The below mentioned article provides a close view on the Say’s Law of Market.

Introduction to Say’s Law of Markets:

The most fundamental and central proposition of classical economics was Say’s Law of Markets, after J.B. Say, a French Economist (1797-1832), who first stated the law in a systematic form.

Briefly stated, this law means that ‘supply always creates its own demand.

In other words, according to J.B. Say, there cannot be general overproduction or general unemployment on account of the excess of supply over demand because whatever is supplied or produced is automatically exchanged for money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In an exchange economy whatever is produced represents the demand for another product because whatever is produced is meant to be sold. Whenever additional production takes place in the economy, necessary purchasing power is also generated at the same time to absorb the additional supply; hence, there is no scope of supply exceeding demand and causing unemployment. This law was the basis of their assumption of full employment in the economy.

The proposition rested on the plea that income is spent automatically at a rate which will always keep the resources fully employed. Savings according to classical are just another form of spending; all income, they believed, is in a large part spent on consumption and the rest on investment. There is no ground to fear a diminution in the flow of income stream in the economy. Hence, there cannot be any general over-production or unemployment.

In his analysis of the market mechanism, J.B. Say noted down; “A product is no sooner created, than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its value. When the producer has put the finishing hand to his product, he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest the value should vanish in his hands. Nor is he less anxious to dispose of the money he may get for it; for the value of money is also perishable. But the only way of getting rid of money is the purchase of some product or other. Thus, the mere circumstance of the creation of one product immediately opens a vent for other products.”

J.B. Say’s thinking became quite popular with the English economists. As the elementary principle of an exchange economy based on simple organisation of industry, it was quite an acceptable idea. As it was handed down, it came to be briefly stated as that “supply creates its own demand.” It meant that there cannot be any general over-production or general unemployment in the economy as whatever is produced is automatically consumed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It implied that every producer who brings goods to the market does so only to exchange them for other goods. Say believed that people did not work for its own sake but to obtain other goods and services that would satisfy their wants. To be employed simply meant to work in a field or to start a shop and to sell one’s own product in the market. The organisation of the economy was simple under which people spent on tools and consumer goods. Saving and investment were not separate processes.

The producer sold his product and not his labour. Products were exchanged for products. Realising the obviousness of the observation, Ricardo expressed Say’s Law of Markets in the following words: “No man produces but with a view to consume or sell, and he never sells but with an intention to purchase some other commodity which may be useful to him or which contributes to future production. By producing, then, he necessarily becomes either the consumer of this own goods or the purchaser and consumer of the goods of some other persons. Productions are always bought by productions; money is only the medium by which the exchange is effected.”

Say’s Law continued to underlie most of the developments in economic theory from David Ricardo to Alfred Marshall. None questioned its validity except Malthus who tried to give a theory of gluts but could not give an alternative theory to Say’s Law.

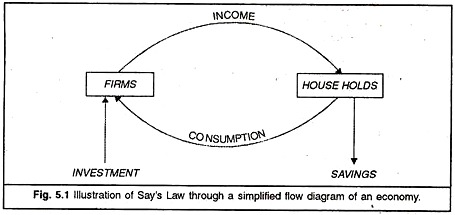

The neoclassical like Marshall and Pigou understood it in its latest form. Their belief was that during the process of production necessary purchasing power is generated which absorbs the additional supply. They understood Say’s Law as the process of equilibrium in a simple exchange economy as is shown in Figure 5.1. Households supply factor services to firms and earn income there from. The households either spend their incomes on consumption or save some of it. Firms get their sale proceeds from the sale of goods to households and also obtain funds from the household saving for investment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This maintains the circular flow of the economy; for example, when a new car is manufactured, necessary purchasing power is simultaneously generated in the form of wages, profits, etc. so that the car is used. Hence, there is no possibility of the aggregate demand becoming deficient. “Say’s Law, in a very broad way, is description of a free exchange economy. So conceived, it illuminates the truth that the main source of demand is the flow of factor incomes generated from the process of production itself… A new productive process, by paying out income to its employed factors, generates demand at the same time that it adds to supply.” They, no doubt, admitted that supply of a particular commodity may exceed its demand temporarily on account of the wrong calculations of businessmen, but general over production and hence general unemployment is impossible.

