Read this article to learn about the monetarist reformulation and counter revolution of quantity theory of money.

Demand for Money—Genesis of Monetarism:

More fundamental and basic development in monetary theory has been the formulation of the quantity theory of money in a way much influenced by the Keynesian liquidity preference analysis.

However, the new approach emphasizes money as an asset that can be compared with other assets—it lays emphasis on the ‘portfolio’ analysis.

It is an analysis of the structure of people’s balance sheets; of the kinds of assets they want to hold renders the ‘Monetary Theory’ a part of the ‘Capital Theory’ or the ‘Theory of Wealth.’

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is very vital to understand that the treatment of money as an asset has gone in two different directions. On the one hand, it has led to an emphasis on near moneys—as an alternative source of liquidity embodied in the work of Gurley-Shaw and their analysis of financial intermediaries in providing money substitutes. The other direction in which the emphasis on money as an asset has led to is towards the development of a theory of the demand for money along the same lines as the theory of the demand for other assets and for commodities and services.

In such a theory, one asks what determines the amount of cash balances that people want to hold. Here it is proper to distinguish between cash balances in two senses—nominal cash balances i.e., nominal quantity of money as defined in terms of monetary units such as rupees and the real cash balances—the real stock of money as defined in terms of command over goods and services. Thus, in modern version particularly when we talk about the demand for money, we must be talking about the demand for real balances in the sense of command over goods and services and not about nominal balances.

In the theory of demand as it has been developed, the key variables include first, wealth or some counterpart of wealth. The second set of variables that is important is the rates of return on substitute forms of holding money. Here the most important thing that has happened has been a tendency to move away from the division of assets, not only into bonds but also into equities and real assets.

The relevant variables, therefore, are the expected rate of return on bonds, the expected rate of return on equities, and the expected rate of return on real property and each of these may, of course, be multiplied by considering different specific assets of each type. A major component of the expected rate of return on real property is the rate of change in prices.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to more recent emphasis, money is something more basic than a medium of transactions; it is something which enables people to separate the act of purchase from the act of sale. From this point of view, the role of money is to serve as a temporary abode of purchasing power. It is this view that is fostered by considering money as an asset or a part of wealth. Like the theory of consumer choice, the demand for money depends upon the total wealth held in different forms; prices of and return on one form of wealth and its alternative forms; tastes and preferences of wealth owing units.

Looked at in this way, it is plausible to think that there will be a more indirect and complicated process of adjustment to a change in the stock of money. Suppose there is a change in the stock of money—it leads to change in balance sheet—it leads to adjustment of balance sheets on the part of people—people will purchase other assets in the process—prices of assets undergo a change—this leads to further expansion of and change in the composition of assets—as prices of assets change— relative price of assets and flows also change. Thus, this information of monetary theory with its emphasis on monetary theory as a branch of the theory of wealth has important implications for the process of adjustment and for the problem of time lags.

For well over 200 years in economic literature, the quantity of money has been singled out for special attention, reflecting the common belief that money, prices and economic activities are in some way linked. Theories have varied from the supposition that a rigid relation existed between the quantity of money and the value of transactions which it could support—as if money were an intermediate product employed with a fixed technical co-efficient in the production of final output— through the hypothesis that the level of money income was the dominant, though not the sole, influence on the quantity of money required, to the belief the money is at best regarded as one amongst a number of alternative ways of holding wealth and that its demand is determined by its relative yield and other attributes.

The fixed technical co-efficient theory is the basis of the most rigid version of the quantity theory: the income theory lies behind the less rigid Cambridge version of this theory— which was elaborated and extended by Keynes—and the ‘asset theory’ is the foundation of the modern quantity theory of money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, we find that the modern quantity theorists treat the demand for money in just the same way as the demand for any other financial or physical asset. In consumption theory, the demand for a good is determined by its attributes including its price in relation to other goods—the purchaser’s set of choices being subject to income constraint. Similarly, in asset theory the demand for any particular asset is determined by its characteristics including its yield in relation to that of other assets—the asset holder’s set of choices being subject to a wealth constraint.

