A choice between alternative techniques of production is a major problem in the planning for developing countries. This is because a particular choice of technique of production affects not only the magnitude of employment but also the rate of economic growth. Several alternative techniques of production are available to produce a commodity and these differ with regard to the amount of capital being used with a unit of labour for production. In other words, the various techniques differ with regard to capital intensity which is generally measured by the magnitude of capital-labour ratio (K/L).

Thus, the higher the capital intensity, the more will be the quantity of capital as compared to labour will be used to produce a given level of output. On the other hand, the lower the capital intensity, more employment for labour will be created. Thus, the lower capital intensity implies the higher labour intensity. Therefore, in labour-surplus developing countries, it is generally believed that for rapid growth of employment labour-intensive techniques (i.e. less capital-intensive techniques) should be preferred.

Factor Price Ratio and Choice of Technique:

In economic theory based on the perfect competition model where the factor prices are given and constant for a firm and factor proportions are variable, the choice of a technique or capital- labour combination is easily made by a from which aims to minimize cost for a given level of out- put through equating relative prices of factors to their relative marginal products. In a developing country where labour is abundant and capital is scarce, price of labour (i.e., wages) should be low and price of capital (generally measured by rate of interest or user cost of capital) should be high.

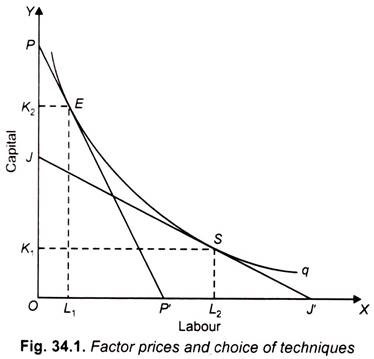

In Fig. 34.1 where an isoquant representing a given level of output has been drawn with amount of labour measured on the X-axis and amount of capital measured on the Y-axis. A factor price line, often called iso-cost line JJ’ has been drawn which in Fig. 34.1 represents the lower price (wages) of labour and higher price of capital which is in accordance with the factor endowments of a labour- surplus developing economy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The firm which aims to minimize cost for a given level of output (q in our Fig. 34.1) will choose a factor combination point S at which the iso-cost line JJ’ is tangent to the isoquant q and will use OL2 amount of labour and OK1 amount of capital and represents a labour-intensive technique.

However, it has been found that in developing countries due to factor-price distortions, which make labour relatively more expensive and capital relatively cheaper, the actual iso-cost line instead of being more flat as JJ’ is steeper as shown by PP’. With PP’ as the iso-cost line showing relatively more expensive labour and cheaper capital a firm on isoquant q will choose factor combination E which represents a capital-intensive technology and uses OL1 of labour and OK2 of capital. Thus in a labour-surplus economy, labour-intensive technique may not be actually chosen by a cost-minimizing firm because of the existence of distortions of factor prices from their true scarcity values.

Now, the question arises why in labour-surplus developing countries factor prices are distorted? The pressure of trade unions of labour for higher wages, minimum wage legislation fixing wage at higher level make labour costlier on the one hand and lower interest rates fixed either by the government if interest rates are administered by it or by cheap credit policy followed by the Central Bank make capital relatively cheaper. Further, liberal investment allowance (i.e., tax break) on capital investment also lowers the cost of capital and encourages the use of more capital. Besides, overvalued exchange rate makes the import of capital equipment cheaper.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Therefore, in order to ensure the use of labour-intensive or less capital-intensive techniques in order to maximise employment of labour it has been suggested that factor prices must be set right, that is, labour should be made cheaper and capital relatively more expensive.

In our above analysis, it has been assumed that there exists a high degree of elasticity of substitutions between factors and if factor prices are set right, labour-intensive technologies will be used.

