argument, absolute prices (i.e., value of money) are determined by the same set of forces as determine relative prices (prices of goods).

For every set of relative prices there is a corresponding unique absolute price level at which the money market will be in equilibrium. Thus, Say’s law does not dichotomise the pricing process; the monetary and the real sectors are interrelated.

In the cash-balance approach of the quantity theory of money, the dichotomy between the monetary and real sectors is maintained through its assumption of unitary elastic demand for money. Unitary elastic demand for money means that people want to hold given amounts of real balances and that a change in price level should not cause a real-balance effect.

In other words, when money is neutral, and there exists no money illusion, a change in price level does not lead to a non-proportionate change in demand for money balances. According to Patinkin, a change in P as a result of a change in M generates a real-balance effect and hence does not result in an equi-proportionate change in excess demand for money i.e., KPT – M, where KPT stands for the demand for money and M for supply of money.

In the words of Patinkin, a “Change in P alone generates a real-balance effect, hence a change in the planned volume of transactions, T and hence a non- proportionate change in the amount of money demanded, KPT. Thus, if, properly interpreted, the Cambridge function does not imply uniform unitary elasticity.”

Integration of Real and Monetary Sectors:

According to Patinkin, changes in money supply affects first the real balances and through real balances, relative prices, and through relative prices, absolute prices. Thus, while the quantity theory holds that money supply affects the absolute price level directly, leaving the relative prices unaffected, Patinkin believed that the money supply affects absolute prices through the real-balance effect.

Money is not merely a medium of exchange, it also has an asset value. The stock of money gets distributed as cash balances among the holders of money as an asset. A demand for money is a demand for cash balances, and a demand for cash balances is a demand for real balances, i.e., for what the cash balances can purchase.

In this way, an increase in the quantity of money first influences the demand for commodities and their relative prices through real-balance effect and then the absolute price level. Thus, Patinkin was able to integrate the monetary sector with the real sector through the real-balance effect.

Rehabilitation of Quantity Theory of Money:

Patinkin used the real – balance effect not only to eliminate the dichotomy between monetary and real sectors, but also to rehabilitate the classical quantity theory of money. There arises a contradiction. The quantity theory of money can be retained only on the condition of neutrality of money which means that changes in the quantity of money will influence the absolute price level and leave the relative prices and real variables unaffected.

This necessitates the bifurcation of the monetary sector from the real sector which Patinkin has already rejected and removed. The problem before Patinkin is how to retain both the integration of the two sectors and the quantity theory of money along with its assumption of neutrality of money?

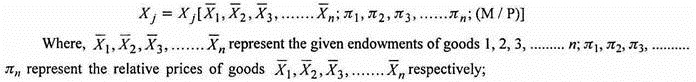

He solved this problem and rehabilitated the quantity theory by making the demand for goods a function of real balances held by the individuals. The demand function for good Xj will then be written as-

M stands for the money balances of the individuals under consideration; and

M/P stands for their real balances.

An increase in money balances (M) or a reduction in the price level (P) makes people spend more and push up prices till money balances no longer appear excessive.

Real-balance effect is the essential force through which equilibrium is established in the money market. If the prices fall below their equilibrium level, this will increase the real balances of the cash holders, increase their consumption expenditure and raise the prices back to their equilibrium level.

Similarly, if the prices rise above their equilibrium level, this will reduce the- real wealth of the cash holders, lead them to spend less, and thus, in turn, will bring the prices back to the equilibrium level.

To Sum Up:

Patinkin, by introducing real balances as a determining variable in demand functions for goods, was able- (a) to integrate the monetary sector and the real sector by ensuring that relative prices cannot be used as arguments in demand functions without bringing in money; and (b) to rehabilitate the classical quantity theory of money based on the assumption of neutrality of money by making demand for goods depend upon relative prices and not absolute prices.

Patinkin, in his book Money, Interest and Prices, attempted to integrate monetary and value theory through real balance effect. He maintained that existence of a real balance effect in the real sector integrates monetary and real economic analysis. When some form of real balance variable appears in the equations of the real sector model, separating real economic analysis from monetary economic analysis is not valid.

