In this article we will discuss about the quantity theory of money by Cambridge, Keynes and Friedman, along with its criticisms.

1. Cambridge Cash-Balance Approach:

During almost the same period when Fisher was developing his equation of exchange in America, Marshall, Pigou, Robertson, Keynes, etc. at the Cambridge University popularised the classical Cambridge cash-balance approach to the quantity theory of money. While Fisher’s transactions approach emphasised the medium of exchange function of money, the cash-balance approach was based on the store of value function of money.

According to the cash-balance approach, the value of money is determined by the demand for and supply of money. This new approach, however, considers the demand for money and supply of money at a particular moment of time, rather than over a period of time as considered by the transactions approach. Since, the supply of money at a particular moment is fixed it is the demand for money which largely accounts for the changes in the price level. In this sense, the cash-balance approach is also called the demand theory of money.

The Cambridge economists viewed the term ‘demand for money’ in a different manner. The demand for money arises not because of transactions (as assumed in Fisher’s approach), but because of its being a store of value. The real demand for money comes from those who want to hold it for various motives and not from those who want to exchange it for goods and services.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This is the same thing as to say that the real demand for houses comes from those who want to live in them and not from those who simply want to construct and sell them. Thus, in the Cambridge approach, the demand for money implies demand for cash balances.

Cash balance is that proportion of the real income which the people desire to hold in the form of money. The total demand for money of the economy is a certain proportion of its annual real national income which the community wants to hold in the form of money. In the words of Marshall, “In every state of society, there is some fraction of their income which people find it worthwhile to keep it in the form of currency; it may be a fifth or a twentieth.”

When people increase their demand for money, it implies a fall in the demand for goods and services, because they can have larger cash balances only by cutting down their expenditure on goods and services. A fall in the demand for goods and services will reduce the price level and, consequently, the value of money will rise. Conversely, a decrease in the demand for money will raise the price level and hence, will reduce the value of money.

The Cambridge approach applies the general demand analysis to the special case of money. It inquiries into the utility of money, the nature of the budget constraint and the opportunity cost of holding money. People desire to keep money balances for transaction and precautionary motives.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Given the utility of money for transaction and precautionary motives, the amount of money to be held in by the individual is determined by his wealth and income forming the budget constraint. Within the absolute budget constraint, the actual proportion of wealth and income to be held in money form depends upon the opportunity cost of holding money, consisting of the rate of interest, the yield on real capital and the expected rate of inflation.

After recognising the importance of so many factors on the demand for holding money, the Cambridge economists, however, simplified the demand for money function by assuming the demand for money holding (Md) as a constant proportion (K) of money income (PY). Thus,

Md = KPY

Criticisms of Cash-Balance Approach:

Despite its superiority, the Cambridge approach also suffers from a number of drawbacks as discussed below:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Simple Truism:

Like the transaction equation, PT = MV, the Cambridge equation, M = KPY, is also simple truism. It merely establishes proportionate relationship between the quantity of money and the price level, assuming all other factors to be constant.

2. Unitary Elastic Demand:

The cash-balance approach is based on the assumption that demands for money has uniform unitary elasticity. It means that an increase in the desire for holding cash balance (K) leads to equi-proportionate fall in the price level. This is possible in a static society when stock of money and the volume of goods and services remain constant and not in dynamic conditions.

3. Speculative Motive Ignored:

The cash-balance theory has not properly analysed various motives for holding money. For example, it ignored the speculative demand for money which turned out to be an important determinant of holding money in Keynesian analysis. In fact, it is the speculative motive which causes violent changes in the demand for money.

4. Investment Goods Ignored:

A serious drawback in the Cambridge approach, particularly that given by Pigou and Keynes, is that it explains the value of money in terms of consumption goods and ignores the investment goods altogether. This is a narrow view of the purchasing power of money.

5. Role of Rate of Interest Ignored:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The theory neglects the role of rate of interest in explaining the changes in the price level. In fact, rate of interest has a definite influence on demand for money and, in turn, on the price level and a realist monetary theory can hardly ignore its importance.

6. Real Factors Ignored:

The theory, while explaining the changes in price level ignored the importance of real factors like, income, saving, investment, etc. on prices. These factors have determining influence on the price level of the economy.