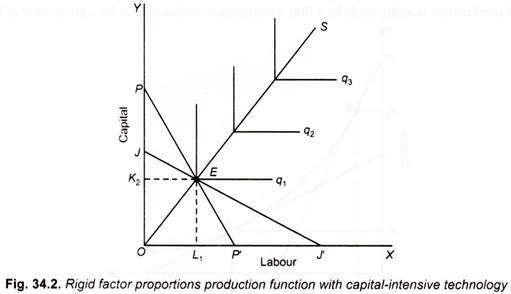

However, there has been a contrary view that production function of commodities is such that shows the existence of rigid factor proportions for the production of industrial goods in which the choices of techniques are few and of a relatively capital-intensive variety. The extreme case of rigid factor proportions production function is shown in Fig. 34.2 where for production of output q1 of a commodity, a larger quantity of capital Ok2 and relatively smaller quantity L1 is used. With a factor-price ratio line PP’, the equilibrium to produce q1 of the commodity is reached at point E which represents capital-intensive technique.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this case even if factor prices are set right and labour is made cheaper and capital costlier so that factor price line (i.e., iso-cost line) changes to JJ’, to produce output q1, of the commodity the same factor ratio, K2 of capital and L1 of labour will be used in equilibrium,. In such a fixed-proportion factor production function as the economy expands along the expansion path OS, the growth of labour employment will be very small.

We conclude that if production function is rigid or nearly rigid, then correction of factor price distortions will not ensure the choice of a labour-intensive technique of production and faster rate of growth of employment as the economy grows. However, the empirical findings do not support the existence of rigid factor proportions production function. It has been found that although the elasticity of substitution is not very high as shown by the isoquant q in Fig. 34.1, but it is around 0.5 which implies that if labour is made cheaper by reducing wage rate and capital is made costlier, labour will be substituted for capital and, as a result, a relatively more labour-intensive technique will be used. Thus correction of factor- price distortions will ensure higher rate of growth of employment of labour as the economy expands.

Choice of Techniques – Maximum Reinvestible Surplus Criterion:

The maximum reinvestible surplus criterion has been put forward by Galenson and Leibenstein. In their view the choice of technique in planning for developing countries is not to be decided from the point of view of private profit maximisation or private cost minimisation. In it choice of capital intensity has to be decided keeping in view the problem of mass unemployment and the need for rapid economic growth to raise levels of living of the people.

The problem is made difficult because the achievement of the twin objectives of reducing unemployment and promoting rapid economic growth through a choice of technique clash with each other at least in the short run. For the optimum choice of technique of production or capital intensity two alternative criteria have been compared by Galenson and Leibenstein. They are the maximum output and maximum reinvestible surplus criteria.

To explain these criteria let us take a single product model in which two factors, capital and labour, are used to produce a commodity. We further assume that there is a given amount of capital but the form it takes varies depending on the technique it embodies. With a given amount of capital, output of the commodity becomes a function of labour. We represent this production function and explain the two alternative criteria with the help of Amartya Sen’s diagram.

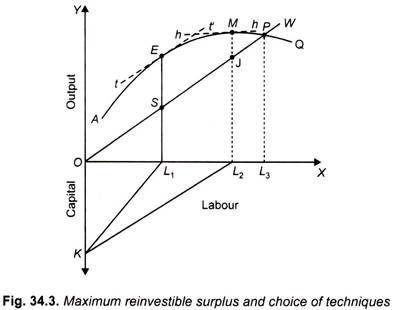

In this Fig. 34.3 along the X-axis, labour input is measured and along the y-axis (upward from the origin) output is measured and also on the Y-axis (downward from the origin) amount of capita is measured. OK is the given amount of capital available which takes different forms according to different degree of capital intensity. The line OW measures the wage bill, given a wage rate equal to the slope of the wage line OW. It should be noted that with the increase in labour employed, given the stock of capital OK, capital-labour ratio falls (or labour-capital ratio increases).