They admitted that specific commodities might be overproduced but a general glut in the sense of a general depression was unthinkable, for the very process of production creates the required effective demand necessary to absorb total output. If, however, due to some mistake, over-production comes to exist in respect of a particular industry, it will be corrected automatically when businessmen suffer losses and switch over from the production of goods they cannot sell to the production of goods they can sell.

Professor Mark Blaug has summed up Say’s Law thus: “In an economy with a developed division of labour the means normally available to anyone for acquiring goods and services is the power to produce equivalent goods and services. Production increases not only the supply of goods but, by virtue of the requisite cost payments to the factors of production, also creates the demand to purchase these goods. “Products are paid for by products” in domestic as much as in foreign trade, this is the gist of Say’s Law of markets.”

Assumptions:

The orthodox statement of Say’s Law as enunciated above is based, more or less, on the following assumptions:

(i) That the free enterprise system based on price mechanism provides a place for growing population and an increase in capital automatically.

(ii) In an expanding economy new firms and workers find their way into the productive process, not by displacing others but by offering their own products in exchange.

(iii) The extent of the market is not limited and incapable of expansion. The extent of the market is as big as the volume of products offered in exchange.

(iv) There is no necessity on the part of government to intervene in business matters so that the attainment of automatic adjustment is facilitated.

(v) Flexibility of interest rates and the long period were considered essential for its successful working.

Support of Say’s Law by ‘Classics’:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

J.S. Mill had supported Say’s Law and regarded it as extremely important. The older formulation of Say’s Law by Ricardo and James Mill was cast in terms of a society that has become mostly a matter of the past—a society in which producers were self-employed either as peasant proprietors, craftsmen, or as individual proprietors. Mill took note of the depressed state of the market accompanying a crisis.

At such times “… every-one dislikes to part with ready money, and many are anxious to procure it at any sacrifice.” Depression, Mill said, is “a glut of commodities or a dearth of money…. It is a temporary derangement of markets caused by contraction of credit.” Such periodic depressions, Mill felt, do not go to contradict Say’s Law.

Such maladjustments or disturbances do not prove that there are no powerful hidden forces tending to restore full employment equilibrium. Marshall, in his Principles (1890), strongly supported Mill’s views. Lack of confidence, Marshall felt was the chief cause of depression. When confidence is shaken “though men have the power to purchase, they may not choose to use it.” American orthodox economist, F.M. Taylor in his Principles (1921) endorsed Say’s law.

Business depressions, in his opinion, do not disprove Say’s law. He expressed the view that in the short run the smooth and automatic process of exchange of products may be broken by temporary disturbances but these do not invalidate the efficacy of fundamental forces (which Say’s Law sought to illuminate) tending automatically towards full employment.

Pigovian Formulation of Say’s Law:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Say’s Law of Markets, as enunciated above, was put by Pigou in a different form, a proposition denying the possibility of large scale involuntary unemployment for a long period of time. According to Prof. Pigou, there cannot be any general unemployment in the labour market if the labour is just prepared to accept a wage according to its marginal productivity.

In a free enterprise economy where there is free, perfect and thorough going competition, if the labourers just accept low enough wages, unemployment would vanish completely (except seasonal and frictional unemployment). Such conditions did prevail, according to Prof. Pigou, before the First World War and as a result there did not exist unemployment except in a temporary form.

After the War, however, circumstances had changed and certain new forces had arisen to weaken the competitive forces in the labour market. For example, minimum wage laws, collective bargaining, growth of trade unions, unemployment insurance, arrangements between workers and employers, group pressures and government intervention. These factors had gone a long way to make the labour markets imperfect and hence the chances of unemployment had multiplied. Therefore, reduction in wage rates could not take place.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Professor Pigou gave a new defence of the Say’s Law of Markets with his argument of increasing employment through wage flexibility. He suggested that when there is economy-wide unemployment and real wages are allowed to be cut via labour-market competition that reduces costs of production and prices. When the general price level goes down, the value of the wealth held by the general public increases which encourages greater consumption on the part of the wealth holders.

