Let us make an in-depth study of the nature and determinants of supply.

Nature of Supply:

Our object is to find out and study the factors which influence the quantities of a good that suppliers wish to produce and offer for sale.

However, a study of the theory of supply requires a background knowledge of certain pertinent facts. For example, we must know at the outset who the suppliers are, what are their objectives, what do they sell, and so on.

Suppliers:

In general, we use the term ‘suppliers’ to refer to organisations that make decisions about how many goods to supply at various prices and in different market situations. We use various other terms to refer to suppliers such as sellers, producers, businesses and enterprises. In short, the organisations responsible for supply of goods are called suppliers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

We assume that supply decisions are made by a single individual—the supplier. He (she) is treated as the basic unit of behaviour on the supply side of markets, just as the consumer is taken as the basic unit of behaviour on the demand side.

Sellers’ Objectives:

We initially assume that the objective or goal of a supplier is to make as much profit as possible. When a supplier succeeds in achieving this goal, he is said to have reached the optimal point. We do find similarity between the consumer’s goal of utility maximisation and the supplier’s goal of profit maximisation. In this context, it is interesting to note that profits can be measured in terms of money, but utility (or consumer satisfaction) cannot be directly observed or measured.

Time:

As in the theory of demand, the focus is on the quantity of a commodity offered for sale per period of time. This quantity is a flow such as Maruti cars per month or chocolates per week, etc. Thus, in all diagrams, we measure quantity per period of time (on the horizontal axis).

Price-takers:

We consider situations in which the number of sellers is so large that none of them can alter the market price by selling a little more or a little less.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Each supplier or trader is so small that he can exert little, if any, influence on price. So he takes the price as given and makes the decision regarding how much to offer for sale at a particular price per unit of time. This is known as price-taking behaviour. The suppliers are assumed to be price-takers.

In real life, however, we find few producers of certain commodities like motor cars or refrigerators or soaps. They can affect the market prices to some extent through their own behaviour.

Determinants of the Quantity Supplied of a Commodity the Supply Function:

There are five major determinants of the quantity supplied of a commodity in a particular market:

1. The price of the commodity

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. The prices of other commodities

3. The prices of factors of production

4. The objectives of producers, and

5. The state of technology (or the art of production).

This list of factors can be summarised in a supply function:

qx = S (Px, Py, Pz, f1, f2………………………..fn, O, T, etc.)

where qx is the quantity supplied of commodity x, px is its own price, py and pz are the prices of other commodities, f1, f2……fm are the prices of the factors of production, O is the objective of the firm and T is the state of technology. In fact, the goals of producers and the state of technology determine the form of the function S. Here qx is the dependent variable and all other variables on the right-hand side are independent variables. Thus qx is the function of all the variables shown on the right hand side. It means that qx depends on all the factors listed on the right side of the above equation.

Thus the quantity supplied of a commodity depends on a number of factors. The following factors bear relevance in this context.

Price of the Commodity:

The most important factor influencing the quantity supplied of a commodity is the price of the commodity under consideration. To start with, we assume that price is the only factor determining supply. We ignore the other influencing variables. So we make the ceteris paribus assumption here also. We assume all other variables influencing the supply decisions of producers remain un-changed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The basic hypothesis in the theory of supply is that the quantity of a commodity a producer will offer for sale is positively associated with the price of the commodity. This is another way of saying that the quantity rises as price rises and the quantity falls as price falls. The reason is easy to find out.

The higher the price of a good the greater is the chance of making profit. Thus, the greater is the incentive to produce more and offer it for sale in the market. However, there are certain important exceptions to this type of producer behaviour.

We may now illustrate the relationship between price and quantity supplied with hypothetical data for a producer of carrots. The data can be presented either in the form of a schedule or a graph. Table 8.1 is a supply schedule of carrots.

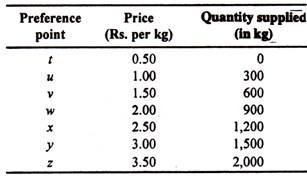

Table 8.1: A Producer’s Supply Schedule for Carrots

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It shows the quantities supplied at different prices. For example, nothing would be offered for sale when price is 50 paise per kg. If price rises to Re. 1 per kg, 300 kg will be supplied. If price rises to Rs. 1.50, 600 kg will be supplied, and so forth. Each price-quantity combination is shown by a reference letter as u, v, etc. for ready reference.