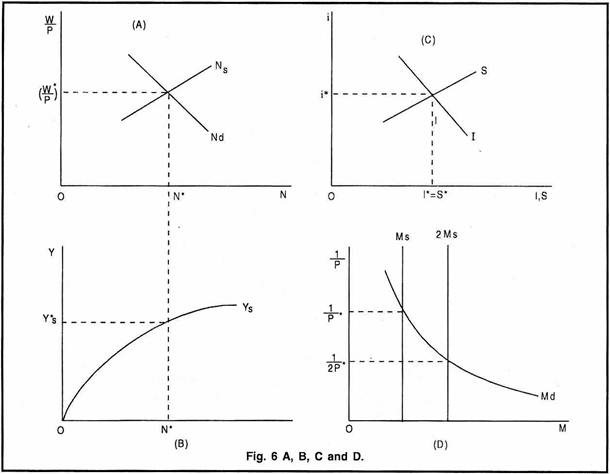

Integration of real and monetary sectors through real balance effect can be understood with the help of Patinkin’s general equilibrium model. In this model, we consider three markets: commodity market, labour market (both comprising real sector), and money market.

Patinkin’s system is based on the classical assumption that money is neutral. In other words, it assumes that- (a) all prices are flexible; (b) expectations are unit elastic; (c) no distribution effect exists; and (d) no money illusion exists in any of the functions. Moreover, it is also assumed that all money is of outside variety and no government debt exists.

Introduction of real balance variable in the real sector implies that- (a) consumption and investment expenditures of the individuals (C and I) are influenced not just by their current real income, but also by the real value of cash balances that they hold; (b) the transactions and precautionary demand for money (L1) depends not just on current real income, but also on the real value of the stock of liquid assets; (c) Liquidity preference (L) affects aggregate demand not just through investment via rate of interest, but also through consumption; and (d) real income is not determined independently of changes in money wages and prices. In short, the price level now enters decisively into every argument of income determination.

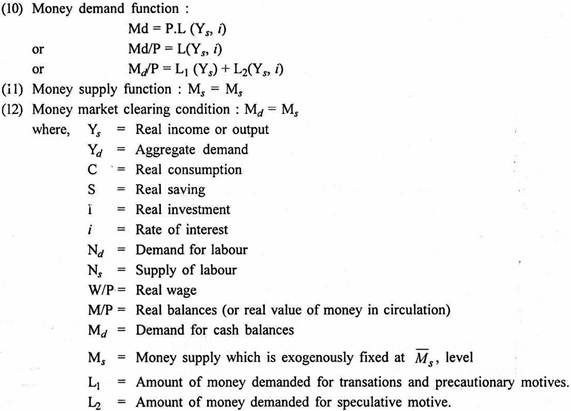

The general equilibrium model of income determination (including the real balance variable M/P) is given below:

Real Sector:

The real sector includes commodity market (Equation (1) to (6)) and labour market (Equations (7) to (9)).

Monetary Sector:

Equations (10) to (12) represent monetary sector.

The real sector of the above equational system contains nine equations and ten endogenous variables (Ys, Yd, C, S, I, i, Nd, Ns, W/P, M/P). Thus, we cannot determine the equilibrium values of the variables of the real sector. Such equilibrium values can be determined only when the three equations and two unknowns (Md, P) of the money market are added.

By integrating the two sectors, we obtain a completely determinate system of 12 equations and 12 unknowns. Thus, we conclude with Patinkin that when real balances variable (real outside money M/P) appears in the real sector, it is invalid to dichotomise the real sector from the monetary sector.

Effect of Change in Money Supply:

Patinkin deals with a typical classical situation in which- (a) money is neutral, i.e., a change in the money supply changes the nominal variables proportionately, while leaving the real variables unchanged; (b) strict version of the quantity theory of money operates, i.e., the change in prices is proportional to the change in money supply; and (c) dichotomisation is not valid, i.e., the real economic sector cannot be separated from the monetary sector.

Such a situation is possible if all money is outside money and there is no government debt. Truly, in classical times, money was mainly of fiat or commodity variety and therefore was of the outside type, and governments were not fiscally active. Patinkin was able to integrate the real sector and the monetary sector through his real balance effect.

He could maintain the neutrality of money under the neo-classical assumption of (a) flexibility of all prices, (b) unit-elastic expectations, (c) absence of distribution effect, and (d) absence of money illusion.

