Here we detail about the five important implications of liquidity preference theory by Keynes.

(a) Rate of Interest and Supply of Money:

The Monetary authority under Keynesian economics is expected to stimulate employment by following a cheap money policy, i.e., of lowering the rate of interest by increasing the supply of money.

The idea behind an easy money policy is that an increase in the total supply of money (other things remaining the same) will increase the money available for speculative motive (M2) thereby causing a fall in the rate of interest, and stimulating investment, which in turn, will increase income.

“How effective monetary stimulation will be depended on how much the rate of interest falls in response to an increase in M2 (upon the elasticity of the L% function); how responsive investment is to a fall in the rate of interest (the elasticity of the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital); and how much a given increase in investment will increase income (the size of the investment multiplier)”. But such a policy of monetary management is beset with important limitations. An increase in the quantity of money (other things remaining the same) will lower the rate of interest, it will not do so if the liquidity preference is increasing more than the quantity of money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Similarly, a fall in the rate of interest (other things remaining the same) will increase investment and employment but it may not be so if the marginal efficiency of capital is declining more than the rate of interest. When an economy is passing through the depths of chronic depression, when liquidity preference is high and expectations of profitability low, monetary policy may prove quite ineffective to break the economic deadlock. Thus, from the practical point of view monetary policy as based on Keynes’ liquidity preference analysis encounters serious limitations.

(b) Expectations and the Rate of Interest:

Another implication of the liquidity preference theory of the rate of interest is about the important role played by expectations. In fact, our understanding of the LP theory is not complete without taking into consideration the role of expectations, specially the expectations held by the individuals and business firms concerning future economic values of bonds and securities. Certain basic features of the asset and speculative demand for money can be properly understood through reference to expectations. We have already seen that uncertainty with respect to the future is the main reason why some persons prefer to hold money rather than income yielding assets.

This is logical but not enough. Expectations as to the future economic values provide the basic explanations as to why individuals and firms shift from money to debt or bonds and vice versa. Expectations concerning future prices and the behaviour that follows from such expectations has meaning only in relation to notions about what constitutes a normal level of bond prices or interest rates. Given the notion of a normal rate, if wealth holders view the current rate as high, they then expect a drop in the rate as it returns to normal.

At this high rate, asset holders will discard cash and hold bonds. If, on the other hand, asset holders expect the current rate as low, they anticipated a rise in the rate as it returns to normal. As such, they discard bonds and hold cash. Equilibrium will be reached where bearish expectations in the market are counter-balanced by expectations that are bullish. The introduction of both the bond market as well as expectations with regard to future value into our analysis provides us with a much fuller explanation of the shape of the asset demand curve.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Once we understand the relationship between asset demand, bond market and the role of expectations, it is possible to see that much more is involved in the demand for money than simply the cost of holding it. This relationship provides the basis for an explanation of an interesting phenomenon described as the liquidity trap, discussed further.

The Radcliffe Committee Report points out that the expectations in the movement in interest rate could have two types of effects:

(i) The incentive effect,

(ii) The general liquidity effect.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The incentive effect refers to expected changes in the rate of interest, that is, cost of money influencing the cost of holding stocks of goods—whether commodities or capital goods. With the expectation of a rise in the rate of interest the stock holder or the investor would like to cut back on account of the increased cost of holding the stocks or taking up the venture.

This is interest incentive effect which pays attention to the cost of money in holding goods, etc. But Radcliffe Committee observes that the cost of money is relatively small in comparison with other costs of production and that it has little or no effect on holders or investors to change their plans. Because the capital investment is often decided by the costs of materials of the availability of labour and not by the rate of interest.

The general liquidity effect, on the other hand, pertains, to the expected behaviour of lenders rather than borrowers. It refers to the liquidity position of the near money asset-holders due to changes in the value of such financial assets. As a result of the expected effects of changes in the rates of interest on the prices of such assets: the behaviour of lenders undergoes a change, which in turn, may influence the credit availability in the money market.

Thus, when the interest rates go up, the lenders find that the value of their financial assets has dropped, and they are less ready to lend more cash to borrowers. The report says that from the evidence it seems that the general liquidity effect of the rate of interest has a little more weight than the interest incentive effect.

(c) Inverse Relationship between the Rate of Interest and Bond Price:

Another implication of the liquidity preference theory as given by Keynes is that bond prices are inversely related to interest rates. In other words, bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions, i.e., when interest rates fall, bond prices rise and when interest rates rise, bond prices fall.

Suppose a bond pays a fixed income of Rs. 50 per year at 5% rate of interest and sells at Rs. 1,000 in the market. Now, if the rate of interest falls to 4%, the price of bond will increase to Rs. 1,250 in order to earn an income of Rs. 50 a year. Similarly, if the rate of interest rises to 6% the price of the bond will fall to about Rs. 850 to give us a fixed income of about Rs. 50.