7. Real-Balance Effect Ignored:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Like Fisherian approach, the Cambridge economists also assumed neutrality of money and a dichotomy between the money and the commodity markets and thus maintained that absolute prices are determined in the money market independently from the determination of relative prices in the commodity market.

Thus, it ignored the real-balance effect which implies that an individual’s wealth is influenced by the changes in money balances and the price level and the changes in wealth further influence the expenditure on goods.

8. Narrow View of K:

The theory presents a narrow approach by making real income as the sole determinant of K. It has overlooked the importance of other factors, such as, price level, banking and business habits of the people, business integration, etc., which may influence the value of K.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

9. Two-Way Relationship between K and P:

The theory maintains that the value of money or the price level (P) is determined by K. But it has been pointed out that K not only influences P but is also influenced by it. During rising prices (P), the proportion of money which people wish to hold (K) declines and vice versa.

10. K and T Assumed Constant:

Cambridge version, like Fisherian version, assumes K and T as given which is possible only in a static situation and not in dynamic conditions.

11. No Explanation of Trade Cycles:

The Cambridge approach like the transaction approach, provides no explanation for the trade cycle; that is, why prosperity leads to depression and depression leads to prosperity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

12. Lacks Quantitative Analysis:

The Cambridge approach does not provide an adequate monetary theory which can be used to explain how much prices and output will change as a result of a given change in the supply of money.

In spite of its various shortcomings, the Cambridge cash-balance approach is a definite improvement upon the Fisherian transaction approach. The great contribution of the Cambridge approach is the analysis of demand for money as an important determinant of value of money. It is this contribution which has opened a new horizon for the development of modem monetary theory.

2. Keynes’ Theory of Money and Prices:

The classical quantity theory of money maintains that there is a direct and proportionate relationship between the quantity of money and prices. In other words, if money supply is doubled, the price level will be doubled and the value of money will be halved and vice versa. The classical theory gives no explanation of the causal mechanism by which a change in the quantity of money leads to the change in the prices.

Keynes, in his General Theory (1936), criticised the classical theory and advocate the view that there is no direct, simple and predictable relationship between the quantity of money and its value or prices. Keynes provided the causal process by which changes in the quantity of money brings changes in the price level.

Keynes discards the classical theory of money on the following grounds:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) It is based on the unrealistic assumptions of full employment and the absence of money illusion.

(b) It unnecessarily assumes money as neutral and is based on a false division of the economy into the real and monetary sectors,

(c) It fails to integrate the monetary theory with the general theory of value.

(d) It fails to provide the causal process between money supply and the price level.

Indirect Relation between Money and Prices:

Keynes’ main contribution lies in shattering the false belief of the traditional economists that there exists a direct and proportionate relationship between the quantity of money and the level of prices. According to Keynes, the relationship between the quantity of money and the price level is neither direct nor proportionate.

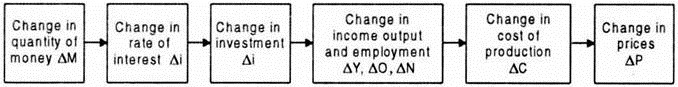

A change in the quantity of money may or may not affect prices. If it does, it will do so only indirectly and uncertainly. It all depends upon the effects of the change in the quantity of money on the aggregate spending and the elasticity of supply of goods and services. The impact of change in the supply of money on prices is seen via its impact on rate of interest, level of investment, output, employment and income. The causal process by which an increase in the quantity of money affects the prices is illustrated in the following chart –

Various steps in the causal process are as follows:

(i) Given the liquidity preference function, an increase in the supply of money reduces the rate of interest.

(ii) Given the marginal efficiency of capital, a fall in the rate of interest increases investment.

(iii) Given the marginal propensity to consume, an increase in investment will lead to a multiple increase in output, employment and income (through multiplier effect).

(iv) Increase in output increases demand for and prices of factors of production which raise the cost of production. The rise in the cost of production, in turn, raises the prices; prices rise because of the factors like the rise in labour costs, bottlenecks in production costs, etc.