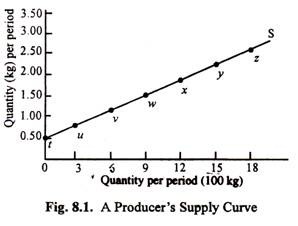

The data presented in Table 8.1 can be presented in the form of a graph as in Fig. 8.1. Both Table 8.1 and Fig. 8.1 give the same information. For example, points u, v, etc. in Fig. 8.1 show the same thing as the same points in Table 8.1. In fact Fig. 8.1 is a graphical representation of Table 8.1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The supply curve does not start from the origin. It starts from point t. In other words, the supply curve has an intercept. It cuts the vertical axis at a positive price. The implication is that there must exist a positive price for any quantity of a commodity to be offered at all. If price is less than this nothing will be offered for sale.

In this context Alfred Marshall referred to the reservation price of a commodity. In Fig. 8.1 a price greater than 50 p per kg is essential to produce and offer any output of carrots. If price were less than 50 p per kg, the minimum cost per unit could not be covered and output (quantity supplied) would be zero.

The smooth line through point’s t to z is the producer’s supply curve. Like the demand curve it is also the locus of alternative price- quantity combinations. It shows the different quantities offered for sale at seven different prices shown in the table as also at all intermediate prices.

For example, from Fig. 8.1 we can find out how much will be offered for sale at a price of Rs. 2.75 per kg. All we have to do is to locate the price on the vertical axis, draw a horizontal line from this point which cuts the supply curve at a particular point and then draw a perpendicular from that point. This point here indicates that when price is Rs. 2.75 per kg. the quantity offered for sale is 1,350 kg.

The Main Force behind the Supply Curve:

The supply curve is upward sloping, because the sellers normally feel that the higher the price of a commodity the larger the quantity that can profitably be offered for sale in the market place. We have already put forward a similar argument while accounting for the downward slope of the demand curve that consumers are willing to buy a large amount of a commodity when its price is low.

We noted that the demand curve of a commodity is downward sloping due to the operation of a fundamental psychological law, viz., the law of diminishing marginal utility. We also noted that a consumer reaches the point of maximum utility (or satisfaction) when, faced with the market price of the commodity, he buys that quantity at which the marginal utility of the last unit purchased is equal to its market price.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now we put forward a similar argument to account for the upward slope of the supply curve. The supply curve of a commodity is upward sloping due to the operation of the Law of Increasing Marginal Cost. Marginal cost increases due to the operation of a fundamental technological law of economics, viz., the Law of Diminishing (Marginal) Returns.

Each level of output that can be produced is associated with some level of cost. It is a matter of common knowledge that the larger the volume of output, the greater the total cost of production. In order to produce more output the producer has to use more capital and employ more workers. Both the factors have to be acquired at a cost (by paying their existing market prices).

So with an increase in the volume of output total cost rises (just as the consumer’s total utility rises with an increase in the consumption of a commodity). The extra cost associated with an extra unit of output is called marginal cost. It shows how fast costs rise with an increase in output. If, for instance, the total cost of producing 10 units of output is Rs. 300 and the total cost producing 11 units is 335, then the marginal cost, i.e., the cost of producing the 11th unit is Rs. 335 – Rs. 300 = Rs. 35.

In the short run the production capacity of the business firm remains fixed. Therefore, more output can be produced by using more of the variable factor. Labour is usually treated as the variable factor. However, as more and more workers are employed in the production process, keeping other factors constant, total product (output) increases no doubt. But marginal product falls. Every extra worker gradually makes less and less contribution to the total product of an enterprise.

This is due to the operation of the Law of Diminishing Returns, which is also known as the Law of Increasing Marginal Cost. Due to diminishing returns marginal cost rises, i.e., each unit produced adds more to total cost than the previous unit. Suppose the producer in our previous example decides to produce the 12th unit.