This argument of Pigou is popularly called the Pigou Effect. This increases the effective demand in the economy to the level where there is full employment. Thus, in Pigou’s view, if there is wage and price flexibility, then aggregate demand and aggregate supply get equated only at the level of full employment.

This conclusion, of course, implies the application of the quantity theory of money. The condition which the economy satisfies at full employment is Aggregate demand SP1D1 = SP1S1 = Aggregate Supply. This means that total expenditure is equal to total supply of output at the full employment level. In other words, that circular flow of income (Y) and expenditure (C +1) is maintained.

Implications of Say’s Law:

1. According to Say’s Law of markets there is automatic adjustment in the economy as whatever is produced is consumed. In other words, every output brings along with it the necessary purchasing power in circulation which will lead to its sale so that there is no overproduction. Hence, there is no necessity on the part of the government to intervene in business matters as that will come in conflict with the automatic adjustment mechanism of Say’s Law of Markets.

2. Since supply creates its own demand, hence general unemployment and over-production are impossible in a free enterprise, competitive economy.

3. Another implication of Say’s Law of Markets is that as long as there are unemployed resources in the economy it is profitable to employ them because they can have their own way. In other words, when the unemployed resources are used, they lead to more production so as to cover their own costs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. Another important implication is the mechanism of flexibility of the rate of interest which brings about equality between saving and investment. To classical, saving is another form of spending. Therefore, whatever is saved is necessarily invested. Hence, there is no possibility of the deficiency of aggregate demand and the mechanism through which it is maintained is the rate of interest.

5. Another implication of Say’s Law of Markets flows from the Pigovian formulation, i.e., wage rate is the mechanism which helps bring automatic adjustment, i.e., a lowering of the wage rate will lead to full employment under free and perfect competition. It led to the policy implication that the government should as far as possible, ensure a free market and there should be absolutely no regulation of wage rates, interest rates or prices.

6. Because goods are exchanged for goods, money acts as a veil and has no independent active role to play. Money is only a medium of exchange to facilitate transactions.

Critical Analysis of Say’s Law of Market:

As the depression of 1929 deepened and several years passed without signs of recovery, Say’s Law was called into question. Industries found it hard to sell all the output produced and there certainly seemed to be a general ‘glut’ in the economy.

In 1936, J.M. Keynes, a genius in several fields with an established reputation in monetary theory, worked a virtual revolution and rejected Say’s Law without qualification on the ground that aggregate demand need not be equal to aggregate supply at full employment.

Dissatisfaction with orthodox theory sprang from the fact that its conclusions failed to conform with the actual facts of the real worked. Economists had already begun doubting the universal validity of Say’s Law long before the advent of depression. Hobson criticised it much earlier, though in vain, as his tools were not so sharp as to inflict an injury on the prevailing orthodoxy, Aftalion in France, J.M. Clark in U.S.A. and D.H. Robertson in U.K. assailed it.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to Paul M. Sweezy “Historians fifty years from now may record that Keynes’ greatest achievement was the liberation of Anglo-American economics from tyrannical (Say’s Law)….”

The main points of criticism of Say’s Law of Markets were as follows:

1. Possibility of Deficiency of Effective Demand

2. Prolonged Depressions a reality

3. Fallacy of Aggregation

4. Misplaced Confidence in the Efficacy of Wage Cuts

ADVERTISEMENTS:

5. Wrong Assumption of Interest-elasticity of Investment

6. Presence of Monopoly Element in Product and Factor Markets

7. Importance of Short-run Economics

1. Possibility of Deficiency of Effective Demand:

It was assumed in Say’s Law that whatever is earned is spent either on consumption goods or on investment goods, thus, income being automatically spent at a rate which keeps all the resources employed. All this, however, was not supported by actual facts, as the income is not automatically spent on consumption and investment. Keynes pointed out that there could be a deficiency in aggregate demand as all income earned in producing an output would not necessarily be used to purchase it.

