Let us make an in-depth study of the Classical Theory of the Interest Rate.

In the classical system all the three concepts of aggregate domestic expenditure — consumption, investment and government expenditure — play an explicit role in determining the equilibrium interest rate.

In truth, the interest rate ensures that exogenous changes in any component of aggregate demand do not affect the level of aggregate demand for commodities.

In the classical theory the equilibrium rate of interest was the one which equals the supply of loanable funds (originating from the household sector) to the demand for loanable funds (originating from what businesses and governments desired to borrow). Borrowing consists of selling a standard bond which promises to pay certain amount in the future or a perpetuity that pays a fixed interest forever such as an annuity (which does not have any maturity date).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Lending consists of buying such bonds. The rate of interest is, from one side, the return to holding bonds and, from another side, the cost of borrowing. It, therefore, depends on two sets of factors — (a) factors that determine the level of bond supply (borrowing) and (b) bond demand (lending).

In the classical system bonds are supplied by both firms and governments. Firms sell bonds to finance all investment expenditures. The government might sell bonds to finance spending in excess of tax resources.

In the classical model, business investment was a function of the expected profitability of investment projects and the rate of interest. Expected project profitability was assumed to vary with expectations of project demand over their entire economic lives.

And these expectations were subject to exogenous shifts in the expected profitability of investment projects. The portion of government deficit which was financed by selling bonds to the public was also an exogenous policy variable.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If expected profitability remained unchanged, investment expenditures varied inversely with the rate of interest. And business supply of bonds equaled the level of investment expenditure.

In the classical model, saving was positively related to the rate of interest because at higher rates of interest people saved more. The classical assumption was that in normal times saving was equivalent to a demand for bonds.

i. Equilibrium Rate of Interest:

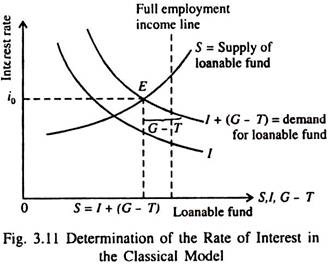

Fig. 3.11 shows how the rate of interest is determined in the classical model. The equilibrium rate of interest is the rate that equates the supply of loanable funds, which consists of new saving (5), with the demand for loanable funds, which consists of investment (I) plus the bond-financed deficit of the government (G – T), i.e., the portion of the deficit the government must choose to finance by selling bonds to the public.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. Stabilising Role of the Interest Rate:

The rate of interest acts as a stabiliser in the classical model. If, for instance, due to an exogenous event (e.g., apprehension of a war or revolution in near future) business people lower their expectations about future profits from investment, they will reduce their investment levels which would lead to a fall in the demand for loanable funds.

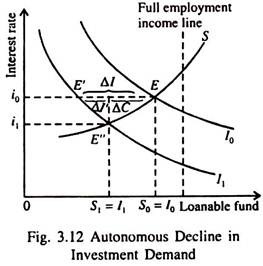

If we think of a situation where the government budget is balanced (G = T), private investment will be the only source of demand for loanable funds. Now if due to a fall in expected profitability of investment projects the investment demand schedule shifts to the left from I0 to I1, investment will fall by Δ I at the same rate of interest.

So there will be an excess supply of loanable funds at the original rate of interest which will cause the rate of interest to fall from i0 to i1.

As a result two types of adjustment will occur:

(i) Firstly saving will fall and consumption will increase, because full employment supply of output remains fixed (as shown by the vertical line in Fig. 3.11 and Fig. 3.12).

(ii) Secondly, investment increases by Δ I’ due to a fall in the rate of interest. New equilibrium occurs at the interest rate-with saving (the supply of loanable funds) again equal to investment (the demand for loanable funds).

At new equilibrium point E” the increase in consumption (fall in saving) plus the increase in investment caused by the drop in the interest rate — the distance Δ I’ + A C (= – Δ 5) in Fig. 3.12 — is just equal to the original autonomous decline in investment demand, Δ I. Since the interest rate falls, the sum of private sector demands (C + I) remains unchanged even if there is an autonomous decline in investment demand.

iii. Two Lines of Defence for Full Employment:

In the classical model there are two lines of defense for full employment — (1) the adjustment of the interest rate and (2) the self-adjusting properties of the classical labour market, which gets reflected in the nature of the AS curve. The interest rate acts as the stabiliser in the classical world.

Shocks that affect consumption demand, investment demand or government demand will not affect the demand for output and, therefore, will not shift the aggregate demand curve, i.e., will have no effect on output and employment simply because full employment output is predetermined in the real wage labour market.

So full employment is maintained, even in the presence of such shocks, by interest rate adjustments. The reason for this is the self-adjusting properties of the classical labour market which ensures that the aggregate supply curve is vertical. This is another factor leading to automatic full employment.