The below mentioned article provides an overview on the theory of full-cost or average cost pricing.

In 1939, Hall and Hitch of the University of Oxford mounted a ‘root-and-branch’ attack on the notion of profit maximisation on the basis of answers to questionnaires of 38 entrepreneurs, 33 of whom were manufacturers, 3 retailers and 2 builders.

Hall and Hitch sought information from them about the elasticity and the position of their demand, and their attempts to equate their estimated marginal cost and marginal revenue. The answers revealed that the majority of them apparently made no efforts, even implicitly, to estimate elasticities of demand or marginal cost. They did not consider them to be of any relevance to the pricing process.

On the basis of the empirical study, Hall and Hitch concluded that the majority of entrepreneurs under oligopoly base their selling prices upon, what they call, ‘full cost’ and including an allowance of profit, and not in terms of the equality of marginal cost and marginal revenue at all.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus a price based on full average cost is the ‘right price’, the one which ‘ought to be charged’, based on the idea of ‘fairness to competition’ under oligopoly. But what is full cost? Full cost is full average cost which includes average direct costs (AVC) plus average overhead costs (AFC) plus a normal margin for profit: Thus price, P = AVC + AFC + profit margin (usually 10%).

According to Hall and Hitch, there are certain reasons which induce firms to follow the full-cost pricing policy:

(i) Tacit or open collusion among producers;

(ii) Failure to know consumers’ preferences;

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) Reaction of competitors to a change in price;

(iv) Moral conviction of fairness; and

(v) Uncertainty of effects of price increases or decreases. All these reasons prevent oligopolistic producers from setting a price other than the full-cost price.

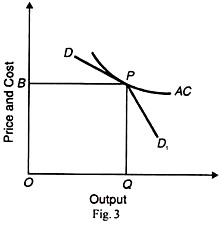

Thus firms set their price on the basis of the full-cost principle and sell at that price whatever the market takes. They observed that prices were sticky in the oligopoly market despite changes in demand and costs. They explained the stickiness of prices in terms of the kinked demand curve. The kink occurs at the point where the price QP (= OB) fixed on the full-cost principle actually stands in Figure 3.

Any increase in the price above it, will reduce the firm’s sales, for its competitors will not follow it in raising their prices. This is because the PD portion of the kinked demand curve is elastic. On the other hand, if the firm reduces the price below QP, its competitors will also reduce their prices.

The firm will increase its sales but its profits will be less than before. This is because the PD1 portion of the curve is less elastic. Thus in both the price-raising and price-reducing situations, the firm will be a loser. It would, therefore, stick to the price QP so long as the prices of the direct factors of production (i.e., raw materials, etc.) remain unchanged.

As the AC curve falls over a large range of output, price varies inversely with output. The smaller the level of output, the higher will be the average cost and the higher the price of the product. But Hall and Hitch rule out the possibility of oligopoly firms producing small outputs and charging higher prices.

They give three reasons for this;

(a) Oligopoly firms prefer price rigidity,

(b) They cannot raise the price because of the kink, and

(c) They want to “keep the plant running as full as possible, giving rise to a general feeling in favour of price concessions”.

Hall and Hitch mention two exceptions to this phenomenon of a rigid price:

(i) If the demand decreases much and remains so for some time, the price is likely to be reduced in the hope of maintaining output. This is likely to happen when the lower portion of the demand curve becomes more elastic. The reason for this price- cut is when one firm becomes panicky and reduces its price; it forces others to cut their prices,

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Any circumstances which lower or raise the AC curves of all firms by similar amounts due to changes in factor prices or technology are likely to lead to a revaluation of the full-cost price QP (= OB). But there is no tendency for prices to fall or rise more than the wage and raw material costs.

The Andrews Version:

The Hall-Hitch explanation is based on the presumption that the price to be charged in the oligopoly market is pre-set by the firm. Further, the kinky demand curve complicates the analysis. In order to simplify the exposition, we give a modified version of the full-cost pricing by Prof. Andrews.

Prof. Andrews in his study Manufacturing Business, 1949, explains how a manufacturing firm actually fixes the selling price of its product on the basis of the full cost or average cost. The firm finds out the average direct costs (AVC) by dividing the current total costs by current total output. These are the average variable costs which are assumed to be constant over a wide range of output.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In other words, the AVC curve is a straight line parallel to the output axis over a part of its length if the prices of direct cost factors are given. The price which a firm will normally quote for a particular product will equal the estimated average direct costs of production plus a costing-margin or mark-up.

The costing-margin will normally tend to cover the costs of the indirect factors of production (inputs) and provide a normal level of net profit, looking at the industry as a whole.