He observes that total cost increases from Rs. 335 to Rs. 375. So marginal cost is Rs. 40 which is higher than the marginal cost (MC) of producing the 11th unit (Rs. 35). Marginal cost rises because more and more pressure is created on the firm’s limited production capacity. Thus, the production process becomes less and less efficient with an increase in the volume of production.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A producer, whose objective is profit maximisation, will reach the optimum point when a condition is satisfied, i.e., marginal cost is equal to the given market prices of the product:

MC = P.

In fact, a consumer maximises utility when MU = P, i.e., when he equates his marginal utility of a commodity with its price. Thus the two rules of optimization are similar in nature.

Now what is the logic of the MC = P rule? Suppose, at the current level of output of a producer MC is less than P. This means that by producing and selling one extra unit he will add more to his sales revenue than to his cost. So he will have an extra incentive to produce one more unit of output and make profit. Thus, if the objective of the producer is to maximize profit he should increase his output when marginal cost is less than price.

Suppose, on the contrary, at the present level of output marginal cost exceeds price. This means that the last unit produced adds more to cost (MC) than it adds to his revenue (the price that he receives by selling it).

Thus he incurs a loss by producing the last unit of output. So it should not be produced. In other words, whenever MC exceeds price, extra output should not be produced. If output is reduced more money can be saved than earned.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So, when MC < P output should be increased and when MC > P, output should be curtailed. Thus it logically follows that only when MC = P there is no incentive to alter the volume of output.

We have just discovered how to derive producer’s supply curve. Since at the profit – maximising level of output MC = P, the MC curve of the producer is indeed the supply curve. In our previous example the MC of the 11th unit was Rs. 35 and the MC of the 12th unit was Rs. 40. If the market price of the product is Rs. 40, the producer would surely produce the 12th unit.

Thus as soon we come to know what is the producer’s MC, we can find out what will be produced at each market price. In fact, the supply schedule presented in Table 8.1 is the producer’s MC schedule. For example, the MC of producing 1,500 kg of carrots must have been Rs. 3. Otherwise the producer would not have produced 1,500 kg when the price was Rs. 3 per kg.

A profit-maximising firm will produce that level of output for which MC = P. The MC curve of a price-taking producer is indeed the supply curve. Since the MC increases with an increase in the volume of production, the supply curve is upward sloping (from left to right).

Other Determinants of Supply:

The quantity supplied of a commodity depends not only on its own price but on certain other factors as well. Here we assume that the price of the product under consideration remains constant. This enables us to consider the effects of other variables on supply.

We still remain the ceteris paribus assumption, i.e., while considering the effect of a particular variable we ignore the other influencing factors (assuming that they retain constant during the period under consideration). Or, in other words, we examine the effect of one variable at a time, keeping all other variables fixed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Other proximate determinants of supply are the following:

1. Prices of Other Goods:

Since resources have alternative uses, the quantity supplied of a commodity depends not only on its own price but also on prices of other commodities. So we have to consider the possibility of substitution in production.

If, for instance, the market price of wheat increases the jute farmers would probably switch over to wheat production without much difficulty. Thus, land may be diverted from jute to wheat in the event of a change in the relative price of the two products.

Here the absolute price of jute remains unchanged. But its relative price has fallen. On the other hand the relative price of wheat has increased due to a rise in its own (above) price. So more wheat and less jute will be produced by farmers (since land has alternative uses). Thus we see competitiveness in the production process.

We also see complementarily in production. There are certain commodities which, for technical reasons, are to be produced jointly such as sugar and khandsari, mutton and skins. Here the basic product is called the main product and the other is treated as the by-product.

Such products are said to be in joint supply. Thus a rise in the market price of mutton will increase the quantity of leather supplied. It is because the quantity of skin available for tanning into leather increases automatically with an increase in the output of mutton. Thus mutton and leather are jointly supplied.

2. Cost of Production:

Supply depends on cost of production. The producer’s decision to supply one extra unit is based on the concept of marginal cost. Therefore, any change in cost of production, other things remaining the same, will affect the quantity supplied of a commodity.

If cost of production increases the same quantity cannot be offered for sale unless the market price of the product also rises. This explains why there is a direct (positive) relation between price and quantity supplied of a commodity.