It is necessary that the precise nature of income or wealth constraint must be specified in some detail. The problems encountered in specifying the demand function for money (including financial assets) or demand function for financial assets (including money) are no different in their fundamental nature from the problems of consumer demand analysis.

Modern Version of Milton Friedman—Basis of Monetarism:

The differences between orthodox Keynesian Model, Radcliffe Model and Modern Quantity Theory of Money as presented by Milton Friedman can be traced in terms of their implications for the behaviour of the ‘velocity’ of money. Milton Friedman has given a new and reformulated model of the quantity theory of money so that it may command greater respectability, as the general approach based on MV = PT fell into disrepute after the crash of 1929.

It came into its own after the desperate attempts of certain monetary economists of Europe and America succeeded in rehabilitating the same. The contribution of the school lies chiefly in making the demand function for money more broad- based. It was only in 1956 that the theory was reformulated by Milton Friedman. He was supported by Simons Mints, Knight and Viner.

The modern quantity theory of money, as restated by Friedman, is primarily a theory of demand for money and not as in the classical version, a theory of the level of prices, or of money income or of output, no longer is money a ‘veil’ without any permanent influence on the ‘real sector’. He uses the modern theory to explain major depression as well as inflation. His greatest contribution lies in accepting variations in velocity as consistent with the quantity theory.

Unlike Fisher, Friedman does not view velocity as an institutional datum nor as a numerical constant, but rather as a functional relationship in which the demand for money is a function of a number of variables within the system, such as interest rate (its structure and types), income, wealth and expected changes in the price level. Depending on movements of these variables, velocity may vary both cyclically and secularly.

The central points in the restatement are that the quantity theory is a theory of the demand for money and not of income or prices, so that money is an asset or capital goods, so that the demand for it is a problem in capital theory. In formulating the demand for money as a form of capital, however, Friedman differs from the Keynesian theorists in starting from the fundamentals of capital theory. He begins from the broad concepts of wealth as comprising all sources of income, including human beings and relates the demand for money to total wealth and the expected future streams of money income obtainable by holding wealth in alternative form.

Thus, by a series of mathematical simplifications, approximations of non-observables, variables, simplifying economic assumptions and rearrangements of variables, he arrives at a demand function for money which depends upon the price level, bond and equity yields, the rate of change of the price level, income, the ratio of non-human to human wealth, etc.

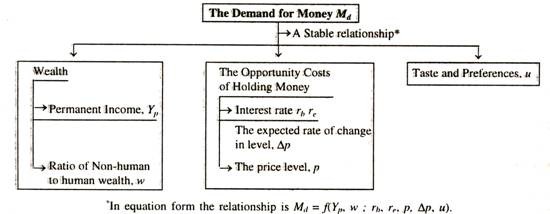

Friedman identifies three major determinants of the amount of money that households and business firms would like to hold at any given time.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These are:

(i) The total wealth in all forms of the households or business firms;

(ii) The opportunity cost of holding money;

(iii) The tastes and preferences of the wealth holding unit. Money in his analysis is viewed like any other commodity or good which yields some utility through its possession. Consequently, the gain—or utility—to be gotten from its possession has to be balanced against the utility foregone by not holding other forms of wealth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The table shows in a systematic form a formal structure of the Friedmanian variables that determine the demand for money.

The meaning of these variables are:

(i) Md = the demand for money balances. Monetarists view the demand for money balances as ultimately a demand for real balances, which means that nominal balances must be adjusted for changes in the price level.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Yp = Money income in Professor Friedman’s permanent sense,

(iii) w = The ratio of non-human wealth to human wealth,

(iv) rb = The rate of return on bonds,

(v) re = The rate of return on equities,

(vi) p = The general price level,

(vii) ∆p = The expected change in price level,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(vi) u = The tastes and preferences of the wealth holding units,

Milton Friedman (1956) argues that money can be regarded as one of five broad ways of holding wealth—money bonds, bonds, equities, physical goods and human wealth. Each of these has distinctive characteristics and each offers some return in money or in kind.

