Let us make an in-depth study of the sectoral change in India’s national income.

Colin Clark had pointed out in the 1930s that as the pace of economic development quickens, the importance of primary sector in terms of contribution to national income diminishes.

This sort of change in the sectoral distribution of national income has occurred in India during the plan period, thereby indicating economic development.

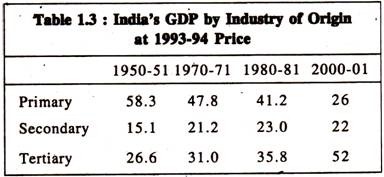

In 1950-51, the share of the primary sector in GDP was as high as 55.8%, while that of the secondary sector was only 15.2%. There has been a steady decline in the share of primary sector since then. It fell to 26% in 2000-01. On the other hand, over the entire plan period, as the industrial sector expanded, its contribution to GDP had been increasing and it rose to 22% in 2000-01.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Along with the growth of the secondary sector, the tertiary sector has also registered a higher growth during the last 50 years of planning. In 2000-01 its contribution was 52%. Table 1.3 indicates the sectoral distribution of GDP (at factor cost) during the period between 1950-51 and 2000-01.

Table 1.3 shows that, compared to the secondary sector, the share of the tertiary sector (comprising mainly the service sector) improved much, from 29% in 1950-51 to 52% in 2000-01. -The increase in contribution has been shared equally by the sub-sectors like transport, communication, trade, finance and real estate, community and personal services.

The changing structure of national income, therefore, indicates industrialisation, though at a slow pace. Furthermore, one also notices structural changes within the industrial sector. During the plan period, India’s industrial structure tilted heavily in favour of capital goods industries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This, of course, is a sign of industrialisation. But since then, industrial structure has become heavily biased in favour of consumer goods industries. It is the organised manufacturing and mining industries that have fared well as compared with unorganised small enterprises. Yet, unregistered small and tiny sectors occupy a dominant position in the Indian economy as necessary supports to these industries are given by the Government.

The tertiary sector is not a homogeneous category. It indicates trade, transport and communications, banking and insurance, real estate and dwellings, public administration, community and personal services. The combined share of these heterogeneous activities rose from 29% in 1950- 51 at 1993-94 prices to 52% in 2000-01. As a result of a better growth recorded in the tertiary sector one sees a significant change—a “change from a subsistence to a market-oriented economy”.

This is an indication of modernisation of the economy. Modernisation is marked by the increasing use of industrial inputs (like chemicals, machinery, electrical and transport equipment) for agricultural sector, particularly after the Green Revolution in agriculture in the late 1960s. Thus, it is clear that all the sectors in an economy do not grow uniformly; some grow at a higher rate than others.

Another aspect of India’s national income growth is the contribution of the public sector in GDR. The contribution of the public sector in GDP rose from 10.7% in 1960-61 to 20.8% in 1981-82 and to 28.6% in 1993-94. But it fell to 22.1% in 1999-00 mainly due to privatisation of several public sector units.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

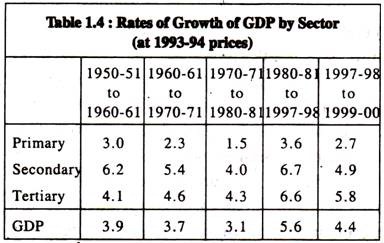

In India, a clear trend is also observable in recent years, viz., a slow growth of the commodity (i.e., primary and secondary sector) and a rapid growth of the services sector shown in Table 1.4.

The above table shows that the rate of growth of the non-commodity sector, i.e., the services sector, is much more faster than the commodity sector. This also reflects structural change of the Indian economy in respect of the distribution of GDP between the commodity sector and non-commodity sectors.

On the basis of these national income trends and structural changes, we can conclude that the Indian economy can no longer be described as a typical under-developed country. Definitely, some developments have taken place.

Nevertheless, black spots are there. Growth is still inadequate and much of its increase is eaten away by the growing mouths, despite some favourable structural changes. It is hoped that by the turn of the century sectoral composition of India’s national income will move further in favour of secondary and tertiary sectors.