Thus, as we use more labour input, capital intensity will fall as we move rightward along the line OX. It should be further noted that, given the wage rate, as more labour is used total wage bill will be increasing. Thus with OL1 labour employed L1S is the wage bill and with OL2 labour employed L2J is the total wage bill. With capital stock equal to OK, output is a function of labour which is given by the production function curve AQ. In drawing this production function we have assumed that as more labour is used with a given capital stock there occurs diminishing returns to labour and ultimately with increasing labour intensity, total output declines, so that a certain labour-capital ratio corresponds to maximum output.

We are now in a position to explain the choice of technique on the basis of maximum output and maximum reinvestible surplus criteria. If the planner wants to choose capital intensity (i.e., technique of production) to maximise output, then he will choose point L2 where output is maximum (at OL2 marginal product of labour is equal to zero).

With the given capital stock OK, capital intensity chosen will be equal to the slope of the line L2K, i .e. OK/OL2. With the choice of capital intensity, (i.e., capital labour ratio, OK/OL2), OL2 labour is employed. If maximisation of employment in the present is desired, then, obviously, capital-intensity OK/OL2 is the optimum choice. However, maximisation of present employment may not yield a satisfactory rate of growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The surplus of output over total wage bill at OL2 level of employment is MJ which is not the largest. If the maximum of surplus over wage bill is required, then the capital intensity (or in other words, employment of labour with the given capital stock) at which the wage rate equals the marginal product of labour should be chosen. From Fig. 34.3 it will be noticed that at OL1 use of labour input or capital intensity represented by L1, the marginal product of labour (measured by the slope of the production function curve AQ at point E) equals the wage rate (as measured by the slope of the wage line OW).

The surplus of output over the wage bill at capital intensity at L1, (which is equal to OK/OL1) is ES which is the largest under the given circumstances. At L1, the capital intensity is higher but employment smaller than with capital intensity at L2. Thus, the largest surplus ES is obtained with a higher capital intensity and lower labour employment at the present.

If it is assumed, as is done by the exponents of maximum reinvestible surplus criterion, that the whole surplus is reinvested and the whole wages are consumed, then this larger surplus on being reinvested would yield a higher rate of economic growth. On the other hand, with lower capital intensity at L2, though the level of present employment is larger, surplus MJ is smaller which when reinvested would yield a lower rate of growth. With a higher capital intensity and higher rate of growth, the rate of growth of employment will be higher, though the level of present employment will be less. On the contrary, with a lower capital intensity, the surplus is smaller and concurrently rate of growth of output and employment will be smaller, though the present level of employment will be large.

Thus the choice of capital intensity implies the choice between the higher levels of present employment and output on the one hand and the higher rates of growth of employment and output on the other. Thus, it is argued if you are interested in maximising the current level of employment (and production) choose a lower capital-intensive technique such as the one represented by L2.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On the other hand, if you want a higher rate of growth of employment and output choose a higher capital-intensive technique such as the one represented by L1. Thus we find that there is a conflict between maximising present employment (or consumption) and maximising rate of growth of output and employment. Galenson and Leibenstein’s maximum reinvestible surplus criterion has been criticised for its assumption that all profits are saved and reinvested and all wages are consumed.

It has been pointed out that capitalists consume a lot of profits earned by them as they indulge in conspicuous consumption. Further, they point out that all wages may not be consumed and workers do save from their wages. In case of State enterprises it has been pointed out that due to their inefficiency, they may not generate much surplus and if they have some surplus they may be spent by the government for their current consumption expenditure.

Furthermore, in case of multinational corporate companies (MNCs), operating in developing countries they are likely to repatriate their profits (i.e., surplus) to their home countries rather than reinvesting them in the developing countries. A more important critique of maximum reinvestment criterion is that it is best to raise necessary savings or surplus through the use of appropriate fiscal and monetary measures rather than using choice of technique for the purpose.