The yield on money is mainly in kind—although some forms of money e.g., saving deposits in banks, also have an explicit money yield. The real as opposed to nominal yield on money depends on the movements in the price level. If the price level falls, money appreciates and shows a capital gain in real terms which must be added to the nominal yield, while in the more common condition of rising prices a real capital loss has to be deducted from the nominal yield.

Bonds stand for assets which promise a perpetual income stream of constant amount. Like money, their real return is affected by changes in the price level, but it is also affected by changes in the rate of interest on bonds. If the rate of interest on bonds is rb, the nominal rate of return can be approximated by rb—(1/rb) drb/dt, where (Mrb) drb/dt measures the rate of capital appreciation due to changes in the rate of interest.

Equities stand for assets which promise a perpetual income stream of constant real amount. If the rate of interest on equities is re i.e., £1 of equities can be expected to yield annually the sum of £ re if prices are stable, the nominal rate of return is affected both by changes in this rate of interest and by changes in the price level. The associated changes in the capital value can be approximated by re—(1/re) dre/dt and (1/P) dP/dt respectively, so the nominal rate of return must also take account of the price level P.

Physical goods yield an income in kind which can seldom be measured by an explicit rate of interest. Their nominal rate of return is, however, also affected by the rate of exchange of the price level (1 /P) dP/dt which can be considered explicitly. Human wealth is the discounted value of the expected stream of earned income. It presents a problem because it can be substituted only to a very limited extent with other forms of asset holding.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Nevertheless, some substitution is possible ; people can sell assets in order to pay for training which will increase their future earnings, and their expected earnings also influence, the amount which they can borrow and hence their gross asset holdings. In principle, the limitations on substitutability make a case for distinguishing between human and non- human wealth in the demand function, which can be done by including in it the ratio of non-human to human wealth, w.

Finally, the wealth constraint must enter the demand function. In the absence of direct estimates of wealth, including human wealth, an indirect estimate must be used. Friedman makes use of permanent income Yp—a weighted average of current and past values of income—as an indicator. Some other investigators have confined the constraint to non-human wealth, W. This adds up to a formidable list of factors which should enter into the demand function for money.

However, for empirical work further simplifications must be made. If we keep in mind the Keynesian analysis of the speculative demand for money, we should note that the relevant capital gains on bonds and equities are not simply those which take place in practice but those which are expected to take place.

No measure of expected gains or losses due to changes in interest rates is available, so these terms are usually dropped from the demand function. The rate of change of prices has also usually been omitted, except in studies of hyper-inflation, and the ratio of non-human to human wealth has seldom been included. Finally, for statistical measures investigators have usually had to be content with employing one rate of interest as an indicator instead of including the yields on a variety of financial assets simultaneously. With these simplifications the demand function can be written as M = f (P, r, Yp, U) with W substituted for Yp, in some instances in the simplified form.

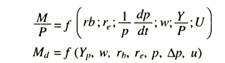

Friedman’s demand for money function can be shown as:

where rb is the market bond interest rate, re as the market equity rate of interest, 1/rb is the price of bond promising to pay a fixed income per year and 1/re is the price of equity promising to pay a fixed income per year, w as the ratio of non-human to human wealth and u as the objective factors in influencing tastes of ultimate wealth owning units and business enterprises. His is a significant contribution in adding these new variables and splitting the old ones. However, the most important is the inclusion of the variable 1/p dp/dt as showing the expected price level change of one unit of wealth (say one dollar).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It was this influence of price level expectations and changes thereof on asset prices that was generally neglected by Keynesian writers and here for the first time it receives an explicit recognition.

Professor Friedman holds that the above variables which determine the amount of money that people want to hold do not change much in the short run and secondly, he holds that the relationship between the demand for money balances and these key determinants is highly stable. The total wealth in all forms enters into the demand for money function because it represents the upper limit to the amount of money that can be held.

