In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to the Leontief Paradox 2. Loentief Paradox and Evidence Related to Other Countries 3. Reconciliation 4. Criticisms.

Introduction to the Leontief Paradox:

The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem gave a generalisation that the capital-abundant counties tend to export capital-intensive goods while labour- abundant countries tend to export the labour- intensive goods. W.W. Leontief put this generalisation to empirical test in 1953 and found the results that were contrary – to the generalisation provided by the H-O theory.

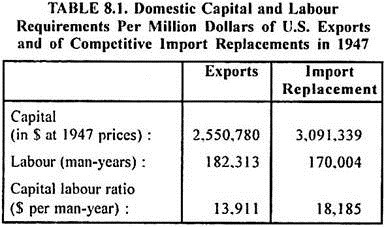

Leontief made use of 1947 input-output tables related to the U.S. economy. 200 groups of industries were consolidated into 50 sectors, of which 38 traded their products directly on the international market. He took only two factors of production— labour and capital. His main empirical results are stated in Table. 8.1.

Table 8.1, shows that import replacement industries in the U.S. had been employing 30 percent more of capital than the export industries. The capital-labour ratio was higher in the import- replacement industries than the export industries. It suggested that the exports of United States, generally recognised as the capital-abundant country, were labour-intensive.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Leontief therefore, concluded, “American participation in the international division of labour is based on its specialisation in labour intensive rather than capital-intensive lines of production. In other words, this country resorts to foreign trade in order to economize its capital and dispose of its surplus labour rather than vice-versa.”

In brief, capital-abundant countries export labour- intensive goods and labour-abundant countries export capital-intensive goods. This reflects what is called as ‘Leontief Paradox’ as this conclusion goes against H-O theory. Although the United States is a capital-abundant country, yet its specialisation is found in the labour-intensive commodities.

The conclusion derived by Leontief not only surprised himself but startled the academicians throughout the world. The economists undertook intense research for re-examining both the H-O theory and Leontief paradox. The attempts were also made on empirical grounds to reconcile the Leontief analysis with the H-O theory. Several economists investigated the causes of bias in Leontief’s work and exposed the methodological and statistical weaknesses and inaccuracies in his analysis.

Loentief Paradox and Evidence Related to Other Countries:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Loentief paradox brought into focus the crucial issue of the validity or otherwise of H-O theory. Many economists conducted Loentief type studies related to other countries. The evidence is, however, not conclusive one way or the other. While some of the empirical studies put a question mark on the validity of H-O theory, the others have gone in favour of it.

A study attempted by Tatemato and Ichimura concerning Japan has confirmed the Leontief paradox. Japan even though a labour-abundant country, imported labour-intensive goods like raw materials and exported capital-intensive goods such as automobiles, computers, T.V. sets, watches etc.

According to these writers, this pattern of trade is not consistent with the H-O theory. They attributed such a trade pattern to the fact that almost 75 percent of Japan’s exports were directed to the Third World countries which were more capital- scarce that Japan. From their viewpoint, Japanese exports to them were capital-intensive. In contrast to the United States, Japan was labour-abundant and capital-scarce. Consequently her exports to the advanced countries like the United States had a lower capital-labour ratio. In this way, their findings confirmed the validity of H-O theory.

The H-O theory found support from a study made by W. Stopler and K. Roskamp concerning the erstwhile East Germany in 1956. Almost 75 percent of her trade was with the countries of the communist block. East Germany was relatively more capital-abundant than the latter. At the same time, her exports to these countries were relatively capital- intensive and imports labour-intensive.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

D.F. Wahl conducted a study related to the trade pattern of Canada in 1961. This study showed that Canadian exports to the U.S.A, the major trading partner of Canada, were relatively more capital- intensive than her imports. It lent support to the Leontief paradox and contradicted the H-O theory.

Another study that provided support to the Leontief paradox was made by R. Bhardwaj in 1961 concerning India’s trade pattern. He showed that Indian exports, in general, were more labour- intensive, while imports were capital-intensive. However, in her trade with the United States, the exports were capital-intensive and imports were labour-intensive.

Thus, even this study ran counter to the H-O theory. There can be certain reasons for greater capital-intensity of exports by India and some other LDC’s to the United States. Firstly, these countries depend greatly on the technology imported from the advanced countries, as they do not themselves have an indigenous technology suited to their own factor endowments. The imported technology is highly capital-intensive.

As a result, the exported goods have a relatively high capital- labour ratio. Secondly, India relied heavily on the imports of food grains and many other consumer products from the United States until 1970’s. That accounted for high labour-intensity of her imports from the United States. Thirdly, there is a substantial direct foreign investment by MNC’s owned by the United States and the European countries in India and other LDC’s.