Further, it is unrealistic on the part of Galenson and Leibenstein to assume that the wage rate is constant whatever technique of production is chosen. In this connection it may be noted that MNCs using capital intensive techniques in their production process are likely to pay higher wages to their workers which will reduce the reinvestible surplus and promote higher consumption on the part of their workers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Lastly, Galenson and Leibenstein ignore the role of other factors such as the availability of raw materials, skilled labour and foreign exchange to import capital goods required by the investment plan.

Conflict between Maximising Employment and Maximising Production:

When new projects for investment are planned, there is likely to be greater scope for varying the amount of labour employment. For example, a given amount of resources may be invested in either handlooms or automatic looms which employ quite different amounts of labour. It may, however, be noted that a given amount of new investment in labour-intensive and capital-intensive techniques may result in different levels of output; labour intensive techniques may yield less output as compared with capital-intensive techniques.

Thus, while the labour-intensive techniques are characterised by higher labour-output ratios, it is not necessary that all such techniques have lower capital-output ratio. For instance, it is worthwhile to note that Amartya Sen has shown that the labour-intensive technique of Ambar Charkha has higher capital-output ratios than the factory methods. Dhar and Lydall have also found that some labour-intensive small-scale industries have higher capital-output ratios. Hence, a conflict between output and employment arises. However, the decision whether output should be sacrificed or employment will depend upon the social welfare function.

Given the extent of unemployment and underemployment and the glaring disparities of income we feel that some output is worth sacrificing for more employment. Provision of employment is by far the most important way of raising the people above the poverty line and of ensuring widespread sharing in the fruits of economic development. In addition, employment gives an individual a sense of participation in socially gainful activity and prevents the feeling of being not wanted which has a great demoralising effect. Indeed, as has been remarked by Barbra Ward, “of all the evils worthlessness is the worst.”

It should however be noted that all labour-intensive techniques do not have higher capital- output ratio and therefore in their case conflict does not arise between maximizing employment and maximising production. In fact, in many labour-intensive techniques and small-scale industries, capital-output ratio is lower than the corresponding large-scale industries. Hence cases for encouraging such industries in developing countries like India.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Conflict between Maximising Current Employment and Maximising Rate of Growth of Production and Employment:

Conflict which generally arises relates to the maximisation of current employment and maximisation of rate of growth of production and employment. As seen above, from Sen’s analysis of choice of techniques, maximisation of output-employment in the current period will not lead to the higher rate of economic growth of both output and employment. This question is of particular importance in respect of- (a) allocation of resources for investment between capital goods and consumer goods and (b) the choice between labour-intensive and capital-intensive techniques.

Maximising rate of growth of production now at the cost of present employment makes it possible to use extra output produced for generating more employment in the future. It is worth noting that more output (i.e., more reinvestible surplus) is useful not only for its own sake but enables the planners to generate more employment opportunities in the future. Thus, a conflict (and therefore inter-temporal trade-off) arises between more employment now and more employment tomorrow.

Let us explain how conflict arises in the two cases explained above. Allocation of more resources to the production of investment goods by sacrificing some employment in the present (that is, if extra output is in the form of capital goods such as machines etc.) will enable us to provide employment to more men in the future. Similarly, if extra production is in the form of more wage goods – liquid capital as they are sometimes called – it enables the planners to create more jobs in the future as the availability of wage goods limits the opportunities for creation of employment opportunities.

On the contrary, raising employment now means sacrificing not only some production in the current period but also lowering the rate of growth of employment. Thus with the allocation of resources to the consumer goods industries ensuring more employment now, level of employment at some future date would be lower than would have been possible if more allocation of resources to capital goods industries in the present was preferred.

Turning to the conflict between current employment and the rate growth of employment arising out of the choice of techniques of production, Galenson and Leibenstein, Sen and others have shown that the choice of labour-intensive techniques, though maximises employment in the current period, will reduce the share of profits (or invertible surplus) as compared to wages. And the reduction in profits will adversely affect the rate of saving and investment and therefore the growth of output and employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On the contrary, if capital-intensive techniques are chosen, they may yield less employment (and output) in the present but they will yield more surplus or profits as compared to wages. Therefore, the choice of capital-intensive techniques will ensure higher rate of growth and therefore more employment in the future. Here, the conflict or trade-off involved does not arise between current output and current employment. Instead, there is intertemporal trade-off, that is, more employment now or more employment tomorrow. It means that some more unemployment in the present may be tolerated for the sake of generating more invertible surpluses (profits) so that higher growth rate is achieved and more employment opportunities are provided in the future.