In other words, no one can hold more money than the total of the individual’s defined wealth in all forms. His concept of wealth includes more than just assets like cash, bonds, equities, etc. He includes in wealth various types of tangible capital (like producer and consumer durable goods) and human capital. He regards wealth as a factor that clearly overshadows all other determinants.

One may ask why has he included in the analysis a variable w representing the ratio of non-human to human wealth? Since we do not provide a market for human capital that would establish a rate of return on such capital, there is no simple way in which you can include in the analysis a variable that represents any direct measurement of human wealth. But the individual has some opportunity through education and training to substitute human capital for non-human capital and (vice versa) in his total stock of personal wealth.

Since this process takes place with a considerable lapse of time, therefore, in the short run the ratio of w will be relatively stable.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Friedman’s analysis, the cost of holding money is two folds:

(a) The rate of interest that could be obtained if bonds or equities were held instead of money; and

(b) The effect of changes in the price level of nominal money balances.

The underlying theoretical relationship is inverse, which is to say that when the cost of holding money rises less will be held and when it falls more will be held. Professor Friedman and his other monetarist colleagues do not deny that interest rates have an influence on the amount of money held, but unlike the Keynesians they maintain that the effect is relatively small. Similarly, an expected increase in the price level has the effect of making it more costly to hold money, since both the real value of money balances will be lessened and the market value of other assets will rise.

Thus, there will be a smaller demand for nominal money balances and the reverse would happen if the price level was expected to fall. According to Friedman, the tastes and preferences (u) of wealth owing units……… must in general simply be taken for granted in determining the form of the demand function………. and it will generally have to be supposed that tastes are constant over significant periods of time and space. Thus, Professor Friedman’s theory of the demand for nominal money balances can be reduced to the proposition that there are really four major determinants of this demand.

These are:

(i) Wealth or permanent income;

(ii) The price level;

(iii) A rate of interest;

(iv) A rate of increase in the price level.

In its most elementary form, his theory holds that the demand for money varies directly with the first two and inversely with the latter two. If we change his theory into a demand for real balances, it will mean, in effect, that this demand varies positively, with wealth (permanent income) and inversely with the cost of holding money (interest and expected rates of inflation).

The main difference between these demand functions and that derived from the Keynesian approach is the former’s emphasis on wealth as opposed to current income, and the omission of any unstable element, such as is implied by the speculative demand for money. The latter is not ruled out in theory—interest rate expectations appear in a free specification of the demand function but it has not been included in practice.

Finally, there is nothing in the ‘asset approach’ to suggest that the elasticity of demand for money with respect to the rate of interest will become infinite at some positive rate of interest. Friedman’s application to monetary theory of the basic principle of capital theory that income is the yield on capital and capital the present value of income, is probably the most important development in monetary theory since Keynes ‘General Theory’.

Its theoretical significance lies in the conceptual integration of wealth and income as influences on behaviour. The most important implication of Friedman’s analysis, however, concerns not the formation of monetary theory but the nature of the concept of income relevant to monetary analysis, which should correspond to the notions of expected yield on wealth rather than the conventions of national income accounting.

Mechanism of Monetarism (Structure of Monetarist Theory and Difference between Monetarism and Keynesians):

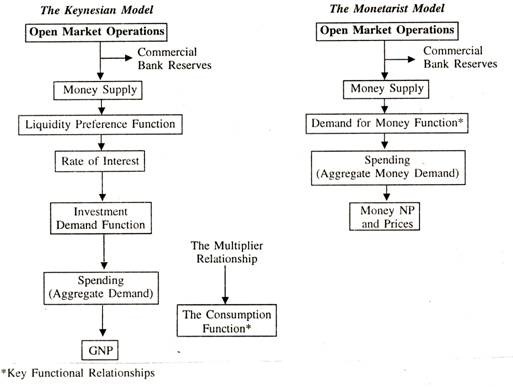

There are conflicting views of the mechanism as to how money supply affects the general economic activities or income level. On the one hand, some theorists put the emphasis on a direct relation between the money supply and expenditure. On the other hand, there are some who argue that it is by changing financial conditions particularly the rates of interest, volumes of lending and borrowing—that the influence of money supply on economic activities can be judged.