In order to understand the mechanism how the neutrality of money is maintained, we must analyse the effect of change in the quantity of money. Let us start with the initial equilibrium position when all prices, i.e., the commodity prices, the interest rate and the real wage rate are at their equilibrium levels P0, i0 and (W/P)o respectively.

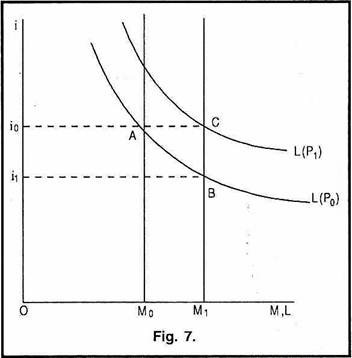

Now there is an increase in money supply which disturbs the initial equilibrium position. Figure-7 illustrates the impact of increase in money supply from M0 to M1.

In the initial stages, after the increase in the amount of money, the rate of interest will fall from i0 to i1, as the equilibrium in the money market moves from point A to point B. Only by such reduction in the interest rate the individuals will be induced to hold additional money supply. But, when the money supply increases, the price level also increases (from P0 to P1), because the excess supply in the money market implies excess demand in the commodity market, which results in raising prices.

When the price level increases, the demand schedule for money cannot remain unchanged because the demand for nominal money depends upon the price level. Thus, as a result of rise in price level from P0 to P1, the demand for money increases and the demand schedule for money shifts upward from L(P0) to L(P1).

The new equilibrium position in the money market is at point C, which indicates that the interest rate has risen again to its original level (i.e., from i1 to i0). Similarly, in the labour market, money wages and the prices increase in the same proportion, thus leaving the real wage rate at the initial equilibrium level (W/P)0.

Thus, under the neo-classical assumptions, changes in the money supply have no effect on the equilibrium values of real variables (including interest rate), and the equilibrium values of the nominal variables (prices and money wages) change in proportion to the change in the money supply. Hence money is neutral or money is veil.

Real – Balance Effect, Keynes Effect and Pigou Effect:

The real-balance effect comprises both the Keynes effect which causes shift in the LM curve and the Pigou effect that causes shift in the IS curve. Keynes, who otherwise believed that reduction in wages is neither theoretically sound nor practically desirable policy to increase employment, admitted that the wage reduction may have favourable effect on employment through its impact on interest rate.

Keynes effect, which considers the change in prices on demand for nominal money holdings, consists of a real-balance effect. Since the liquidity preference function shows the demand for real cash balances, a fall in prices reduces the liquidity preference in real terms which increases the demand for bonds and reduces the interest rate. In other words, Keynes effect implies that falling prices as a result of reduction in wages will shift the LM curve to the right.

Pigou, the chief defender of neo-classical economics, challenged the Keynesian under-employment thesis and attempted to show that, given the flexible wages and prices, an economy does automatically tend towards the full employment equilibrium level. Pigou’s argument, widely known as Pigou Effect, runs as follows. In depression, demand is deficient and, as a result, wages and prices fall and employment declines.

As prices fall, the real value of the money holdings of the individuals rises. They will actually buy more than they did before. This rise in demand will stimulate output and thus take the economy to the full employment level.

In short, Pigou effect consists of an asset (wealth- income) effect on consumption and applies to the outside money (gold, fiat money; etc.). It states that as wages and prices fall, the ratio of supply of liquid wealth to national income rises which stimulates consumption. In other words, Pigou effect implies that falling prices will shift the IS curve to the right.

From the above analysis, it is clear that both Keynes effect and Pigou effect contain real balance effect. Patinkin’s real – balance effect, which involves the influence of prices in every argument of income determination combines both Keynes effect and Pigou effect.

It states that falling wages and prices will shift both LM and IS curves to the right and this process of shift will continue until these curves intersect at the full employment equilibrium level.

Archibald and Lipsey, however, do not accept Patinkin’s formulation on the ground that the real – balance effect is only a short – term phenomenon and is irrelevant for the long-term equilibrium. Patinkin’s solution is helpful only in ensuring the stability of price level, but it does not provide a proper transmission mechanism through which real – balance effect can be shown to lead to a long – term neutrality of money.

Price stability and neutrality of money are two different things. Some kind of monetary effect is needed for price stability, but it does not have to be real-balance effect. The mere fact that people want to hold money and that the available quantity is fixed will ensure the stability of price level; but it will not produce the neutrality of money of the classical theory.