New Economics or Keynesian Revolution:

We will discuss the other branch of Economics, viz., macro economics or the analysis of the economy as a whole.

This is also called the theory of income determination or the theory of employment.

We discuss here how the aggregate income of an economy is determined and what causes fluctuations in the level of the economy’s aggregate income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Given the amount of capital, technology and quality of labour, a country’s national income, i.e., the total output of goods and services, can be increased by increasing employment. Therefore, the larger the national income of a country the larger the volume of employment; and the smaller the national income, the smaller the volume of employment. Thus, in the short run, the factors that would determine the economy’s level of national income would also determine its level of employment. Hence, the theory of income determination is also called the theory of employment.

The credit for expounding a theory of income and employment goes to J M. Keynes, an English economist (1884-1946). In 1936, he published his epoch-making book General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money and set out his new theory in it. Prior to it, economists confined their attention to what we now call ‘price theory’ and did not analyse the economy as a whole. In fact, the earlier economists believed that normally there was full employment in the economy and, therefore, the level of national income normally corresponded to the level of full employment.

Our observation of economic life, however, is quite different. The Great Depression of the early nineteen thirties was an eye-opener. There was then widespread and acute unemployment and a sharp fall in national incomes throughout the world. Obviously, there was something seriously wrong with the above belief of the earlier economists. Keynes not only proved that they were wrong but also formulated a comprehensive theory to explain how the level of income and employment in an economy is determined.

In the light of his theory, he also indicated what economic policies be adopted to attain and maintain full employment and thus to raise the level of national income. Keynes thus gave a new turn to Economics this is why his theory and ideas have been given the name of New Economics, and some people go to the extent of calling it Keynesian Revolution. In an elementary book as this one, it is not proposed to attempt a detailed account of the Keynesian theory of income determination; only a preliminary idea would be given and that also only in outline.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Principle of Effective Demand:

Keynes’s theory of income and employment is based on the Principle of Effective Demand. However, in order to be able to understand this principle, it is necessary first to know the concepts of Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand. It should not be difficult to see that, in the individual firm, employment will depend on the entrepreneur’s ideas about how many men he must employ to maximise profits.

Similarly, in the economy as a whole, employment will depend on the decision of all individual employers, added together, about how many men to employ in order to maximise profits. The main factors which determine the level of employment in the economy as a whole, according to Keynes, are Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand.

Aggregate Supply:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In an economy, all entrepreneurs, taken together, employ a certain total number of labour, who in turn produce a certain quantity of output. The total cost of producing the output by that number of men is called the ‘aggregate supply price.’ It is easily understandable that unless entrepreneurs as a whole expect to cover their costs (aggregate supply price) when they employ, say X men, they will not consider it worth-while employing so much labour, and employment will be reduced.

On the other hand, if they expect to receive more than their costs (aggregate supply price), they will wish to employ more men and employment will then be increased. “At any given level of employment of labour, aggregate supply price is therefore the total amount of money which all the entrepreneurs in the economy, taken together, must expect to receive from the sale of the output produced by that given number of men, if it is to be just worth employing them.”

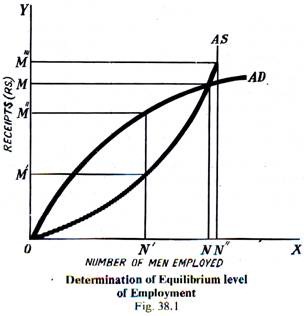

In this way, corresponding to each possible level of employment in the economy, there will be a different aggregate supply price. We can thus construct for the economy an aggregate supply price schedule and also draw an aggregate supply price curve (see curve AS in Fig. 38.1).

Aggregate Demand:

Now let us take the demand side. When a certain number of labour is employed by all the entrepreneurs, taken together, and a certain quantity of output is produced by them and is sold, it fetches a certain amount of money. How much it will fetch will depend on the state of demand in the economy. The expected receipts of entrepreneurs by the sale of total output when a given volume of employment is offered to workers is called the Aggregate Demand Price.

In other words, the “aggregate demand price at any level of employment is the amount of money which all the entrepreneurs in the economy taken, together really do expect that they will receive if they sell the output produced by this given number of labour.”