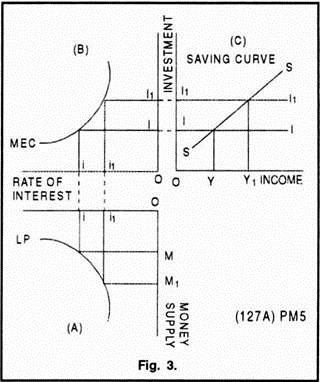

Figure 3 explains the indirect causal process between the change in prices as a result change in money supply. Figure 3-A shows that given the liquidity preference function (LP curve), as money supply increases from OM to OM1 rate of interest falls from Oi to Oi1. Figure 3-B shows that, given the marginal efficiency of capital (MEC curve), as the rate of interest falls from Oi to Oi1, investment increases from OI to OI1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Figure 3-C shows that given the saving function (SS curve) as investment increases from OI to OI1, income (and also output and employment) increases from OY to OY1. As a result of the increase in income, output and employment, the demand for factors of production and their prices will increase, cost of production will go up and the prices will rise.

Thus, Keynes integrates the theory of money and the theory of value or relative prices and the rate of interest is the link between the monetary sector and the real sector. The classical theory of money ignored the influence of the quantity of money on the rate of interest and thereby, on output, employment and income and then on relative prices. It assumes a direct relationship between die quantity of money and the level of absolute prices, relative prices remaining unaffected.

Reformulated Theory of Money:

Keynes not merely criticised the classical quantity theory of money but completely reformulated and generalised it. The substance of the reformulated theory is given in Keynes’ own words, “So long as there is unemployment, employment will change in the same proportion as quantity of money and when there is full employment, prices will change in the same proportion as the quantity of money.”

Thus, Keynes’ reformulated version has the following two possibilities:

(i) When there is unemployment of resources, an increase in the quantity of money increases output and employment in the same proportion as the quantity of money has increased and prices will remain unchanged.

(ii) Once the full employment level is reached, further increase in the quantity of money leads to a direct and proportionate increase in prices. It does not affect the real factors (output and employment). Keynes argued that real inflation starts only after full employment.

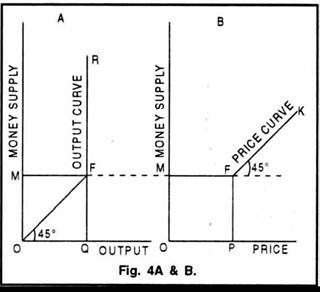

Figure 4-A & B illustrates the propositions of Keynes reformulated theory of money. In Figure 4-A, OFR is the output curve and point F shows full employment level. Before full employment, as quantity of money is increased (upto M), output Increases proportionately (upto Q). After full employment as quantity of money increases (after M), output does not increase at all (after Q, FR part of the output curve is vertical).

In Figure 4-B, PFK is the price curve and point F is the full employment level. Before full employment, as quantity of money is increased (upto M), prices do not increase at all (as PF part of the price curve is vertical). After full employment, as quantity of money is increased (after M), prices increase proportionately (as shown by FK part of price curve).

Assumptions:

Keynes’ reformulated theory of money is based on the following assumptions:

(i) So long as there is unemployment, the supply of all factors of production is perfectly elastic. It means that the supply of factors of production can be increased according to their demand.

(ii) So long as there is unemployment, the supply of output is unitary elastic. It means that there is equi-proportionate relationship between money and output.

(iii) When there is full employment of resources, the elasticity of supply of output in response to change in money supply is zero.

(iv) All unemployed factors of production are homogeneous, perfectly divisible and substitutable.

Price Rise before Full Employment:

Though a price rise has been considered a post-full-employment phenomenon, but Keynes also discusses a possibility of rise in prices before full-employment is reached. He pointed out that an increase in money supply may lead to a gradual rise in prices during the transition period even before the stage of full employment is reached. Such a kind of price rise before full- employment is not true inflation (which occurs only after full- employment) and is termed as semi-inflation or pre-full-employment inflation.

A rise in prices before full-employment occurs due to the following reasons:

1. Rise in Money Wages:

As the output increases, the demand for labour and employment also increases. This increases the bargaining power of the workers. As a result, wages rise, leading to a rise in the cost of production and prices.