But the above argument regarding capital-intensive techniques yielding more employment in the future is based on the crucial assumption that a major part of profits is reinvested and most of wages are consumed. Besides, account should also be taken of the fact that increase in consumption of the poor and unemployed will generate demand for basic wage goods which are produced with much more labour-intensive techniques as compared to those used in the production of goods demanded by the rich. Thus only a part of any increased income going to the rich will be saved and the part that will be spent would generate less employment than a similar amount of spending by the poor. In view of these, the use of capital-intensive techniques will not necessarily promote more rapid growth of employment and output.

Appropriate or Intermediate Technology:

As has been stated above, the growth of organised or large-scale industries with modern capital- intensive technology yields only meagre employment opportunities. Therefore, in order to create adequate employment opportunities through industrial growth, there is a need for developing and adopting an ‘intermediate technology’ which requires less capital per work place without loss of efficiency.

Besides, to prevent excessive urbanisation and concentration and to arrest the tendency for mass migration into the urban areas, there is need for adopting a strategy for rural industrialisation, based on small-scale manufacturing using intermediate technology dispersed throughout the countryside to increase rural employment and income. Dr. E.F. Schumacher, the advocate of the adoption of intermediate technology, rightly says, It is surely an astonishing error to assume that the technology developed in the West is necessarily appropriate to the developing countries.

Granted that their technological backwardness is an important reason for their poverty- granted too, that their traditional methods of production, in their present condition of decay, lack essential viability- it by no means follows that the technology of the richest countries is necessarily suitable for the advancement of the poor.

It must never be forgotten that modern technology is the product of the countries which are ‘long’ in capital and ‘short’ in labour, and that its main purpose, abundantly demonstrated by the trend towards automation, is to substitute machines for men. How could this technology fit in the conditions of countries which suffer from a surplus of labour and a shortage of machines? He further remarks that “technology devised primarily for the purpose of saving labour should be inappropriate in a country troubled with a vast labour surplus could hardly be called surprising”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is worth noting here that research in India, after making proper cost and price calculations, has already discovered intermediate technologies for producing some thirty types of such goods as agricultural implements, processed foods and consumer goods which are actually cheaper and more efficient than those produced by the advanced machinery.

It should be further noted that the evolving of intermediate technologies for various industries does not imply discovery of altogether new principles of science and engineering. What is required is the application of the basic principles of modern science and engineering to evolve the production techniques which conform to the factor endowments of the labour-surplus economies.

These appropriate or intermediate technologies may be obtained by scaling down advanced techniques by adapting them so as to make them more labour intensive, or by scaling up handicrafts techniques with the introduction of new tools and simple machines and thus improving economic efficiency of these techniques while maintaining their labour-intensity. In this process of adaptation product design itself will also have to be modified and standardised. Further, entirely new appropriate technologies have also to be evolved from the applications of the basic principles of modern science and engineering so as to suit the labour-surplus conditions of developing countries. For that, a good deal of research and development is required to be undertaken.

It may be noted again that Japan’s remarkable adaptability has been reflected not only in agricultural techniques but also in the extent to which it has organised its new industries efficiently on a cottage industry basis. Here, as in agriculture, Japan’s production methods are especially well-suited to the conditions of labour-abundant economies. Lastly, it may be noted that recently, four East Asian countries, namely, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong-Kong and Singapore, which have achieved remarkably higher growth rates and are therefore called Asian Tigers followed labour-intensive path of economic growth. That is, they used relatively much more labour in their industrial development than India.