The following points highlight the three taxes of the tax structure in developing countries.

1. Direct and Indirect Taxes:

Taxes are classified as direct or indirect. Indirect taxes are ones that are levied on goods and services and, thus, only “indirectly” on individuals.

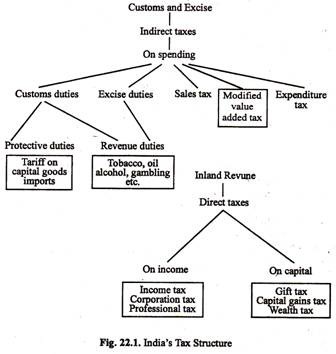

Examples are excise duties and sales taxes, import and export duties. By contrast, direct taxes are levied directly upon individuals or firms. Examples of direct taxes are personal income taxes, or capital gains tax and gift taxes. Corporation income taxes are also treated as direct taxes because people receive the income of corporations. See Fig. 22.1 which lists major taxes — direct and indirect.

Direct taxes are charged directly on the taxpayer’s income or wealth (capital). Indirect taxes are charged on expenditure and normally form part of the prices of goods and services when people buy them. In India they are collected by the Customs and Excise Departments. They are called indirect because, though they are normally collected from firms, the burden of payment is commonly shifted on to consumers when they make their purchases. The burden of direct taxes cannot usually be shifted to others in this way.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So a direct tax is one whose burden (or incidence) cannot be shifted. To put it in another way, in the case of direct taxes the impact and incidence are upon the same person the person who pays the tax cannot transfer the burden to any other person. The main examples of direct taxes are income tax, expenditure tax, wealth tax, gift tax, etc. The burden of these taxes falls upon the person on whom they are levied.

But there are certain other taxes whose incidence can be shifted. This is possible in the case of indirect taxes like the sales tax or the excise duty. The impact of sales tax is upon the seller of goods. But the seller is not required to pay the amount of the tax from his own pocket. He can easily shift the tax to the consumer from whom he gets the price of the article, and therefore, the incidence is upon the ultimate consumer.

Thus, it is the conjunction or separation of impact and incidence that makes a tax direct or indirect.

2. Proportional and Progressive Taxes:

Adam Smith stressed the principle of equality in tax levy. But how can this equality be achieved? According to Smith, equality is secured by taxing everyone at an equal rate. This is known as proportional taxation. Under this system, if a man with an annual Income of Rs. 100 pays Rs. 10 as tax, then a man with an annual income of Rs. 1,000 will pay Rs. 100. According to the classical economists, the levy of tax at a uniform rate on all persons secures equality of sacrifice.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But modern economists do not admit that a proportional rate of tax would secure equality of sacrifice. According to the modern view, the taxable capacity of a person increases more than in proportion to the increase of income.

In other words, with the increase in income, the taxable capacity increases at a rate more than what is proportional. Thus if a man with an income of Rs. 100 a year pays income tax at a rate of 10 per cent, then a person whose income is Rs. 1,000 a year ought to pay tax at a higher rate.

A progressive tax is one which charges different rates from different income-groups. Under this system, the higher the income the higher is the rate of taxation. Thus, if a man with an income of Rs. 10,000 a year pays 3% of his income as tax, a man with an income of Rs. 20,000 a year will have to pay 4%, 5% or more.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Progressive taxes are equitable because they make the rich people (who have greater ability) to pay more. The rates of a progressive tax can be so fixed as to secure equality of sacrifice between the rich and the poor. A tax is said to be regressive if it falls more heavily on lesser incomes. Commodity taxes like excise duty and sales tax are obvious examples. See the Table 22.2.

All modern mixed economies have adopted progressive taxation. Apart from seeming equality of sacrifice, it reduces disparity in income and wealth among the various classes of the people. In India, the income tax, wealth tax and gift tax are all progressive taxes.

3. Shifting and Incidence of Taxation:

The incidence of a tax is on the person who actually pays it. In the case of income tax, it clearly falls on the person earning the income. In the case of indirect taxes, however, the incidence may be on the buyer or the seller or it may be divided in any proportion between them depending on the elasticity of demand for the commodity on which the tax has been imposed.

The Distribution of the Tax Burden:

We may now discuss how an indirect tax is shared between consumers and producers.

When a good is subject to a sales tax, price will rise by less than the amount of the tax.

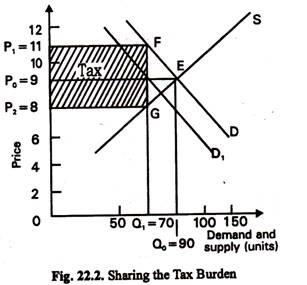

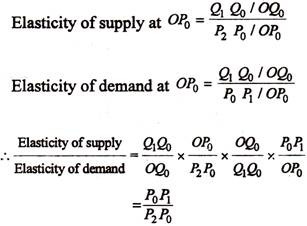

Thus in Figure 21.1 the tax is Rs. 3, but the price of X rises by only Rs. 2. The proposition is that the amount of the tax falling on consumers as compared with that falling on producers is directly proportional to the elasticity of supply as compared with the elasticity of demand.

Consumer’s shares of tax/Production tax = Elasticity of supply/Elasticity of demand.

When a tax is imposed, the reaction of the producers is to try to push the burden of the tax on to the consumer, while, similarly, the consumer tries to push it on to the producer. Who gains and who loses? Simply, the one whose bargaining position is stronger.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This will depend upon the ability to switch to producing substitutes if the price falls as compared with the ability to switch to buying substitutes if the price rises. Now the possibility of substitution largely determines elasticities of supply and demand. Thus the relative burden of the tax paid by the producers and consumers depend upon relative elasticities of supply and demand.

The proposition can be proved geometrically as follows:

As a result of the tax, price rises from OP0 to OP1, and the quantity demanded and supplied falls from OQ0 to OQ1 (Fig. 22.2).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Increase in price (burden of the tax) to the consumer

Increase in price (burden of the tax) to the consumer/Decrease in price (burden of the tax) to the producer

Application:

This proposition has the following practical applications:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) A tax on a good having an inelastic demand, e.g., cigarettes, falls mainly on the consumer.

(b) Where supply is inelastic compared with demand, the tax falls mainly on the producer?

(c) Because, in the long run, supply tends to be more elastic than in the short run, so, as time passes, the price will tend to rise as consumers are required to bear a greater share of the tax.

(d) Where supply is inelastic even in the long period, a tax will take longer to pass on to the consumer.

(e) An increase in price as a result of a tax will vary according to the relationship of elasticity of a supply to elasticity of demand. The greater the elasticity of supply relative to the elasticity of demand, the greater will be the price rise.