Liquidity Preference Theory of Rate of Interest!

What is Liquidity Preference?

“Liquidity preference is the preference to have an equal amount j ^ of cash rather than claims against others.” -Prof. Mayers

Determination of Interest:

According to liquidity preference theory, interest is determined by the demand for and supply of money. It is determined at a point where supply of money is equal to demand for money.

Demand for Money:

To Keynes, money is not only a medium of exchange, but also a store of wealth. Now, there arises a question, why people want to hold cash?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to Keynes, there are three motives behind liquidity preference:

1. Transaction Motive:

According to Peterson, “The transactions motive relates to the need to hold some quantity of money balances (either currency or demand deposits) to carry on day to day economic dealings”. Most of the people receive their incomes by the week or month while the expenditure goes on every day.

Therefore, a certain amount of ready money is kept in hand to make daily payments. Not only individuals and households need money to meet daily requirements, but business firms also need it to meet daily transactions like the payment of wages, purchase of raw-materials and to pay for the cost of transport, etc.

The demand for money for transactions purposes depends upon various factors like income, the general level of business activity, and the interval at which income is received. For instance, if income is received after a long interval of time, a larger proportion of income will have to be kept in ready cash.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Similarly, where goods are available on credit, less amount of ready cash is needed. Thus, as a general rule, it can be said that the transactions demand for money is income elastic and may be expressed as

(Lt) = f(Y)

2. Precautionary Motive:

Every individual and firms keep their savings in liquid form for rainy days. Some part of the income is saved to provide for contingencies as illness in the family, a journey that may be required to be undertaken under compelling circumstances, some guests may arrive, some money is to be kept apart for some such event as birth or marriage, some friend or relative may require financial assistance.

For all such purposes, the person would like to keep money in liquid form or semi-liquid form, e.g., in savings bank. Liquidity preference for such motive is not as high as for the transaction motive. Nevertheless, there is some liquidity preference for precautionary motives.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This fact can be expressed in the form of an equation as:

Lp = f(Y)

According to Keynes, demand for money for precautionary motives depends on income. Keynes denotes M1, the combined demand for these two motives. Thus,

M1 = Lt+ Lp = f(Y)

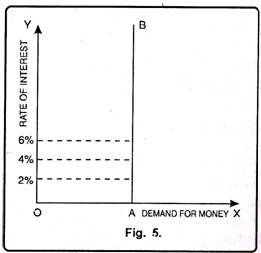

In Fig. 5 vertical line AB represents the demand for precautionary and transactionary motives. It signifies the fact that demand for money for these two purposes remains OA irrespective of any change in rate of interest.

3. Speculative Motive:

If a man has money that he can spare even after satisfying his consumption needs and after building funds sufficient to meet contingencies, he would like to invest money in such a way that brings him profits. In this case he would not be very keen for keeping his money in liquid form. The liquidity preference is low in such cases.

A high rate of interest can bring some money kept for precautionary motive for lending, but it will hardly be possible to bring out the money kept for transactional motive for lending. The more the money that is kept for the first two motives, the higher will be the rate of interest in the society and vice-versa.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It can be expressed in the form of an equation

M2 = f (r)

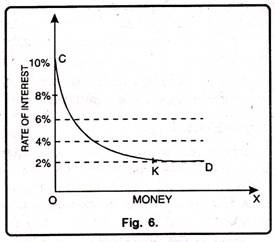

In Fig. 6 CD is the demand curve for speculative motives. It slopes downward from left to right. But at point K, it becomes parallel to X-axis. It indicates that demand for money is inversely related to rate of interest. In other words, at higher rate of interest, demand for money for speculative motives will be low and vice-versa.

Total Demand for Money:

The total demand for money (MD) in the summation of transaction, precautionary and speculative demand for money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

MD = M1 + M2 = f (Y, r)

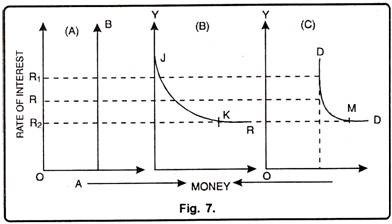

In Fig. 7 A transaction and precautionary demand for money is shown. AB is the demand curve which is perpendicular to X-axis. It indicates that rate of interest has no effect on it. In other words, with the increase or decrease in rate of interest demand for money remains stable.

In Fig. 7 B speculative demand for money is shown. JK is the demand curve which at point K becomes horizontal to X-axis; it signifies that rate of interest does affect the demand for money. At higher rate of interest demand for money is lower and vice-versa.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Fig. 7.C total demand for money is shown. It is the summation of transaction, precautionary and speculative demand for money. It is DD curve which at point M becomes horizontal to X-axis. This demand curve is known as liquidity preference curve.

Supply of Money:

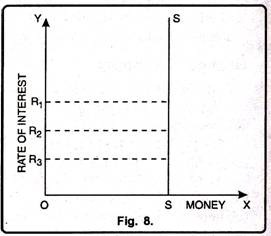

By supply of money is meant the sum total of currency and bank deposits held by non-banking public. The money supply in a country is determined by the monetary authority such as the central bank. Money supply is not related to the rate of interest.

It is the need of the economy which will determine the quantity of money. Therefore, the supply curve of money (M) is shown as a vertical line parallel to the ordinate (Y) axis as shown in Fig 8.

Equilibrium Rate of Interest:

According to Keynes, equilibrium rate of interest is determined at a point where demand for money is equal to supply of money.

MD (LP) = MS.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

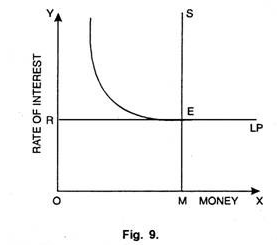

In Fig. 9 MS is the supply curve of money where LP is the liquidity preference or demand curve for money. Both these curves intersect each other at point E which determines OR rate of interest.

However, effect of change in demand for money and supply of money are explained as under:

Change in Demand for Money:

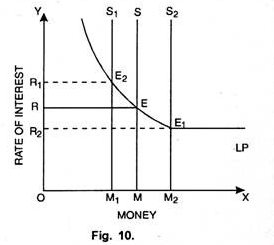

If the supply of money remains constant, and as the liquidity preference for money increases rate of interest also increases and vice-versa. In Fig. 10. SM is the supply of money curve. M, M1, M2 are the demand for money curves. Now suppose that initially M is the demand curve. Here equilibrium is restored at point E where M curve cuts MS and rate of interest is determined.

If liquidity preference increases to M1, new equilibrium will be at E1 and the interest rate increases to OR1. If contrary to this, liquidity preference curve falls to M2, equilibrium will be at point E2 which will determine OR2 interest rate.

Change in Supply:

If demand for money remains constant, as the supply of money increases, rate of interest decreases and vice-versa.

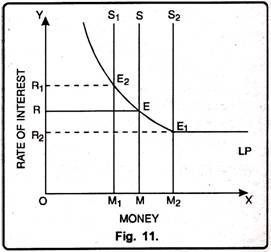

In Fig. 11 LP is the liquidity preference curve while MS, M1S1 and M2S2 are the supply curves. In the beginning, MS is the supply curve which intersects demand curve at point E. Here equilibrium rate of interest is OR.

Now if the supply of money decreases to M1S1, then LP curve cuts supply curvy at E2. The equilibrium rate of interest is OR1. On the other hand, if supply of money increases to S2 M2, equilibrium interest rate falls to OR2.