The formula for the same is:

Bt + iBt = Bt( 1 + i) = Bt + 1

where B, is the purchase price of the bond, i represents the interest rate, Bt +1 represents the redemption value of the bond after one year of its purchase. Therefore, if the purchase price of the bond is Rs. 100 and the interest rate is 6 per cent, the redemption price of the bond is Rs. 106. Now, suppose the redemption price of the bond is given at Rs. 106, and the interest rate is also given at 6 per cent— the current purchase price of the bond—Bt is.

Now, assume the interest rate on bond falls from 6 per cent to 4 per cent per annum, during the current year, while the rate of interest on the old bond remains—at 6 per cent. The new purchase price of the old bond (assuming the yield on old bond at Rs. 6) will be:

It is, therefore, clear that as the rate of interest falls, bond prices rise and vice versa. Hence, the price of a bond and the rate of interest are inversely related. Changes in the prices of bonds in the organized securities markets reflect themselves in the changes in the liquidity preference of the people. A decline in liquidity preference is reflected in an increased desire on the part of the public to buy bonds at current prices raising the prices of bonds and lowering the rate of interest.

On the other hand, an increase in the liquidity preference is reflected in an increased desire on the part of the public to sell bonds to get more cash, as a result of which prices of bonds will fall and interest rates will rise. Thus, we find an inverse relationship between the prices of bonds and the interest rates.

(d) Long-Term versus Short-Term Rate of Interest:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A distinction between the short-term and the long-term rate of interest constitutes an important implication of Keynes’ liquidity preference theory. Interest is a reward for parting with liquidity and is given to the wealth holder who surrenders control over money (liquidity) in exchange for a debt, bond or a security. The rate of interest (reward for parting with liquidity) differs on debts of varying lengths and maturities. The rate of interest on daily loans will he different from the rates of interest on weekly, monthly or yearly loans.

Debts of longer maturity like three, five or ten years will have different rates of interest. Although these rates of interest vary in amount, “they are all of the same species”. For the sake of convenience, understanding and simplicity, we do speak of the rate of interest without mentioning debt of any particular maturity. This, however, does not mean that what really exists in the market is not a complex structure of rates of interest. In order to overcome this difficulty, a distinction is made between the short-term rate of interest paid on bank loans and the long-term rate of interest paid on bonds and securities.

Since the speculative demand for money over a short period changes very violently, the short-term rate of interest is subject to greater violations than the long-term rate of interest. The long-term rate of interest is comparatively stable because over a long period, expectations of conflicting nature cancel themselves out leaving very little influence on the rate of interest. In Keynes’ theory, however, real investment in durable capital assets play an important role and makes the long-term rate of interest on loans, bonds and securities, used to finance these investments of primary significance.

It may be noted that it is much easier to bring down the short-term rate of interest than long-term interest rate, as the commitments on the former type do not result in huge losses even if expectations prove wrong. Thus, a distinction between the short-term and the long-term rates of interest has important policy implications.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The short-term and the long-term rates of interest move in the same direction. If long-term rates of interest tend to rise and the short ones do not, a difference in interest earnings will result. Some borrowers who had previously been borrowing long will now decide to borrow short. On the other hand, some lenders will decide to lend long. This will go on until the long and short rates establish the previous relationship through a fall in the capital value of short-term bills (i.e., a rise in short-term interest rates) and the rise in the capital value of bonds or long-term bills (i.e., a fall in long term rates of interest).

Most of the borrowers and lenders, it has generally been seen, cannot remain indifferent to the long and short rates markets even when the returns or costs in the two markets are the same. Because, the bill-holders are less certain about returns while bond-holders are less certain about the value of their assets. Thus, the divergence between the two rates disappears through the forces of shift of most of the lenders and borrowers from one market to the other.

Specifically, when the interest rate on long-term debt falls to a level that wealth holders regard as below normal—there will be a shift into interest bearing short-term debt, rather than into non-interest bearing cash. The rise they expect in the long-term interest rate will mean a capital loss on holdings, of long-term debt, but this does not necessarily mean that they will choose to hold more money as Keynes had postulated—they can avoid the capital loss and still earn an interest return by holding short-term debt.

Two distinct views have been expressed by Hawtrey and Keynes regarding the operation of the rate of interest and its influence on investment and economic activity. According to Hawtrey these are influenced by changes in the short-term rate of interest, while Keynes expressed the opinion that these are mainly influenced by changes in the long-term rate of interest. Hawtrey holds that movements in the short-term rates of interest effects income, output and employment through their influence on the stock holders activities like traders or dealers who keep stocks of goods with borrowed money.