According to the former school, an increase in the money supply means that some money holders will have excess money balance in their asset portfolios. In the process of restoring equilibrium these balances will be converted into the real goods and services either directly or through the intermediation of financial institutions.

The pressure of demand for more goods and services will stimulate output and encourage price rises until the value of the output has risen in proportion to the increase in the money supply. This school is called the ‘monetary school’ and gives no special emphasis on the rates of interest on the financial assets. The other school points out that the increase in money supply will affect the rate of interest and emphasize that a change in the money supply will affect cost and the availability of the credit.

A fall in the rate charged to borrowers may stimulate consumption and investment directly, or a general easing in financial conditions following a rise in money supply may encourage financial institutions to make funds more readily available to potential borrowers. The superiority of ‘monetary’ over ‘Keynesian’ models has not been demonstrated. However, monetary factors are not unimportant; there is no reason to reject the view that changes in the money supply will affect income either directly or indirectly via changes in interest rates or the availability of credit.

Advocates of monetary approach have not yet shown that the changes in money supply have a reliable and predictable effect on expenditure, even the direction of causation between the money supply and income is at issue. In fact, we need not give to the money supply any special significance in the financial mechanism, we need not attribute to it any special direct causal influence on economic activity, and we need not believe that the monetary authorities adopt any very simple mechanism for its control.

Nevertheless, it is also obvious that we cannot dismiss the money supply and other financial factors as unimportant in the determination of economic activity; rather it is to be understood that interest rates and the supply of credit may have a considerable impact on economic activity and that the monetary authorities have the ability to control these variables.

The Monetarist Position (Mechanism):

Historically monetarists were concerned with the relationship between quantity of money and prices. But the modern quantity theorists or Monetarists—no longer believe changes in the money supply only affect the price level. The role of money, they find is much broader, as it is the crucial determinant of GNP. There is a direct and reliable link between the money supply and GNP.

Changes in the money supply can do the whole job and stabilization policy should concentrate on that and that alone. No wonder monetarists blame that Federal Reserve whenever anything goes wrong. The best- known position of the monetarists is that the movements of money supply have a big influence on economic activity and that fiscal policy has a much smaller role and effect than is commonly supposed. Their contribution lies in relating the effect of demand management (monetary instruments) of any kind to output, prices and employment.

They contend that changes in the money supply are the single and most important factor in the determination of the level of real output, employment and prices. Essentially, they argue that there is a direct link between money and the level of economic activities (GNP). According to the monetarists, emphasis should be shifted from the various Keynesian components of aggregate demand (C + I + G) to the demand for money.

They argue that there is a stable and predictable relationship between the amount of money people wish to hold and the level of national output. They hold that the proportion of national output over which people wish to keep command in money form is constant. They feel that k is stable or that velocity (V) is stable.

For example, if the level of money national income (Y/P,P) society wishes to hold money balances worth Rs. 100 crore. Again, suppose the actual supply of money is Rs. 100 crore.

The equilibrium prevails because:

Let the money supply increases by Rs. 50 crores. People are now forced to hold Rs. 150 crore. (Even though the national income is Rs. 600 crore and they wish to hold Rs. 100 crore). Since society is now forced to hold Rs. 150 crore and they wish it to be 1/6 of national income, it then follows that national income must rise to Rs. 900 crore because 1/6 of Rs. 900 crore is Rs. 150 crore. Equilibrium can only be established when the amount of money held is 1/6 of national income.

The monetarists are also critical of the adjustment process mechanism of fiscal policy. For example, if a deficit is created in an attempt to stimulate the economy, the monetarists argue that such a policy will not be successful unless it is accompanied by an increase in the supply of money.