2. Law of Diminishing Returns:

In the short run, when output expands with the given plant and technology, the law of diminishing returns or increasing costs start operating. This law increases the cost of production and prices.

3. Production Bottlenecks:

As the output increases in the economy, certain bottlenecks in the production process, such as shortage of raw materials, power shortage, lack of transport facilities, immobility of factors of production, etc., may appear. These bottlenecks raise the cost of production and hence prices.

4. Heterogeneity of Factors:

Heterogeneity of factors, particularly of labour units which differ in skill and efficiency, may also lead to a rise in the cost of production arid hence the prices.

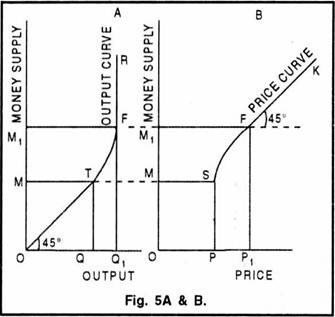

Figure 5 A and B shows the possibility of rise in prices before the level of full employment is reached. In Figure 5A, OTFR is the output curve and point F shows full-employment level. Initially, as the money supply increases (upto M), output increases proportionately (upto Q).

But, when money supply increases from OM to OM1, output curve (TF portion) becomes less elastic due to inelasticity of factors of production and bottlenecks in the production process and thus output increases slowly from OQ to OQ1. After full employment level, output curve (FR portion) becomes vertical and the increase in money supply (after M1) will not increase output at all (after Q1).

In Figure 5B, PSFK is the price curve and point F shows full- employment level. Initially, as the money supply increases upto M, prices do not increase at all (and remain at OP level). When money supply increases from OM to OM1, prices increase slowly from OP to OP1 due to the increase in the cost of production. After full-employment level, the increased money supply (after M1) will lead to a proportionate increase in prices (after P1).

Conclusions:

Keynes’ theory of money and prices is more general than the classical theory, because, whereas the classical economists consider the effect of an increased money supply in a special case of full employment.

Keynes’ theory of money applies to both full employment and less- than full-employment situations.

Main conclusions of Keynes’ theory are given below:

(i) There is no direct and proportionate relationship between money supply and the prices. Money supply influences the prices only indirectly via its effects on the rate of interest, the volume of investment and the level of output.

(ii) So long as there is unemployment of resources in the economy, employment and output will change in same proportion as the quantity of money; the price level will not change.

(iii) Once full employment is achieved, any increase in the money supply will lead to direct and proportionate increase in price level; output will not change at all. This shows that the classical quantity theory applies only under full-employment.

(iv) In reality, even before lull-employment, prices may rise due to inelasticity’s of factors of production and other bottlenecks in production.

(v) True inflation starts only after full-employment. Any price rise before full-employment is called semi-inflation.

Superiority of Keynes’ Theory of Money and Prices:

1. Analysis of Causal Process:

The classical economists establish a direct relationship, between money and prices, which is not supported by facts. Keynes, on the other hand, maintains that the relationship between money and prices is indirect and this indirect relationship is established through rate of interest and a chain of other factors like investment, income, output and employment and costs. Thus, Keynes explains the causal process between the change in money supply and the resultant change in prices.

2. Integration of Monetary Theory with Theory of Value:

Another merit of Keynes’ theory of money is that it integrates monetary theory with the theory of value. The classical economists separate the monetary theory from the theory of value; the former explains absolute prices, while the latter explains the relative prices. The quantity theory of money states that there exists a direct and proportionate relationship between the quantity of money and the level of prices; relative prices remain unchanged.

On the contrary, according to Keynes, the quantity of money, through its impact on the rate of interest, influences the output, which causes changes in the cost and, in turn, in the relative prices. Thus Keynes integrates the theory of money with the theory of value. And this integration is achieved through rate of interest which provides a link between the monetary sector and the real sector.

3. Integration of Monetary Theory with the Theory of Output:

Keynes also integrates the theory of money with the theory of output. In fact, the integration of monetary theory with the theory of value is achieved through the theory of output. An increase in the money supply reduces the rate of interest, which increases investment, which, in turn, will lead to an increase in output, employment and income. The increase in output and employment raises cost of production which ultimately raises prices.