Keynes argued that money is an important form of storing wealth. That part of the current income, which is not spent, is saved and may go to increase individual’s holdings. Therefore, whatever is saved out of current income does not constitute investment because the opportunities for investment arc not unlimited.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We cannot say definitely that whatever is saved is spent on investment goods, rather it may go to swell the liquid assets of individuals. In this way, there can be a shortage of aggregate demand and the claim of Say’s Law that aggregate demand cannot be deficient at full employment is entirely defeated.

The fallacy of Say’s Law was revealed by Keynes’ division of aggregate demand into investment and consumption for purposes of income analysis (Y = C + I). Keynes pointed out that the factors which determine consumption are quite different from the factors determining investment but together these constitute the aggregate demand and determine the level of income.

Consumption is a function of current income, but it does not increase as much as the increase in income. Investment, on the other hand, depends upon technological development and the marginal efficiency of capital. It is, therefore, clear that the determinants of consumption and the determinants of investment are not inter-connected in such a way as to ensure adequate aggregate demand.

Hence, total demand would not always be such as would guarantee adequate market for the output. The stability of aggregate demand would be attained only when the gap between current income and current consumption is made up completely by the forthcoming amount of investment. Keynes, thus, found in the failure to spend the whole of current income on consumption and investment goods the cause of unemployment.

2. Prolonged Depressions a Reality:

Economic histories of capitalist economics bore testimony to the fact that it was not uncommon to experience a ‘glut’ in the economy such as between 1929-32. If supply creates its own demand there was absolutely no reason of stocks piling up in factories and a general slump setting in.

It was during this depression that employers faced with lack of adequate effective demand turned out large number of workers and put up ‘no vacancy’ signboards being afraid of a further fall in prices. Say’s Law stood practically discredited. This gave a rude shock to Keynes’ faith in Say’s Law and led to the discovery of his ‘General Theory’ of income and employment.

3. Fallacy of Aggregation:

Keynes pointed out that the main fallacy in Say’s Law was the belief that the principles which apply to an individual firm or industry could also apply to the economy as a whole. Keynes stressed that it was too much for Say’s Law to assume that microeconomic analysis could profitably be applied in macroeconomic analysis.

4. Misplaced Confidence in the Efficacy of Wage Cuts:

Pigou’s formulation of Say’s Law also came under heavy fire. Keynes pointed out that a general fall in wages is not likely to increase employment in the economy as a whole because wages are not only cost to the employers but also income to a large section of the population. With the purchasing power reduced, their demand of goods and services will also fall. According to Keynes, employment in the economy depends on aggregate spending (effective demand) and not on the real wage level.

5. Wrong Assumption of Interest-elasticity of Investment:

The assumption of interest-elasticity of saving and investment has also been challenged by Keynes. Say’s Law presumes that all savings are automatically invested and the rate of interest brings about the necessary adjustment Keynes, however, denied it on the ground that income and not the rate of interest is the equilibrating mechanism between savings and investment. Savings and investment are equated by changes in income and are not sensitive to the changes in the rate of interest.

6. Presence of Monopoly Element in Product and Factor Markets:

Besides there is a conventional objection to Say’s Law: that it presumed free and perfect competition in the economy. In practice, we can see that imperfect competition in the market is the rule and perfect competition only an exception because in modern capitalist economics there is a strong tendency towards monopoly. Imperfections in the factor and product markets are not temporary. They have come to stay. These hinder the working of the forces behind Say’s Law.

7. Importance of Short-run Economics:

Say’s Law has been defended at times, in terms of long-run equilibrium on the ground that the long-run aggregate demand tends to be sufficient to purchase all that the economy is supplying. This long run equilibrium is brought about by the free forces of market alone. But Keynes remarked “that in the long-run we are all dead.” People had waited for three or four years to see that the automatic corrective mechanism implied in Say’s Law would work, but in vain. It was not clear as to what is the length of the long-run in Say’s Law.

Relevance of Say’s Law in Barter and Money Economies:

According to the proponents of Say’s law, it holds true both under barter economy as well as under money economy. The law states that income received is always spent on consumption and investment. In other words, money is never hoarded. The money or expenditure stream (MV) remains neutral.