In fact, the supply schedule is another name of the MC schedule. Let us assume that in Table 8.1 the cost of producing carrot increases by 50 paise per kg at all level of output due to a rise in rent per acre or due to rise in agricultural wages.

If this happens the same quantity of carrot will not be offered for sale. Instead the quantity offered will now fall. For example, only 600 kg will now be supplied if price rises to Rs. 2.00 (= Rs. 1.50 + Re. 0.50). Similarly, 1,500 kg will be offered for sale if price rises to Rs. 3.50 per kg and so forth.

Production cost may rise due to the following two reasons:

(a) Changes in Factor Prices:

If the price of a factor of production (such as seed or fertiliser) rises, the cost of production (of carrot) will surely increase. If the market price of carrots remains constant (as per ceteris paribus assumption) production will be less profitable than before.

Thus the same quantity cannot be offered for sale at the same time. The quantity supplied will fall. A fall in the price of a factor will have an exactly opposite effect. If the price of picture tubes falls a larger quantity of TV sets may be offered for sale at the same price.

(b) Technological Change:

Cost of production depends not only on factor prices but on factor productivity as well. At a fixed point of time factor productivity (i.e., the ratio of output to input) remains constant due to unchanged technology (i.e., the art of production). But if we consider a long period of time we observe technological progress.

In fact, the recent fail in the market price of computers, hi-fi equipment, etc. is largely due to technological progress and not much due to the intensity of competition. No doubt, technological progress has been really spectacular in the electronics industry in the last two decades. In fact, at a fixed point of time, what an economy can produce and how it can produce desired goods and services largely depends on what is known. In the long run knowledge changes and with it the arts of production. Hence there are changes in supplies of commodities.

3. Objectives of Producers:

The quantity offered for sale also depends on the goal (objective) of the producer. The producer’s primary goal is profit maximisation. But this is not the only goal. There may be other goals as well.

A supplier may offer a large quantity of a commodity at a moderate price because he has a two-fold objective:

(i) high growth rate for its sales and

(ii) high profit.

So to capture the market in the long run, it can deliberately supply a large quantity at a low price in the short run. Thus some short-run profit may be sacrificed to make high profits in the long run. Similarly, the owner of a small retail store may prefer to see a TV serial on Sunday. Hence he may keep his shop closed just to satisfy his personal motive.

4. Producers Income:

Some small producers aim at a target profit or return per month. If the price of the product they sell rises they can offer a smaller quantity and still earn the same amount. Thus, in the event of a rise in market price, producers may decide to produce and sell less rather than more of a commodity.

5. Expectations about the Future:

Producers may and often do react to unexpected changes in any of the determinants of supply. If they can anticipate such a change they do react to it if, for instance, the market price of an item like cement is likely to rise after few months, producers will release less from their current stock.

They will withhold supplies for future sales at a higher price. If, on the other hand, techno-logical progress is likely to make a product (like a computer) obsolete in near future, the existing producers would decide to reduce the price of their products and clear the stocks as soon as they can.

6. Random Variables:

There are certain variables which are unsystematic or random in nature. But they do no doubt affect the quantity supplied of a commodity. Examples of such variables are – weather, plant disease, accident in a major industrial plant, or labour trouble in a major industry (such as India’s jute industry).

These are called external factors because they are outside the control of man. But they are very important from the point of view of supply of a commodity. For example, ceteris paribus, there may be a bumper crop of wheat in India due to good weather. On the other hand, frosts may destroy a portion of Brazil’s coffee crop.

7. Government Policy:

Various actions of the State such as taxes and subsidies, etc. may affect the aggregate supply of a commodity by influencing cost of production (i.e., marginal cost). Moreover, labour laws may affect productivity of labour and rules relating to smoke pollution may affect the types of boilers that may be used as also the location of the plant. The supply of a commodity like sugar or tea may be affected if there is fear of nationalisation or State take-over of the industry in not-too-distant future.

8. Non-Economic Factors:

Certain non- economic factors may also affect the supply of a commodity. These are of two broad categories, viz., social factors and psychological factors. Such factors include all those that have not been included in our list so far. These factors may include the state of business confidence, political considerations, etc.