They generally operate in the export sector and produce goods through highly capital-intensive techniques. That can be one of the reasons for high capital-intensity of their exports, even though they are capital-scarce. Fourthly, there is factor price distortion in the LDC’s, i.e., the factor prices existing in these countries do not necessarily reflect their factor proportions.

There is the possibility that labour is over-priced and capital is underpriced in the LDC’s on account of such factors as strong trade union pressures, minimum wage laws, capital consumption allowances and other subsidies on capital and duty free imports of technology and capital goods from abroad. As the over-pricing of labour and underpricing of capital cause factor-price distortion, there is likelihood that the labour-surplus and capital-scarce countries like India export capital-intensive goods and import labour-intensive goods.

The Leontief paradox was supported by the study made by M. Diab in 1956 concerning the United States trade with Canada, Britain, Netherlands, France and Norway. This study, relying on Colin Clark’s data, demonstrated that the United States was having a low capital-labour ratio in her exports than the above-mentioned countries.

L. Tarshis approached the whole problem indirectly by comparing the internal commodity prices in different countries. The study revealed that the price ratio of capital-intensive relative to labour- intensive goods was lower in the United States and higher in other countries. Since the United States is a relatively capital-abundant country, the result is fully consistent with Heckscher-Ohlin theory.

In the empirical studies made by E.E. Leamer in 1980 and 1984, it is suggested that the comparison of K-L ratio in the multi-factor world should be in production versus consumption rather than in exports versus imports. Applying this approach to 1947 Leontief’s data, Learner concluded that K-L ratio was indeed greater in the United States production than the United States consumption. That strengthened the H-O theory and refuted Leontief paradox. The study made by Stern and Maskus in 1981 for the year 1972 confirmed the H- O theory even when natural resource industries were excluded.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In a 1987 study, however. Bowen, Learner and Sveikauskas, employed more complete 1967 cross- sectional data on trade, factor input requirements and factor endowments of 27 countries, 12 factors (resources) and several commodities. They concluded that H-O trade theory was valid in about fifty percent cases.

It is now sufficiently clear that the empirical studies concerning the Leontief paradox or H-O theory, have provided conflicting conclusions. Until convincing or more conclusive evidence becomes available in support of Leontief paradox, the H-O theory must be deemed as valid.

Reconciliation between Leontief Paradox and Heckscher-Ohlin Theory:

Although the conclusion given by Leontief was in contradiction to the generalisation given by H-O theory, yet Leontief never attempted to supplant the factor proportions theory. He rather tried to explain the reasons due to which he arrived at a result different from that provided by the H-O theory. Many other economists too attempted to reconcile the Leontief paradox with the H-O theory of international trade.

The more prominent explanations in this context are as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) Labour Productivity:

Leontief himself tried to bring about reconciliation between his paradox and H-O theory through the argument that the United States, though a labour-scarce country in strictly quantitative or conventional terms, is actually a labour-abundant country. The productivity of labour in the United States is about three times that of labour in the foreign countries. The higher productivity of the American labour was attributed by him to better organization and entrepreneurship in the United States than in other countries.

In view of this, it is not surprising that the labour- abundant United States exports those products, which have relatively greater labour-intensity. There is no doubt that the productivity of labour is higher in the United States than in other countries. But the multiple of three, as assumed by Leontief was clearly arbitrary. In a study conducted by Kreinin in 1965, it was revealed that the productivity of American labour was more than that of the foreign labour only by 20 to 25 percent and not by 300 percent.

Given such a situation, the United States cannot be regarded as a labour-abundant country. Salvatore pointed out that the higher labour productivity in the United States than in other countries implies a higher productivity of capital also in that country relative to the other countries. So both U.S. labour and capital should be multiplied by the same multiple 3. But that will leave the relative capital-abundance of the United States as unaffected. Leontief himself later on withdrew this explanation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Human Capital:

Leontief had found greater capital-intensity in the U.S. import- substitution industries than in export industries because he did not include the investment in human capital. He had emphasized only upon the physical capital such as machinery, equipment, buildings etc. The investment in human capital means spending on education, skill creation and health.

Such an investment brings about substantial increase in the productivity of labour. There is little doubt that the United States is most well-endowed with human capital. If the human capital component is added to the physical capital, the U.S. exports become far more capital-intensive relative to her import- substitutes. It is confirmed by the empirical studies conducted by Kravis (1956), Kenen (1965) and Keesing (1966).

(iii) Natural Resources:

In Leontief s analysis, the part played by natural resources in determining the composition of trade of a country had been over-looked. A prominent study made by J. Vanek showed that the United States was relatively scarce of several natural resources. There is complementarity between capital and natural resources in the field of production. The efficient utilization of capital requires large amounts of natural resources also. The United States imports, in fact, are the natural resource intensive products such as minerals and forest products.