4. No Assumption of Full-Employment:

The classical conclusion that all increases in the quantity of money tend to be inflationary is valid only under the assumption of full employment. Keynes, on other hand, rejected this assumption and observed that in reality there exists unemployment and full- employment is only an exception.

In fact, Keynes’ theory is more general because it analyses both full-employment and less than full-employment conditions. According to him, “So long as there is unemployment, employment will change in the same proportion as the quantity of money; and when there is full employment, prices will change in the same proportion as the quantity of money”.

5. Analysis of Inflation:

Keynes distinguishes between true inflation and semi-inflation. According to him, prices may rise even before full-employment level is reached. This is called semi-inflation which occurs due to the operation of the law of diminishing returns, increasing bargaining power of workers and the bottlenecks in the production process.

True inflation, on the other hand, starts only after the level of full- employment has been achieved. True inflation occurs because the elasticity of supply of output in response to changes in the money supply becomes zero. In other words, an increase in money supply does not increase output at all; only prices increase. It is the true inflation which is dangerous for an economy and is to be feared.

6. Policy Implications:

Keynes’ monetary theory serves as a guide for framing a suitable monetary policy during depression and boom period. He suggests a cheap money policy (increasing money supply and reducing the rate of interest) for depression and a dear money policy (controlling money supply and raising the rate of interest) for boom period.

Keynes, however, considers monetary policy to be less effective as compared to the fiscal policy, particularly during depression and unemployment condition. This is because during depression – (a) the liquidity preference function is elastic and insensitive to changes in money supply, and (b) the investment function is insensitive to change in the rate of interest due to depressed profit expectations.

Criticisms:

Keynes’ theory of money and prices has been criticised by the later economists like Patinkin, Friedman, etc., on the following grounds:

1. Friedman’s Criticism:

Contemporary quantity theorist, Friedman criticised Keynes for restricting the role of money in economic activity. Keynes’ theory of money assigns a passive role to money in explaining changes in income. Money influences income only indirectly through its effects on the rate of interest and investment.

Though changes in income from changes in investment can be predicted through a relatively stable multiplier, but changes in investment as a result of changes in money supply cannot be predicted because money has only an indirect and quite limited influence on investment.

According to Friedman, on the other hand, the empirical evidence suggests that the velocity of money is more stable than the investment multiplier, and thus a more stable relationship exists between changes in the quantity of money and changes in income. If this is so, then money becomes an important factor in the sense. That changes in income can be more accurately predicted from changes in the money supply than from the changes in investment.

2. Patinkin’s Criticism:

Don Patinkin criticised Keynes on the ground that while integrating the theory of money with the theory of value he ignored the real balance effect. Patinkin has shown that by taking into account the real balance effect, not only the theory of money and the theory value are integrated, but also the quantity theory of money is rehabilitated along with its assumption of neutrality of money. According to Patinkin, changes in money supply affect first the real balances and through real balances, relative prices and through relative prices, the absolute prices.

3. Unrealistic Causal Process:

Keynes’ explanation of the causal process assumes the constancy of the liquidity preference function, the marginal efficiency of capital function and the consumption function. In reality, it cannot be said with certainty that these functions will remain constant. This makes the causal relationship between the quantity of money and prices highly complex and uncertain.

4. Unrealistic Assumptions:

The theory is also based on the unrealistic assumptions of perfectly elastic supply of factors of production before full employment and perfectly inelastic supply of productive factors after full-employment. Moreover, the assumption that effective demand increases in the same proportion in which the supply of money increases is also not tenable.

5. Incomplete Analysis of Inflation:

The theory fails to provide a complete explanation of rise in prices before full-employment. In particular, it does not explain the inflationary tendencies in less developed nations like India.

3. Friedman’s Modern Quantity Theory of Money:

Despite the sweeping influence of the Keynesian revolution against the classical economic tradition during 1940’s, there remained a few defenders of classical economics and the quantity theory of money who concentrated at the University of the Chicago. During 1950’s, Milton Friedman took over the reins of the Chicago School and led to the development of the modern quantity theory of the money and the monetarist school.

