The Shape of the Individual Firm’s Demand Curve:

The analysis of the previous section was concentrated on the aggregate demand for consumers’ goods.

However, for the theory of the firm and the understanding of the decision-making process of the firm we must look at the demand for the product of the individual firm.

Consumers’ demand is a small fraction of the aggregate demand for manufacturing products. The majority of manufacturing commodities is sold to other businesses, other firms for further processing, or to traders (wholesalers and retailers).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Even if the firm produces final consumers’ goods, it seldom sells them directly to the consumers. Most products reach the consumer through a retailer. Traditional economic theory has ignored the distribution methods of the commodities produced and their effect on the pricing policy of the firm.

Furthermore, traditional theory has ignored the distinction between short-run and long-run demand. The long run is not defined from the standpoint of demand, as it is from the standpoint of production and costs. It is usually stated that in the long run demand is more elastic than in the short run, but the time periods involved in this statement are left in obscurity. In traditional economic theory the shape of the demand curve of the firm is different in various market structures.

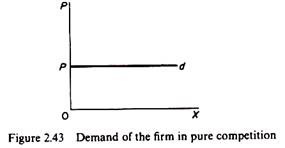

In pure competition the demand of the individual firm is perfectly elastic (figure 2.43). This shape is the consequence of the assumptions of the purely competitive model, the assumptions of an homogeneous product and of large numbers of sellers. In pure competition the firm, however large, offers a small part of the total quantity in the market and hence it cannot affect the price. The firm is a price-taker. The market price is determined by the market supply and demand functions and at this price the firm can sell any quantity it wishes.

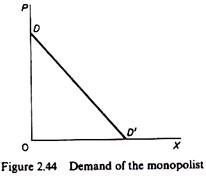

In monopoly the firm’s demand is the demand of the industry, and the monopolist decides his price and output on the basis of the market demand which is downward-sloping, obeying the general ‘law of demand’ (figure 2.44).

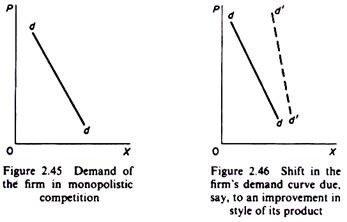

In monopolistic competition the demand of the individual firm is downward-sloping, as is the market demand. Chamberlin was the first economist who stressed the multivariate nature of the demand of the individual firm. He postulated that as a consequence of product differentiation the firm has some freedom in setting its own price. Each firm has its own customers, who have a preference for the firm’s products.

To strengthen the preferences of consumers and secure its market the firm pays particular attention to the style and quality of its product. Furthermore the firm undertakes advertising and other selling activities in an attempt to enlarge its market (shift its demand outwards) and make its demand more inelastic. Thus the demand for the product of a firm is multivariate

dt = f(Pl, Po ,P ,Al, A0, Si S0,Y, t,…)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Where di = demand of the ith firm

Pi = price of the ith firm

P0 = price of competitors

P = price of other commodities

Ai = advertising and other selling expenses of the ith firm

A0 = advertising and other selling activities of competitors

Si = style of the product of the ith firm

S0 = style of the product of other competitors

Y = consumers’ income

ADVERTISEMENTS:

t = consumers’ tastes

The firm’s demand curve (figure 2.45) is drawn under the usual ceteris paribus assumption : it shows the quantity demanded of the product of the ith firm at different prices charged by the firm given the style of the product, the selling activities, and so on. If any one of these factors changes, the demand for the product of the firm will shift (figure 2.46).

The main criticism against Chamberlin’s demand function is that it refers only to the demand of final consumers, thus ignoring the other buyers of the product of a manufacturing business, as well as the channels of distribution of the commodities. Some writers have argued that Chamberlin’s demand curve is valid only for the short run; in the long run the demand curve cannot have a negative slope, because this would imply irrational preferences of the consumers. We think that this criticism implies a special definition of rational behaviour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In particular it is implicitly assumed that consumers are irrational if they pay a higher price for technically identical or very similar products. This definition of rationality is too narrow.The rational consumer aims at the maximization of his utility or satisfaction. What gives him a higher satisfaction is a purely subjective matter. If the shopping from a ‘trendy’ shop gives the consumer a ‘conspicuous’ satisfaction despite his having to pay a higher price for the same (or very similar) commodities, surely one cannot say that the consumer behaves irrationally. He would be irrational if he adopted a course of action inconsistent with his preferences.