These products have high capital- labour ratio in the United States process of production. By importing such products, the United States actually conserves her scarce natural resources. At the same time, she exports the farm products that have low capital-labour ratio. The exact assessment of the validity of H-O theory or Leontief paradox can be possible only after the quantification of the contribution of natural resources in a precise manner, gets materialised.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iv) Factor-Intensity Reversal:

The H-O theorem does not recognize the reversal of factor intensity. It assumes that a commodity cloth is labour-intensive both in the U.S.A. and India and another commodity steel is capital-intensive in both these countries. The factor-intensity reversal can occur if the United States produces and exports textiles through capital-intensive techniques but India produces and exports the same commodity though labour-intensive techniques.

In such a situation, the H-O theory cannot be sustained and Leontief paradox may become applicable in one of the two countries. But the factor-intensity reversal must be widespread or substantial to repudiate the H-O theory. A widely discussed study by Minhas recognised the validity of factor-intensity reversal but the studies made by Leontief himself in 1964 and Moroney found it to be quantitatively insignificant. It is found insufficient to reject strong factor intensity hypothesis of the H-O theory or justify Leontief’s paradox.

(v) Consumption Pattern:

Another explanation to reconcile the H-O theory and Leontief paradox is in terms of the consumption pattern in the U.S. economy. It is sometimes argued that the American consumption pattern was so strongly biased in favour of capital-intensive goods that the prices of such commodities were relatively higher in the United States and, therefore, she would export relatively labour-intensive goods.

This argument tends to support Leontief paradox. A 1957 study concluded by Houthakker about the consumption patterns in many counties showed that the income elasticity of demand for food, clothing, housing and several other goods was strikingly similar across nation. Consequently, the explanation of Leontief paradox in terms of taste differences cannot be accepted.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(vi) International Demand Pressures:

The high labour-intensity in the United States exports and capital-intensity in case of import-replacement products can be attributed to the demand pressures in the United States and her trading partners. Romney Robinson explained Leontief paradox without repudiating the Heckscher-Ohlin theory on the basis of relative patterns of demand existing in the United States and other countries.

According to him, the pattern of demand in the United States is such that it is compelled to import all such commodities that have a relatively higher capital-intensity. Similarly, the pressure of demand in foreign countries is such that the United States is required to export the labour-intensive commodities.

(vii) Research and Development:

Leontief arrived at a conclusion which is in contradiction to the H-O theory also because he over-looked the effect of research and development expenditure on the trade pattern. The value of output derived from a given stock of materials and human resources increases on account of research and development activity. Even casual observation demonstrates that the U.S. exports are research and development sensitive.

The study attempted by W. Gruber, D. Mehta and R. Vernon found that the U.S. export performance is closely related to the investment in research and development. It is true that this test is indirect, because technology differences have not so far been recognised as the basis for trade, but still the relative comparative advantages of different countries may be influenced by the research and development expenditure.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(viii) Tariff Structure:

Leontief paradox can be reconciled with H-O theory, if it is recognised that the tariff structure existing between the trading countries can influence the pattern of trade. A tariff is a tax on imports and it tends to restrict imports. A 1954 study made by Kravis showed that the labour-intensive industries were most heavily protected in the United States. That perhaps reduced the labour-intensity of U.S. import substitutes. Similarly the LDC’s may be compelled to permit duty-free import of agricultural products or other labour-intensive products from the United States in order to tide over their domestic shortages.

Criticisms of Leontief Paradox:

Leontief paradox has been subjected to criticism both on the methodological and empirical grounds.

The main objections against it are as follows:

(i) Inherent Bias:

The writers like B.C. Swirling and Salvatore found an inherent bias in Leontief s work related to year 1947. This year was very close to the period of Second World War (1939-45). The world economy, completely disorganised during the war-period, had not yet been able to make proper adjustments in production and international trade.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Inclusion of Industries with Low Capital-Intensity:

Swirling pointed out that the Leontief paradox involved a bias because of inclusion of certain industries in case of which capital-labour ratio was low. In view of this objection, Leontief reworked upon his data after enlarging the group of industries into 192 sectors. However, even this study confirmed that the American import- substitution industries had higher capital-intensity than the export industries, although the capital- intensity of the former over the latter had been reduced only to 6 percent.

(iii) Incompatibility of Input-Output Model:

The paradox was attacked by Valvaris-Vail on the ground that it was based on the input-output table showing the fixed input-output co-efficients. Such models are not compatible with the domestic conditions of international trade in which the technological developments do bring about changes in the input-output co-efficients and trade can have significant influence on the composition of production and structure of industries.

(iv) Problem of Aggregation:

According to Balogh, the Leontief paradox involved a bias that resulted from the aggregation in the input-output matrix for indirect computation of capital-labour ratio. A spurious labour-intensity of the U.S. export industry appeared because of the aggregation of capital-intensive exportable goods with similar domestically used labour-intensive goods.