Milton Friedman presented his most elegant and sophisticated version of the quantity theory of money in his paper, “The Quantity Theory of Money – A Restatement”, published in 1956, which he regards as an attempt, “to convey the flavor of the oral tradition” of the Chicago School. Friedman also admits his indebtedness to Keynes and owes a great debt to the Cambridge cash-balance approach in the development of his theory of money.

Basic Features of Friedman’s Theory:

The basic features of Friedman’s quantity theory of money are summarised below:

1. Wealth Theory of Demand for Money:

Friedman’s quantity theory of money is wealth theory of demand for money and not a theory of the price level, or of money income, or of output. In his view, money is “a durable consumer good held for the services it renders, and yielding a flow of services proportional to the stock.”

Money is no longer a ‘veil’ without any permanent influence on the real sector. It is a type of capital good which is held for the services it provides. Thus, money is demanded as an asset or capital and the theory of demand for money is a part of the capital or wealth theory.

2. Broader Concept of Money:

Friedman analyses the demand for money as a whole instead of examining it in terms of specific motives. He does not distinguish between active and idle balances as Keynes did. Rather money is regarded as rendering a variety of services because of the fact that it serves as a temporary abode for generalised purchasing power.

3. General Demand Analysis:

Friedman applies general demand analysis to the case of money. The ultimate wealth-holders are households who regard money as a durable consumer good. As such, the general demand theory for consumer goods can be applied to the demand for money.

As with the general theory of demand, Friedman assumes that the tastes and preferences of money-holders are constant over a long stretch of time and space. He also assumes that money is subject to the law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution, i.e., with the increase in the stock of money held, its marginal service yield tends to diminish relative to the yield of other assets.

4. Forms of Wealth:

Friedman uses a broader concept of wealth in his analysis of demand for money. For him wealth consists of anything which is capable of generating an income steam and as such includes all the conventional assets. This definition also includes human assets.

Friedman distinguishes five forms of assets in which wealth can be held:

(i) Money—defined as claims to commodity units that are generally accepted in payment of debts at a fixed nominal value.

(ii) Bonds—defined as a claim to a time stream of payments that are fixed in nominal units.

(iii) Equities—defined as a claim to a time stream of payments that are fixed in real units.

(iv) Physical Goods—such as inventories of producer and consumer goods.

(v) Human Capital.

5. Determinants of Demand for Money:

Broadly speaking, the demand for money is thought to depend on three major factors:

(a) Total wealth to be held in various forms of assets—the analogue of budget constraint in the consumer demand theory;

(b) Relative price of and return on one form of wealth as compared to the other forms; and

(c) Tastes and preferences of the wealth- holder.

Cost of holding cash balances is influenced by- (a) the rate of interest and (b) the expected rate of change in the price level. An increase in the rate of interest or the price level causes a decline in the cash balances and vice versa.

Friedman’s Demand-for-Money Function:

The demand function for money formulated by Friedman, is given below:

M = f (Y, w, P, rb, re, rc, u) …. (1)

where,

M = aggregate demand for money.

Y = total flow of income.

w = ratio of non-human to human wealth

p = general price level.

rb = bond yields, the market bond interest rate.

re = equity yields, the market interest rate of equities.

rc = the expected rate of change of prices of commodities.

u = utility determined variables which tend to influence tastes and preferences.

The demand function for money in Equation (1) is independent of the normal units used for measuring money variables. It indicates that the amount of money demanded changes proportionately to the changes in the unit in which prices and money income are expressed. The equation thus expresses the first degree homogeneous function of P and Y. Or, in other words, if price level and money increases to λ time their original level, demand for money also increases to λ times its original quantity. Thus, we can writes.

λM = F(λY, w, λP, rb, re, rc u) …. (2)

Modern Version of Quantity Theory of Money:

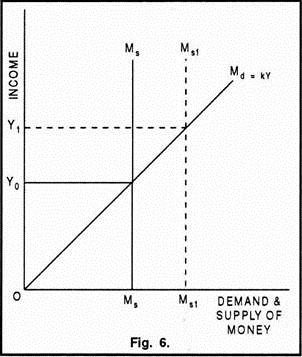

where v stands for income velocity.