In oligopolistic models various shapes of the firm’s demand curve have been adopted. It is generally agreed that there is great uncertainty regarding the demand curve of the oligopolist, due to the interdependence of competitors and the uncertainty as to their reaction to any particular decision of a firm within the group. Some writers have made specific assumptions about the competitors’ reactions and have drawn a downward-sloping demand curve for the firm based on the assumptions they made.

Other writers have based their analysis on a market-share demand curve. This individual demand curve is derived from the market demand curve (which is assumed to be known) on the assumption that the firm keeps a constant share of the market at all price levels. The constant-share demand curve has the same elasticity as the market- demand curve at all prices.

Some economists have assumed a ‘kinked’ shape of the firm’s demand curve. The kink implies that the firm expects that its competitors will follow suit with price cuts, but not price rises. Thus to the left of the kink the demand curve has a greater elasticity than at points to the right of the kink.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Other economists have developed their models using a long-run demand curve which is very elastic without, however, attempting to define the determinants of this demand, or the time dimensions of their analysis. It has been argued in economic literature that the uncertainty surrounding the demand curve of the individual firm is so great that it has little or no relevance as a tool of analysis in the decision-making process in a firm. Finally, several modern theorists have taken the firm’s demand as given, on the grounds that interdependence is largely ignored in the day-to-day decisions of the firm.

The widely differing views stem from a widespread confusion between the demand curve and the demand function. The demand curve depicts the relationship between the quantity demanded and the price of the product of the particular firm under the ceteris paribus clause, while the demand function includes all the determinants of the demand which may change simultaneously.

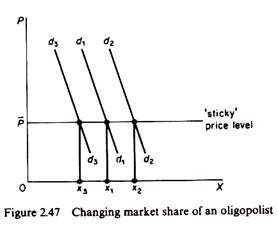

The fact that prices in some oligopolistic markets are sticky (except when rising costs render price increases inevitable) has been interpreted mistakenly as implying the non-existence of the individual demand curve. Yet the fluctuation of sales at the prevailing (sticky) market prices suggests that some of the other determinants of the demand function caused the demand curve to shift.

The observed constancy of price implies that we cannot measure the price elasticity of the firm’s curve, and the changes in sales must be attributed to the change in some of the other determinants of demand. These determinants will be better understood if we examine the sources of demand of the firm, that is, the buyers of the typical manufacturing business.

Sources of demand for the product of a firm:

In the modern business world the typical buyer of a firm is another firm and not the consumer as the traditional theory accepted. Even in the case of a firm producing consumer goods, the firm markets its products through wholesalers and retailers (in most cases). These intermediaries are profit-seeking enterprises and hence behave in a different way than the consumer. Let us examine in detail the probable shape of the demand of the various types of buyers of a manufacturing firm.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The final consumers:

It has been argued by some writers that in the long run the demand of consumers (for the product of a firm) will not be downward sloping for technically identical or very similar products, because this would imply irrational preferences. Consumers’ preferences, they argue, are not sticky in the long run. Consumers’ tastes change continuously over time, and even the same person, if he is rational, will try the cheaper products and change his supplier in the long run. We do not agree with this reasoning.

It is an observed fact that different brands of commodities are sold at different prices and still keep their market share over periods that may by any standard be considered long (ten or twenty years). This may be due to habit persistence, inertia, incomplete knowledge, conspicuous-consumption effects, and other reasons. Whatever the cause, it remains a fact that very similar commodities are sold over long periods of time at different prices.

Thus consumers’ preferences for particular brands are persistent and give rise to a demand curve with a negative slope. This is more so for consumer durables, where the amounts of money involved in each item are substantial for the household. In these cases the choice of the consumer is mostly based on brand names and on information of friends and relatives who have already tried the products and have acquired experience about their quality.

