The following points highlight the eight main factors influencing price elasticity of demand. The factors are: 1. The Availability of Close Substitutes 2. Definition of the Commodity 3. Importance in Consumer’s Budget 4. Necessities Vs. Luxuries 5. Time 6. The Number of Uses 7. The Prices of Related Goods 8. Economic and Human Constraints.

Factor # 1. The Availability of Close Substitutes:

In general if a commodity has a large number of close substitutes its demand will be elastic. If the price of the original commodity rises by a modest 2% the quantity demanded of the same may fall by more than 2%.

It is because consumers can quickly switch over to substitute products and thus cut back their consumption of the original commodity. Colgate toothpaste or Hamam soap each is supposed to have a relatively high price elasticity of demand because of the availability of a number of close substitutes.

On the other hand the demand for electricity is inelastic because it has no close substitute. Thus consumers are unlikely to be very much responsive to price. Thus the availability of close substitute implies a high price elasticity of demand.

Factor # 2. Definition of the Commodity:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The numerical value of the coefficient of price elasticity also depends on how narrowly or broadly a commodity is defined. Food is a very broad item of human consumption and the demand for food is inelastic because it has no close substitute.

But there are different varieties of food. For example, we can think of Chinese food, Indian food, vegetarian food, non-vegetarian food and so on. So within the food group itself we can think of various substitutes.

Thus, if the price of a particular variety of food increases the quantity demanded of other varieties will increase. This explains why the demand for synthetics is more elastic than the demand for clothing in general. So the more narrowly a commodity is defined the larger will be range of substitutes and higher the value of the elasticity coefficient.

Factor # 3. Importance in Consumer’s Budget:

The percentage of consumer’s income spent on a product also affects its price elasticity of demand. The larger the percentage of consumer’s income spent on a product the more elastic will be its demand. This explains why the demand for housing is more elastic than the demand for bread. A 5% increase in the price of bread will lead to a small cutback in its consumption compared to a 5% increase in the price of housing.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, the importance of any given item in the budget depends, at least partly, on the size of the budget itself. For example, as one’s income increase, the proportion of income spent on food gradually decreases.

Thus, if the price of food increases poor people will be forced to curtail their consumption of food more drastically than rich people who spend a very small percentage of their income on food. Thus, the price elasticity of demand for food is likely to be higher for poor people than for the rich.

Factor # 4. Necessities Vs. Luxuries:

In general it is believed that the demand for necessities is more inelastic than the demand for luxuries. It is because the demand for necessities cannot be postponed indefinitely or reduced drastically. So changes in their prices are unlikely to evoke much consumer response. But since we can go without luxuries at least for some time, the demand for such goods is elastic.

This is why the demand for textbooks is more inelastic than the demand for novels. However, it becomes very difficult at times to draw a distinction between the two classes of commodities. It is because what is a necessary good to one individual may be a luxury good to another individual.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For example, a car is a necessary good to a doctor but a luxury good to a service-holder doing a routine job. The above factors, though different, are closely interrelated.

For example, the demand for Sorbitrate, a very important drug for heart patients, is inelastic for three reasons:

(1) It has no close substitutes,

(2) It comprises a small part of the total budget of buyers, and

(3) It is regarded as highly necessary goods.

Factor # 5. Time:

Time also pays an important role in affecting the numerical value of the coefficient of price elasticity. People in general require some time to adjust their expenditures in response to a change in price. This explains why price elasticity of demand is smaller in the short run than in the long run.

Consider the impact of a rise in the price of petroleum after a budget. The immediate effect of this on car owners is likely to be negligible. People cannot quickly switch over to more fuel-efficient cars. But as time passes, people attempt to sell out old cars and replace those by smaller, high-mileage models (like Maruti cars).

Consider another example. Suppose the price of meat rises disproportionately to other food items. Eating habits established over years will be slow to change, but if the price remains high, people will begin to find out substitutes, this effect has recently been observed in U.K. where people have switched over to cheaper meat varieties such as hamburgers.

Thus following a change in price, elasticity of demand will tend to be greater in the long run than in the short run.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is also possible to think of an opposite situation. Suppose, for example, that train fares rise sharply after the presentation of the Railway Budget. People may initially respond to this by switching to buses, buying bicycles or walking. Thus they are initially very much responsive to price change.

However, after a few days they will discover that the buses are too slow and irregular, bicycles are not safe in busy roads and unpleasant in summer and rainy season and walking is too arduous. Therefore, after some time, people will switch back to trains. In this case elasticity will be less in the long run than in the short run because consumers find the substitutes unsuitable.

Factor # 6. The Number of Uses:

The greater the number of uses to which a commodity can be put, the greater its elasticity of demand. The reason is easy to find. If a product has many uses then there are different markets on which price changes can exert their influence. This enhances the possibilities of developing substitutes in some of the markets.

Consider, for example, electricity (or coal) which has many uses — heating lighting, cooking, etc. A rise in the price of electricity (or coal) might cause people to economize in their uses of electricity and also to substitute other fuels for some uses.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Factor # 7. The Prices of Related Goods:

The demand for a commodity depends not only on its own price but also on the prices of other goods. A rise in the price of a product (say coffee) is likely to cause the demand for its substitutes (say, tea or cocoa) to rise and the demand for its complements (say sugar or milk) to fall.

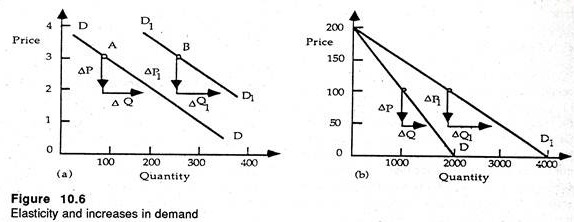

The effect of this upon elasticity is shown in the diagram below:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In both the diagrams there has been an increase in demand. Therefore, the demand curve has moved to the right. However, in Figure 10.6 (a) the shift of the whole curve to the right has reduced its elasticity.

But in diagram (b) where demand has increased by a constant percentage at every price, elasticity has remained unchanged. As John Bear- shaw put it: “An increase (or decrease) of demand by a constant percentage leaves elasticity unchanged, but a rightward shift of the curve by a specific amount reduces elasticity.”

Factor # 8. Economic and Human Constraints:

Thus we have seen that elasticity of demand is determined by many factors. A close scrutiny reveals that nearly all these factors depend upon the possibility of substitution.

However, the possibility of substitution is restricted by two main constraints. Firstly we can refer to human nature, with different tastes of different people and their different aspirations. So what is an acceptable substitute for one individual may be a poor substitute for another.

Secondly, we have to speak of the physical and economic constraints of the natural world. For instance, in the last two decades most people had to cope with sharp rise in the price of petroleum. Although there are substitutes it appears that it will take people many years or even decades to adjust to them adequately or to develop close substitutes.