Friedman thus maintains that a change in the stock of money leads to a change in the price level, or income or in both the variables in the same direction. The modern quantity theory of money states that as long as the demand for money is stable, a change in money supply causes a change in the price level; money supply also affects the real value of national income and economic activity but in the short run only. For Friedman, stability in the demand for money is a behavioural fact proved by evidence. As long as the demand for money is stable, it is possible to predict the effects of changes in money supply on total expenditure and income.

Friedman leads the monetarist school which maintains that if there is less-than-full employment, an increase in money supply will lead to a rise in output and employment because of a rise in expenditure. But this will happen only in the short run; soon the economy will return to the less-than-full employment level caused by other real factors. The monetarists believe that changes in money supply cannot affect real variables in the long run. At full employment level, an increase in money supply will raise prices.

Before full employment, income (Y) rises with a rise in money supply (M) and expenditure. This rise in income crucially depends upon the ratio of income to money supply (i. e., Y/M or velocity). Income will continue to rise until it has reached a limit where it achieves its previous ratio to money supply (Y/M) because at that point, output cannot be increased farther. People will raise their demand for money rather than spend it and the demand for and supply of money will once again become equal.

Significance of Modern Quantity Theory of Money:

Important implications of the modern quantity theory of money as propounded by Friedman are presented below:

1. Stable Demand Function:

The quantity theorists accept the empirical hypothesis that the demand for money is highly stable – even more stable than the functions like the consumption functions. According to Friedman, a stable function does not mean a constant velocity, but that the function is stable in terms of the variables which determine its value. Thus, an increase in velocity during inflation is consistent with functional stability.

2. Key Role of Price Level:

Monetarists regard price level as the single most important variable in the demand function of money. Price level provides and explains the link between money and inflation. Price level, which is the reciprocal of the value of money, plays an important role in bringing the demand and supply of money into balance.

3. Explanation of Changes in Income Velocity:

According to Friedman, cyclical movements in the income velocity are attributable to cyclical movements in current income relative to permanent income (i.e., expected trend of future income) and not the cyclical movements in interest as Keynesians believe. During prosperity, the demand for money rises proportionately with permanent income but less than proportionately with a rise in current income because permanent income rises less than current income in business expansion.

This implies that income velocity rises in prosperity because income velocity is defined as a current income concept. Similarly, during depression, permanent income and the demand for money fall proportionately in relation to each other but less than proportionately in relation to current income and income velocity falls.

4. Importance of Expected Inflation:

Expected rate of inflation is another important variable affecting the demand for money (inversely) in cases of rapid inflation. The monetarists, under the influence of Friedman, have analysed hyperinflations and the stability of the monetary system based on the effects of expected inflation on demand for money.

5. Low Interest Elasticity of Demand for Money:

Friedman and the monetarists regard the rate of interest as having very little influence on the demand for money.

6. Role of Monetary Policy:

The recent debate between the monetarists and the Keynesians centres round the question of changing aggregate demand by monetary policy or fiscal policy. According to the monetarists, given the stability in the demand for money, the monetary authority can control the aggregate spending by controlling the money supply.

The stabilisation policy should concentrate on monetary policy. The Keynesians, on the contrary, point out those only fiscal policies can change the level of income by changing aggregate demand. The monetarist argument assumes interest-inelastic demand for money, whereas the Keynesians assume a very low interest elasticity of the investment function.

7. Factors Affecting Supply of Money:

The quantity theorists maintain that there are important factors affecting the supply of money and they do not affect the demand for money. The view that the supply of money expands or contracts according to the needs of trade is rejected by the quantity theorists.

To Sum Up:

(a) Friedman can be viewed as being in the Cambridge tradition and as a formulator of a capital theory of demand for money,

(b) The difference between Friedman and the Keynesians regarding the demand for money shrinks considerably when we view the results of empirical studies. The studies have found permanent income and the actual rate of interest and not the rate of change in the price level, as explaining most of the variations in the demand for money,

(c) However, basic differences between the monetarists and the Keynesians, such as regarding the neutrality of money and the mechanism through which money affects the real variables still remains.