An increase in G will initially cause the Y to rise but the increase in Y, given k will cause people to choose to hold higher levels of cash balances, for which they may have to decrease their consumption expenditures. As a result, there will be a decrease in private spending which will just balance the increase in G. The equilibrium level of national income will not change and the fiscal policy, as a result is rendered useless. According to monetarists, the transmission or adjustment mechanism of monetary policy is also based on asset portfolio adjustment.

Monetarists define the physical wealth of the economy to include not only real assets held by firms but consumer durables held by households. Since all wealth yields rates of return, monetarists argue that changes in the money supply will affect the real asset holdings of households in the same way that they affect changes in the real asset holdings of firms. Thus, the effects of monetary policy are more widely diffused than believed by the finalists. Monetary policy changes interest rates, which in turn, change rates of return and prices. This leads both households and firms to adjust both financial and real asset holdings until the desired composition of asset holdings are achieved.

Changes in rates of return and prices cause portfolio adjustments to occur until the actual and desired stocks are again equal. These adjustments directly affect the level of output demand prices and income because monetary policy directly influences investment expenditures as well as consumer durable expenditures.

Monetarists argue that both C and I type of expenditures depend on interest rate, these expenditures are highly interest elastic so that IS schedule is highly interest elastic. They further argue that since the demand for and supply of money is highly interest inelastic, the LM schedule is also highly interest inelastic. Thus, the monetary policy (shifts in the LM schedule) is the most important means whereby output demand can be changed. Fiscal policy (shifts in IS schedule) plays minor role, that is, ‘money, mostly matters’.

Again, the monetarists argue, that the appropriate time period of economic stabilization is the long-run and their theory is designed to explain the long-run phenomenon. Most of the exogenous shocks to the system stressed by the fiscalists are mild and their impacts are of such short duration that the economy is essentially stable in nature. Stability is ensured by market forces which change prices and rates of return in response to these exogenous shocks.

Although market imperfections may influence time patterns of response amongst economic variables and may cause inefficient allocation of resources, they do not affect, after all, the stabilizing function of market. Monetarists believe that the major impact of monetary policy is in the long-run because in the long period changes in factors, such as, labour force, capital stock, raw materials and technical progress account for major changes in real economic variables

Monetarists believe that we have come a long way from the view that money does not matter to the view that money matters a great deal and still to the view held by some that money alone matters. According to Friedman, changes in government expenditures and taxes have no visible effect on the economy, and hence the multiplier is non-existent. Gone, too, are such fiscal policy devices as the investment tax credit and accelerated depreciation allowances. The argument is clear—they contend—control the stock of money and you control the economy—control the stock of money by determining in advance how fast it should increase, and give the monetary authorities a rule to follow.

It may be true that money was under emphasized in the Keynesian model, but economists like Tobin, Samuelson, Solow etc. express doubts over the mechanisms that would make only money matter. It is not clear, they argue, how M or ∆M will cause a change in national product, nor it is clear what will happen to cost push inflation, because Friedman’s analysis permits only demand pull. The ∆M cannot affect the rate of interest, therefore, the other variables and hence income; that was ruled out.

The statistical evidence merely shows that there is some association between M and Y, but causation is not automatically established. Thus, Friedman’s theory of the role of money supply in the economic model is not convincing too many—the proposition cannot be discarded but neither can it be accepted.

It is easy to say—control the stock of money by giving monetary authorities a rule to follow but such a rule will be broken as soon as it is realized that some discretionary action is preferable— also serious doubts have been raised over whether or not the central bank of a country is capable of controlling the money supply so precisely.

The monetarists position has not changed from the one described above and disagreement still exists between monetarists and Post-Keynesians on the definition of money, appropriate concept of income and wealth, the degree of price and wage flexibility, the role of expectations, the degree of resource utilization and the influence of market imperfections.

The Fiscalist Position (Mechanism):

Keynesians, however, place major emphasis on the influence of fiscal policy, on the components of aggregate demand (C + I + G). They refute the arguments of the monetarists by saying that the economy is more complex than the monetarists seem to believe. Some changes in aggregate demand, they contend, are caused due to strikes and changing expectations or events about future. They argue that k and, therefore, V is not stable and as such the monetarist model is subject to much error in prediction. Keynesian argue that aggregate demand is much more stable than velocity, that is, multiplier is more stable than the velocity of money.