In a barter economy, every seller is essentially a buyer also. If the sellers sell their produce for money, the money will promptly be spent against other goods. Money is merely a convenient medium of exchange avoiding the leakages of barter and nothing more. Thus, the ‘law’ though framed in terms of a barter economy held true for an economy using money also. Money economy behaved in the same way as barter economy because rational individuals will not hold idle money. In this sense, there is indeed an identity of selling and buying under barter economy and even under money economy.

In his excessive zeal for establishing the practical importance of his thesis, Say expressed himself time and again, as if indeed, the total monetary value of all commodities supplied would have to equal to monetary value of all commodities demanded not only in equilibrium but ‘always and necessarily’. This is logically not supported if he actually meant it. The ‘law’ in that case becomes an identity, a simple truism. It is no more a theory explaining anything.

Not to speak of money economy, even in a barter economy the law has been found to be of extremely limited validity. To make it relevant even in barter economy, it will be necessary to prove that every one’s offer of goods and services at all exchange ratios is equal to what other people wish to take at the same ratios.

This is obvious nonsense, for disequilibrium is as much possible in a barter economy as it is in a money economy though the latter may display additional sources of disturbance. The older classicists viewed Say’s law in non-monetary terms and considered the exchange of goods against goods quite natural. The later classical, dealing with a money economy, recognised the monetary “slip between the cup and the lip” hoarding and debt cancellation.

In other words, Say neglected the store-of-value function of money and therefore the fact that there is demand for money for accumulating wealth is not accounted for in his theory. Much confusion would have been avoided if the store-of- value function of money or the demand for ‘cash to hold’ could be inserted into the theoretical system that Say had adopted, avoiding at the same time the necessity of refuting it or amending it.

Is Say’s Law Still Valid in Economics?

From the points of criticism enumerated above, it is beyond doubt that whatever force Say’s Law had during barter economy, it certainly does not hold true in modern conditions. Some economists have proved the basic classical proposition without any use of Say’s Law. They hold it superfluous even for classical policy conclusions. It has been completely abandoned by modern economists in their theoretical and practical work on money and business cycles.

Under barter economy where production was primarily for consumption, i.e., whatever was produced was exchanged for goods and services, Say’s Law had some meaning. But today, when production is based on future expectations and anticipations of demand, it has no such validity; there is bound to be some overproduction.

Viewed however as a broad generalization in micro context. Say’s Law presents in a greater measure a picture of the exchange economy wherein new firms and workers find their way into the productive process by offering their own products in exchange.

It was J. A. Schumpeter’s view that Say never presented the law in the form in which we find it to-day. Over the long period of time it has been used by a generation of economists, it was unjustifiably shortened to give a sweeping statement of the working of a free exchange economy. What he actually meant was that a good deal of production is always meant to be consumed and the rest, if saved, is likely to be invested generally.

Even to-day, therefore, the law is true to the extent production creates its own demand via payment to the factors of production and their resulting consumption expenditures on the goods produced. The very fact that there can’t be any stable equilibrium in the economy unless = C + I shows the general validity of Say’s law even under modern conditions and manifests its inherent strength of logic.

In other words, the sum of expenditures on consumption and investment demand must be high enough as to be equal to generated income (supply). Hence, in a sense Y = C + I is nothing but an elaboration of Say’s law in the short run. In their fondness for the law, people gave misleading and conflicting interpretations.

In this connection, J. A. Schumpeter remarks: “Most people misunderstood it, some of them liking, others disliking what it was they made of it. And a discussion that reflects little credit on all parties concerned dragged on to this day when people, armed with superior technique, still keep chewing the same old cud each of them opposing his own misunderstanding of the law to the misunderstanding of the other follow, all of them contributing to make a bogey of it.”

In the same vein, Prof. Hansen remarks: “History of thought illustrates again and again how a great living principle, tossed about on the sea of controversy is likely to lose its vitality. Too often it may be applied as a tool of analysis to highly complex problems for which it is unsuited. Misleading conclusions inevitable emerge. This is what happened to Say’s Law.” Say’s identity is now dead and buried. Long live Say’s Law!