Should the short-term rate of interest go up, they will reduce the stocks because the cost of holding has increased. This view of Hawtrey has been criticised because it gives undue importance to the activities of stock holders and to the rate of interest as the cost of holding such stocks—whereas it is only one factor in the total cost. Keynes considers the effect of long-term rate of interest on investment.

(e) The Liquidity Trap:

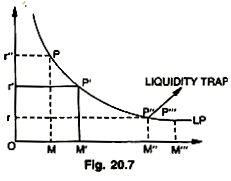

A close scrutiny of liquidity preference schedule in the figure brings forth another important implication of the liquidity preference theory by showing the behaviour of the demand for idle cash balances in response to decline in the interest rate. It shows as the interest rate falls (from Or “to Or’ to Or), the LP curve becomes more and more elastic, until finally, it becomes perfectly elastic.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It shows that the rate of interest is more difficult to lower and becomes increasingly resistant to further reduction at every step on its downward path, where the demand for money becomes perfectly elastic. For example, after or rate of interest, no further reduction in the rate of interest may be possible. The reason for this is the increasing risk of loss in the interest income at lower rates of interest. Moreover, the low interest rate does not adequately compensate for the incidental expenses and inconvenience of buying bonds.

Further, there is reason to expect that if bond prices change at all, they must decline. For all these reasons, the liquidity preference curve becomes perfectly elastic showing that no further reduction in the rate of interest is possible merely by increasing the quantity of money; for example, in Fig. 20.7, no further reduction in the rate of interest is possible after Or even though the quantity of money is increased from OM to OM”, rate of interest remains the same (Or = P”M” – P'”M'”).

When this stage is reached, the demand for money has become absolute in the sense that everyone prefers to hold money rather than bonds or securities yielding a return of Or (interest) or less. Since bonds and securities are no longer purchased with added money (A/”A/'”), bond prices will not be raised and the interest rate is trapped at Or. Suppose a security of the value of Rs. 1,000 brings a fixed income of Rs. 20 a year at 2% low interest rate.

Now, suppose the rate of interest changes from 2% to 3%, as a result of this, the value of security will fall to about Rs. 670 (because this sum will bring the fixed income of Rs. 20 a year) thereby causing a loss of Rs. 330. It is to avoid such a loss in the value of bonds and securities that people like to keep more cash at a low rate of interest.

This is because people are more or less convinced that the rate of interest has fallen to the minimum and do not expect it to fall further. If at all they expect any change, it is in the upward direction (as from 2% to 3% in the above example), causing a fall in the prices of bonds. It is, therefore, clear that on account of psychological and institutional rigidities, the rate of interest becomes sticky (near-about the level of 2% and does not or cannot) fall to zero or become negative.

A conclusion that can be drawn from this (liquidity trap) feature or liquidity preference is that the rate of interest is not likely to fall below a certain level (say 2%). From the practical point of view, it means that it is not even desirable or possible to depress it below that level, even though such a fall may be warranted in the public interest. In other words, it means that the rate of interest cannot fall to zero and if it does not fall to zero, it cannot become negative.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

J.R. Hicks, however, does not agree with the explanation given by Keynes as to why the rate of interest cannot fall to zero. According to Prof. Hicks, the chief reason (as to why the rate of interest cannot fall to zero) is not the uncertainty regarding the rate of interest at low levels but the basic quality of money as being most liquid. Money being the medium of exchange, if kept in the form of ready cash (liquid form), can be put to any use, whereas if kept in the illiquid form (bonds and securities) it cannot be readily put to any kind of use, unless the cost and inconvenience to turn the same into cash have been incurred.

The demand for and supply of money is different from the demand for and supply of a commodity. An excess of supply over demand of a commodity may cause its price to fall to zero but excess of money over its demand will not cause its price (interest) to fall to zero; for, as long as money is the only important medium of exchange to obtain goods and services to satisfy our unlimited desires, it is bound to be demanded and carry a price (interest) even though at a lower rate. In any case, interest cannot fall to zero. Hicks explanation as to why the rate of interest cannot fall to zero is considered more satisfactory than Keynes’ by some economists.

Even in the neo-classical loanable funds version—as long as the demand for funds is more than supply the rate of interest is bound to be positive. Some economists have argued that on account of improved standard of living of the people in Western countries accompanied by rising incomes, a stage may come that the supply of funds as a result of high accumulation will exceed the demand for funds and this surplus supply of capital may reduce its marginal productivity to zero. But this is not possible because the demand for capital is not going to lag behind its supply.

Increasing population pressures, changes in tastes and techniques of production are factors which are likely to keep the demand for loanable funds high and as such there is no possibility of the rate of interest falling to zero—because the basic feature of capital—scarcity is bound to be there.