As a result, a Keynesian model is a better predictor of the level of economic activity than a monetarist model. Fiscalist argue that tangible real investment is highly interest inelastic so that IS schedule is highly interest inelastic. They also argue that since non- money financial assets are so close substitutes of money, changes in the interest rates on non-money financial assets change the quantity of money demanded by relatively larger amounts. This means that the LM schedule is very interest elastic.

Thus, fiscal policy (shifts in the IS schedule) plays the most important role in changing output demand. Monetary policy (shifts in the LM schedule) plays a relatively minor role, that is ‘money matters hut very little.’ Moreover, fiscalists argue that the appropriate time period of stabilization is the short-run.

Changes in thriftiness, inventions, bursts in investment, wars, droughts, strikes, changes in preferences and expectations, all go to make the economy essentially unstable, thus, short-run discretionary fiscal policies become quite appropriate The fiscalists argue that economic welfare of the society will be greatly impaired if short-run actions are not taken. They argue that since fiscal policies are more powerful and immediate than monetary policy—which is weak and slow—fiscal policies are preferred to monetary policies as a means of demand management and economic stabilization.

The main difference between the monetarists and Keynesians is essentially over the working of the monetary mechanism or the transmission process by which a change in the money supply causes a change in the level of income. Keynes perceived a substitution effect among money, financial assets and real assets. Assuming, in a broad sense, that there is a rate of return on all assets, in that all these assets provide their owners with benefits and further assuming that people are satisfied with their holdings of existing money balances—an increase in the supply of money would cause them to spend their additional money on financial assets.

Money will be traded or substituted for financial assets and this process of trading or substituting money for other financial assets will be carried to the point, at which owners find no advantage in further trading or substitution of this kind. This forces down, according to Keynesians, the interest rates and results in an increase in investment expenditure, causing a rise in income by way of multiplier. The wealth holders tend to substitute financial assets for excess money supply in the initial stages, they will sooner or later also substitute real assets for financial assets, thereby increasing the demand for real assets.

An increase in the supply of money will bring about a series of substitutions in portfolios which when completed will mean an increase in holdings of such assets as consumer durable goods as well as of other real assets and financial assets. Increased demand of these real assets will mean higher prices which will stimulate production of more goods and investment. The substitution into real assets must be the result of the fact that the yields on financial assets have fallen relative to the expected yields on real assets.

This proposition is fundamental because according to some economists, it constitutes the heart of the difference between the Keynesians and the Monetarists. Although monetarists also trace the effect of changes in money supply through a portfolio adjustment process much like that described above, they do not hold that changes in interest rate are a prerequisite to changes in the demand for goods and services or the demand for real assets.

Monetarists contend that following an increase in the money supply, there can be a portfolio adjustment involving a movement out of money directly into goods and services or assets. The end result need not be a change in interest rates at all; it may be a change in the general price level or in output. Just as an increased amount of water may flow through a lake without raising its level (except momentarily), similarly, an increase in the money supply can lead directly to spending for real assets.

In other words, monetarists do not accept the Keynesian view of the adjustment process that increased money supply will lead to increased spending only indirectly by changing interest rates or by changing yields on financial assets or profitability of acquiring real assets. It is one thing for the monetarists to reject the Keynesian explanation, it is another thing to present an acceptable alternative explanation.

Most of the economists who have followed the debate do not seem to believe that monetarists have really provided a convincing alternative explanation to support their contention that a change in the money supply in and of itself can lead promptly and directly to a change in the demand for goods or assets. In the absence of wealth effects, there appears to be no way to explain how a change in money can have a direct effect on the income level.

Looked at in this way, it is now certain that the difference between Keynesians and Monetarists is not whether changes in the money supply affect the income level or not but in how they effect it and how close and how stable the relationship is between changes in the money supply and the income level. The Keynesian approach finds the relation to be a loose one or one subject to considerable variation over time; the Monetarists, on the other hand, maintain that the relation is fairly close or one subject to only moderate variation over time.