The usual formula for costing-margin (or mark-up) is,

M = P-AVC/AVC ……..(1)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Where M is mark-up, P is price and AVC is the average variable cost and the numerator P-AVC is the profit margin. If the cost of a book is Rs. 100 and its price is Rs. 125,

M = 125-100/100 = 0.25 or 25%

If we solve equation (1) for price, the result is

P = AVC (1 + M) ……. (2)

The firm should set the price

P = Rs. 100 (1 + 0.25) = Rs. 125.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Once this price is chosen by the firm, the costing-margin will remain constant given its organisation, whatever the level of its output. But it will tend to change with any general permanent changes in the prices of the indirect factors of production.

Depending upon the firm’s capacity and given the prices of the direct factors of production (i.e., wages and raw materials), price will tend to remain unchanged, whatever the level of output. At that price, the firm will have a more or less clearly defined market and will sell the amount which its customers demand from it.

But how is the level of output determined?

It is determined in any of the three ways:

(a) As a percentage of capacity output; or

(b) As the output sold in the preceding production period; or

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) As the minimum or average output that the firm expects to sell in the future.

If the firm is a new one, or if it is an existing firm introducing a new product, then only the first and third of these interpretations will be relevant. In these circumstances, indeed, it is likely that the first will coincide roughly with the third, for the capacity of the plant will depend on expected future sales.

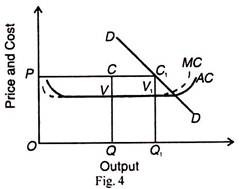

The Andrews version of full-cost pricing is illustrated in Figure 4 where AC is the average variable or direct costs curve which is shown as a horizontal straight line over a wide range of output. MC is its corresponding marginal cost curve.

Suppose the firm chooses OQ level of output. At this level of output, QС is the full-cost of the firm made up of average direct costs QV plus the costing-margin VC. Its selling price OP will, therefore, equal QC.

The firm will continue to charge the same price OP but it might sell fig. 4 more depending upon the demand for its product, as represented by the curve DD. In this situation, it will sell OQ1 output. This price will not be altered in response to changes in demand, but only in response to changes in the prices of the direct and indirect factors.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Criticism:

The full-cost pricing theory has been severely criticised on the following grounds:

(1) Not free from profit maximisation:

Critics like Robinson and Kahn have pointed out that the full-cost pricing theory is not free from the elements of profits maximisation which entered into the pricing decisions of many of the firms investigated by Hall and Hitch.

(2) Whose full cost?

One of the weaknesses of the theory is that it fails to point out the firm whose full cost will determine the price in the oligopoly market that will be followed by the other firms.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(3) Firms follow Independent price policy:

The full-cost pricing theory is criticised for its adherence to a rigid price. Firms often lower the price to clear their stocks during a recession. They also raise the price when costs rise during a boom. Therefore, firms often follow an independent price policy rather than a rigid price policy.

(4) Circular relationship:

If fixed costs of a firm form a large proportion of its total cost, a circular relationship may arise in which the price would rise in a falling market and fall in an expanding market. This happens because average fixed cost per unit of output is low when output is large, and when it is small, average fixed cost per unit of output is low.

(5) Profit margin a vague concept:

Moreover, the term ‘profit margin’ or ‘costing margin’ is vague. The theory does not clarify how this costing margin is determined and charged in the full cost by a firm. The firm may charge more or less as the just profit margin depending on its cost and demand conditions.

As pointed out by Hawkins, “The bulk of the evidence suggests that the size of the ‘plus’ margin varies: it grows in boom times and it varies with elasticity of demand and barriers to entry.”

(6) Naive method:

This pricing method is naive because it does not explicitly take into account the elasticity of demand. In fact, where the price elasticity of demand for a product is low, the cost plus price may be too low, and vice versa.

(7) Not for perishable goods:

This method cannot be used for price determination of perishable goods because it relates to the long period.

(8) Full-cost pricing principle not strictly followed:

Empirical studies in England and the U.S. on the pricing process of industries reveal that the exact methods followed by firms do not adhere strictly to the full- cost principle. The calculation of both of average cost and the margin is a much less mechanical process than is usually thought.

As a matter of fact, businessmen are reluctant to tell economists how they calculated prices and to discuss their relations with rival firms so as not to endanger their long-run profits or to avoid government intervention and maintain good public image.

(9) Firms follow marginal principles;

Prof. Earley’s study of the 110 ‘excellently managed companies in the U.S. does not support the principle of full-cost pricing. Earley found a widespread distrust of full-cost principle among these firms. He reported that the firms followed marginal accounting and costing principles, and the majority of them followed pricing, marketing and new product policies.