(v) Irrelevant Factor-Intensity Comparison:

According to P.T. Ellsworth, the comparison instituted by Leontief between capital-abundant and labour-abundant countries in irrelevant. In fact, the comparison should have been made between the capital-intensity of U.S. exports with the capital- intensity in the countries from which the American imports are obtained.

The higher capital-intensity in import-replacement industries of the U.S.A. than her exports industries is also not surprising as the production of import substitutes in the U.S.A. is bound to require more capital per unit of labour due to more round-about methods of production there. Leontief should have seen whether or not goods imported into America were capital or labour intensive in the country of origin.

(vi) Neglect of the Role of Natural Resources:

Buchanan has criticized Leontief for having neglected the role of natural resources in the determination of trade pattern. This has also been stressed by E. Hoffmeyer and J. Vanek. Capital and natural resources are complementary in many fields of production. Although capital is relatively abundant in the United States, yet it may be less effective because that country is relatively under-supplied with natural resources and it may not be able to make full use of its capital. Larger agricultural exports from Canada, Australia and most of the less developed countries are land-intensive essentially because of an abundance of land.

(vii) Neglect of Differences in Durability of Capital:

According to Buchanan, Leontief made use of investment requirement co-efficient as the capital co-efficients. He failed to take into account the differences in capital durabilities in different industries.

(viii) Neglect of Human Capital:

Leontief’s conclusion suffered from bias that resulted from the inclusion of physical capital alone in his measure of capital. The human capital was overlooked completely. If human capital is included, the paradox gets eliminated. This was confirmed by several studies made by Kravis, Kenen and Keessing. Baldwin updated in 1971 Leontief’s study by using the 1958 U.S. input-output tables and U.S. trade data for 1962.

He confirmed Leontief paradox and found that the U.S. import-replacement industries were 27 percent more capital-intensive than the United States export industries. Baldwin pointed out that the exclusion of even natural-resource industries was not enough to repudiate the paradox. However, the inclusion of human capital could eliminate the paradox. But in fairness to Leontief, it must be said that the analysis of human capital became fully developed and fashionable only after the works of Schultz (1961) and Becker (1964) got published. .

(ix) Effect of Demand Conditions:

Romney Robinson attacked the Leontief paradox on the ground that the demand conditions within a country may be such that a country produces a commodity through the use of her abundant factor. The given demand or consumption pattern may prevent the export of such a commodity. On the opposite, the country may feel the necessity of importing it.

The capital-abundant country United States, on the basis of the above logic, may import capital-intensive goods from abroad, if its income level rises and if the income elasticity of demand for such goods in that country is high. Similarly, a labour-abundant country may export capital-intensive goods, if the income elasticity of demand for such goods is high in that country.

The Leontief paradox can be valid in the case of United States, if it is assumed that the consumption pattern in that country is very strongly biased in favour of capital-intensive goods. The assumption is, however, not acceptable. A study made by A.J. Brown revealed that the consumption or demand pattern in the United States did not appear to be biased in favour of capital- intensive goods. Thus Leontief paradox cannot be justified even on the basis of differences in demand or consumption pattern.

(x) Unbalanced Trade:

Learner expressed the view that Leontief paradox would fail when the country had trade imbalance. He pointed out that the United States had a trade surplus in 1947 and there was little evidence that exports were labour- intensive.

(xi) Analysis Concerned with Single Country:

Leontief arrived at the conclusion of higher capital- intensity of the U.S. imports than exports perhaps because his analysis was concerned with only one country—the U.S.A. Had he considered U.S.A along with Japan, he would have found that U.S. exports were capital-intensive compared with the Japanese exports.

(xii) Productivity of Labour:

Leontief attempted to defend his conclusion by putting forward the argument that the productivity of an average American worker was equivalent to three foreign workers. Therefore, the United States was a labour surplus country, which was likely to export labour- intensive goods. But Leontief failed to provide any convincing reason for making this rather arbitrary hypothesis.

In addition, the increase in labour efficiency or productivity to the stated extent implies that productivity of capital should also be three times more than that in the foreign country. The multiplication of capital stock with a multiple of three would leave the factor endowments unchanged and Leontief’s logic would fall through.

(xiii) Neglect of Tariffs:

A serious weakness in Leontief’s analysis was that he failed to take into account the effect of tariffs policy on the pattern of trade. W.P. Travis emphasized that the tariff policies adopted by different trading countries often distorted the pattern and composition of traded commodities. Leontief’s results too were seriously affected by tariff policies in the United States and her trading partners but Leontief overlooked this influence.

In view of objections against Leontief’s study and mixed empirical tests, a categorical answer about the validity of H-O theory or Leontief paradox cannot be easily given. “Clearly much more research,” says Sidney J. Wells, “remains to be done in this very intricate field; so far we really know very little about the precise relationship between any country’s pattern of trade and its factor endowments.”