The Keynesians and Monetarists present very similar descriptions of the process of portfolio adjustment—but they disagree on a critical aspect of the process—the closeness of substitution between money and other financial assets and between money and real assets. To the Keynesians, it is money and other financial assets that are close substitutes. To Monetarists and Friedman, it is real assets and not financial assets that are close substitutes for money. He believes that the demand for money is not interest-elastic and what the people choose to do is to hold more real assets or goods and less money or to substitute real assets for money.

Thus, the crux of the difference between Keynesian and monetary theories seems to be found in this difference between them on the matter of substitutability amongst assets. Since such a relationship is the essence of monetarism, the issue of the closeness of the substitution between money and financial versus real assets is crucial.

If real assets are closer substitutes for money, than other financial assets, we are led toward the quantity theory; if financial assets through interest variations are closer substitutes for money, we are led toward the Keynesian theory or toward the rejection of the quantity theory. But the debate goes on. Here, we have hardly touched one aspect of what is actually a wide ranging debate between Keynesianism and Monetarism.

This aspect is a basic one because it touches the problem of the importance of changes in the money supply as a determinant of changes in the income level. The Monetarists insist and persist in their belief that money is the key determinant of such changes— Keynesians are equally emphatic and insist that money plays nothing like the decisive role ascribed to it by the monetarists. Thus, one of the great implications of Friedman’s or monetary approach is that because there is a stable relationship between the quantity of money and the level of national income in the long-run, the task of the monetary authority is to let the money supply rise in accordance with the growth rate of GNP.

In the short run, he argues that monetary authority should not tamper with the money supply in an effort to influence interest rates in order to produce changes in aggregate demand. This is in sharp contrast with and directly contradicts the Keynesian view that monetary policy should be directed toward finding the interest rate which will equate the level of investment with the level of full employment saving in the economy.

Conclusion:

Having examined the various theories of the quantity of money, one may say that from an historical viewpoint, the quantity theory of money has been a very important part of economic theory, because several important ideas have grown out of these theories and that they continue to influence the best minds in monetary economics. It is, therefore, not correct to say that the quantity theory is outworn or has outlived its utility.

One thing is clear, that the stricter versions of the theory can no longer be considered tenable or useful. Fisher’s equation is at the most a simple truism and its use has nothing to do with the quantity theory. Under the present circumstances, it is not possible to accept that a change in the quantity of money by certain percentage will change the price level in the same proportion, nor can we agree that velocity is a constant in the short-run. That the quantity theory has been able to survive at all is probably due to the fact that, in the Cambridge Cash Balance Version, the key variables concerned the choices made by economic units.

The Keynesian liquidity preference theory can still be defended, to some extent, on the ground that, if unemployment exists, changes in money supply may lead to more spending and expanded output rather than higher prices. But even,_ Keynes theory needs correction, on account of the acceptance of the ‘real balance effect’ by many- monetary economists. Some critics and commentators claim that it no longer makes sense to distinguish between the quantity theory and other theories of money.

They claim, there is, rather, the theory of money, which includes the elements of the quantity theory. (This overstates the degree of agreement reached so far). Although Friedman’s approach is fairly different from the cash balance approach, he has followed it in emphasizing choice and the marginal character of monetary decisions.

It is probably fair to say, that a minimum consensus has been reached—regarding the following:

(a) People’s decisions regarding their holding of money as well as other assets should be studied by the application of the general theory of choice—to use Johnson’s phrase. Such an approach facilitates the integration of monetary theory and the rest of the economic theory.

(b) The demand for money is dependent on several major variables. Each of these variables may be viewed as the rate of yield of a particular type of asset—the yield on bonds, on human and on non- human capital, the yield of money itself as a means of avoiding risk and adding to convenience.

(c) The money supply will help determine several variables, including the price level, but including also the level of output. However, the agreement, no matter how limited, does not indicate the discovery of truth.