There are as many elasticity’s of demand as its determinants.

The most important of these elasticity’s are:

(a) The price elasticity,

(b) The income elasticity,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) The cross-elasticity of demand.

The price elasticity of demand:

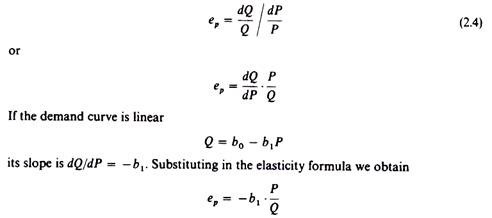

The price elasticity is a measure of the responsiveness of demand to changes in the commodity’s own price. If the changes in price are very small we use as a measure of the responsiveness of demand the point elasticity of demand. If the changes in price are not small we use the arc elasticity of demand as the relevant measure. The point elasticity of demand is defined as the proportionate change in the quantity demanded resulting from a very small proportionate change in price. Symbolically we may write

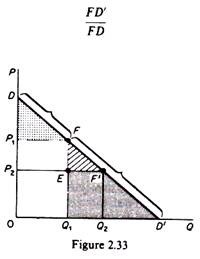

which implies that the elasticity changes at the various points of the linear-demand curve. Graphically the point elasticity of a linear-demand curve is shown by the ratio of the segments of the line to the right and to the left of the particular point. In figure 2.33 the elasticity of the linear-demand curve at point F is the ratio

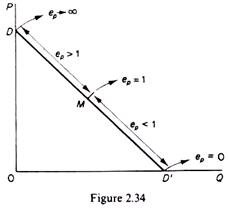

Given this graphical measurement of point elasticity it is obvious that at the mid-point of a linear-demand curve ep — 1 (point M in figure 2.34). At any point to the right of M

the point elasticity is less than unity (ep < 1); finally at any point to the left of M, ep > 1. At point D the ep → ∞, while at point D’ the ep = 0. The price elasticity is always negative because of the inverse relationship between Q and P implied by the ‘law of demand’. However, traditionally the negative sign is omitted when writing the formula of the elasticity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The range of values of the elasticity is

0 ≤ ep ≤ ∞

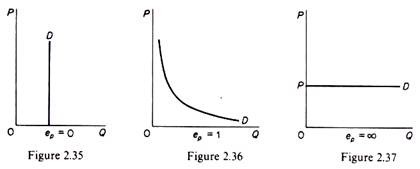

If ep = 0, the demand is perfectly inelastic (figure 2.35)

If ep = 1, the demand has unitary elasticity (figure 2.36)

If ep = ∞, the demand is perfectly elastic (figure 2.37)

If 0 < e < 1, we say that the demand is inelastic.

If 1 < e < ∞, we say that the demand is elastic.

The basic determinants of the elasticity of demand of a commodity with respect to its own price are:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(1) The availability of substitutes; the demand for a commodity is more elastic if there are close substitutes for it.

(2) The nature of the need that the commodity satisfies. In general, luxury goods are price elastic, while necessities are price inelastic.

(3) The time period. Demand is more elastic in the long run.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(4) The number of uses to which a commodity can be put. The more the possible uses of a commodity the greater its price elasticity will be.

(5) The proportion of income spent on the particular commodity.

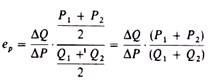

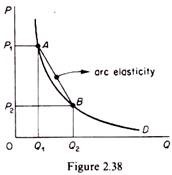

The above formula for the price elasticity is applicable only for infinitesimal changes in the price. If the price changes appreciably we use the following formula, which measures the arc elasticity of demand

ADVERTISEMENTS:

They are elasticity is a measure of the average elasticity, that is, the elasticity at the midpoint of the chord that connects the two points (A and B) on the demand curve defined by the initial and the new price levels (figure 2.38). It should be clear that the measure of the arc elasticity is an approximation of the true elasticity of the section AB of the demand curve, which is used when we know only the two points A and B from the demand curve, but not the intermediate ones. Clearly the more convex to the origin the demand curve is, the poorer the linear approximation attained by the arc elasticity formula.

The income elasticity of demand:

The income elasticity is defined as the proportionate change in the quantity demanded resulting from a proportionate change in income. Symbolically we may write

The income elasticity is positive for normal goods. Some writers have used income elasticity in order to classify goods into ‘luxuries’ and ‘necessities’. A commodity is considered to be a ‘luxury’ if its income elasticity is greater than unity. A commodity is a ‘necessity’ if its income elasticity is small (less than unity, usually).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The main determinants of income elasticity are:

1. The nature of the need that the commodity covers the percentage of income spent on food declines as income increases (this is known as Engel’s Law and has sometimes been used as a measure of welfare and of the development stage of an economy).

2. The initial level of income of a country. For example, a TV set is a luxury in an underdeveloped, poor country while it is a ‘necessity’ in a country with high per capita income.

3. The time period, because consumption patterns adjust with a time-lag to changes in income.

The cross-elasticity of demand:

We have already talked about the price cross-elasticity with connection to the classification of commodities into substitutes and complements (see section I).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The cross-elasticity of demand is defined as the proportionate change in the quantity demanded of x resulting from a proportionate change in the price of y. Symbolically we have

The sign of the cross-elasticity is negative if x and y are complementary goods, and positive if x and y are substitutes. The higher the value of the cross-elasticity the stronger will be the degree of substitutability or complementarity of x and y. The main determinant of the cross-elasticity is the nature of the commodities relative to their uses. If two commodities can satisfy equally well the same need, the cross- elasticity is high, and vice versa. The cross-elasticity has been used for the definition of the firms which form an industry.