Other manufacturing firms:

Here we must distinguish between investment goods and intermediate goods which will be used as parts of the product of the buying firm. Regarding investment goods, brand names play an important role. Machinery and other equipment involve large expenditures and are to be used for a considerable time period. Thus the investing firms will be expected to have a strong preference for the machinery supplied by well-established firms even if they have to pay a higher price.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This behaviour will give rise to a negatively-sloping demand curve for investment goods. For intermediate commodities, however, which are often standardized, no firm will be prepared to pay a higher price if it can buy them from another supplier at a lower price. Thus, for firms who produce standardized intermediate products the demand curve will be infinitely elastic, not only in the long run but also in the short run. The market share of such firm-suppliers will be determined by factors other than the price, such as prompt delivery and ‘good service’ in general.

Wholesalers:

Wholesalers are profit-seeking businessmen and can affect to a certain extent their customers’ demand by their stock policy. They will prefer to buy and stock (in order to resell) commodities on which their profit margins are larger, that is, products which, though similar to others, can be bought at a lower price.

However, we believe that their discretion is limited. If they are wholesalers of final commodities, surely they can pass on to their customers a higher price if they have a strong demand for a product, thus keeping their profit margins at the desired level. If they are wholesalers of intermediate goods which are of standard specifications, they will not be prepared to pay a higher price for goods technically identical, because they can influence their buyers by offering the cheaper products, even if the brand is not as yet long-established.

If the wholesaler deals in spare parts, naturally he has no power on the price that the manufacturing firm will supply him at, except if he is a very big dealer in such spare parts and stocks parts of products of other producers (e.g. spare parts of cars). Thus the demand of wholesalers for the product of a manufacturing firm will have in most cases a negative slope.

Retailers:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Here also we must distinguish between two types of action of the retailer: he may resell the manufactured product branded, or he may sell it under his own brand name. Large supermarkets sell an increasing number of products with their own brand name (Spar, St Michael, Co-op, Tesco), but they also sell other brands. They can influence to a certain degree the final consumer by not stocking a particular brand.

The effectiveness of such policy depends on whether they have a locational monopoly, and in any case their discretion can only be important in the short run. The locational advantage can easily be lost, by a new retailer establishing a new shop close to them. Furthermore, retailers are interested in their profit margin, and there is no reason why they should not pay a higher price for a certain branded commodity if they can pass it on to the consumers who have a preference (rational or irrational) for this particular brand.

It is only if they buy goods to resell under their own brand name that they will not be prepared to pay a higher price for a ‘raw material’ they can obtain cheaper from another supplier. In summary, if the retailer buys a commodity already branded in order to resell it, his demand (from the manufacturer of the branded product) will be downward sloping, reflecting the preferences of the final consumers; if, however, he buys the commodity as a ‘raw material,’ to resell it under his own brand name, then his demand will be infinitely elastic.

The conclusion of the above discussion is that the shape of the demand curve of an oligopolistic will depend on the nature of his product and his distribution channels. The demand function of the oligopolistic is multivariate. Thus even if prices are sticky, there are other factors that influence the demand to the firm. In principle, the demand for the product of a firm can be estimated statistically from historical observations of sales, prices charged by the firm and its competitors, advertising expenditures, and other relevant factors.

However, the difficulties involved in this process are so great that very few firms attempt to estimate statistically their own demand function. Even if the estimation difficulties are overcome, the environment of the firm in the real world changes so fast that any statistical (historical) demand function becomes inappropriate for future decision unless continuously revised. Given the uncertainties of the environment (and the scarcity of good econometricians), firms tend to avoid price competition and to rely on other competitive weapons.

The predominance of non-price competition in the modern highly competitive oligopolistic world suggests that the demand curve is often a subjective concept in the decision-making process of businessmen: because they are uncertain about the effects of price changes, businessmen prefer to use other instruments, such as style of the product, advertising, research and development programmes, which they consider as less dangerous.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Their market share at the given price will be determined by the effectiveness of such policies, as well as by the dynamic changes in the market conditions. In oligopolistic markets the determinants of the market share (at the given price) are the determinants of the demand function of the firm, and their effect is shown graphically by shifts of the (subjective) demand curve at the going price (figure 2.47). If sales, and hence market-share, change at a given price one must look at the other determinants of demand in order to explain the change.