In the definitions of Aggregate Supply Price (AS) given in the preceding section and that of Aggregate Demand Price (AD) given in this section, the words “must expect to receive” and “do really expect that they will receive” occur. The distinction between the two must be clearly understood.

In AS the entrepreneurs must recover their cost, otherwise they will not employ that number of men. In AD, however, the idea is that the demand is such that the entrepreneurs do expect to receive that amount of money by the sale of goods produced by that number of men.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Like the aggregate supply price, there will be a different aggregate demand price for different levels of employment in the economy. We can thus construct for the economy an aggregate demand price schedule and also draw an aggregate demand price curve (see curve AD in Fig. 38.1).

Determination of the Equilibrium Level of Employment:

In Figure 38.1, aggregate demand curve (AD) and aggregate supply curve (AS) have been drawn. Along the X-axis are measured the number of men employed, and along the Y-axis are shown the various amounts of receipts received by all entrepreneurs in the economy, taken together, from the sale of output. To put it alternatively, these receipts of the entrepreneurs are the different levels of expenditure incurred by the community on purchasing the entrepreneurs’ output.

Let us take the AS curve first. It shows, for each possible volume of receipts by entrepreneurs from the sale of output, how many men it would be just worth employing. For example, if entrepreneurs expected to receive Rs. OM’, it would just pay them to employ ON’ men. Now look at AD curve.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This shows how much money the community would actually spend on the outputs produced by the different volumes of employment, i.e., how much money entrepreneurs really do expect to receive when they employ various numbers of men. For example, if ON’ men are employed, entrepreneurs would expect to receive Rs. OM from selling the output produced.

It is noteworthy about AS curve that it rises slowly to begin with. It implies that as the number of men employed increases, cost of output does not rise rapidly. If the amounts received by entrepreneurs continued to rise, employment would rise progressively less sharply until all those who wanted jobs are employed. In Fig. 38.1, there are ON” men wanting jobs, and if entrepreneurs’ receipts had risen to Rs. OM ” ‘, it would be worth employing all of them.

But even if the receipts of entrepreneurs (expenditure of the community) were to rise above Rs. OM” ‘, employment would not increase any further, because all persons seeking employment have secured employment. At this point (i.e., point on AS curve corresponding to ON”), the elasticity of supply of labour falls to zero and now AS curve rises vertically.

Now observe the shape of the AD curve. It rises quite steeply as employment first rises, but the rapidity of this rise tends to slacken when employment reaches high levels. Why this is so should be very easy to understand. At low levels of employment, people’s income is low and they would consume most of it and save very little; but as employment reaches high levels, the people’s income rises and they now save much more, and thus their expenditure on goods and services does not increase proportionately.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now what would be the volume of employment which the entrepreneurs would actually offer at any time in an economy? From the above explanation of AS and AD curves, it should not be difficult to understand that aggregate demand (i.e., AD curve) and aggregate supply (AS curve) between them determine the volume of employment which actually is offered by entrepreneurs.

If aggregate demand (AD) is higher than aggregate supply (AS), as is the case at any point to the left of ON. it means that by employing a larger number of men, entrepreneurs would be able to get a larger sum of money from the sale of output than they would have to spend on producing that output. Entrepreneurs would in such circumstances like to employ more men till ON men, in all, are employed and aggregate supply equals aggregate demand. (AS = AD at the point corresponding to employment of ON men.)

On the other hand, if employment exceeds ON, aggregate demand curve now lies below aggregate supply curve. In other words, beyond ON, entrepreneurs expect to receive less at each level of employment than the minimum amount of money required to make that amount of employment worth offering and they would be incurring losses if they were to employ more than ON men. The decisions of individual entrepreneurs will thus lower employment to ON, since they will all wish to avoid losses and will reduce employment to do so.

We have thus seen that the level of employment in an economy will be determined by the intersection of the aggregate demand curve and the aggregate supply curve. The economy as a whole will be in equilibrium only when the amount of money which entrepreneurs expect to receive from providing any given number of jobs (AD) is just equal to the amount which they must receive (AS). This is the only possible equilibrium position, given the AS and AD curves, assuming that there is perfect competition.

Effective Demand:

We are now in a position to understand the principle of effective demand. We owe the concept of ‘effective demand’ to the late Lord Keynes. It is quite different from the term ‘aggregate demand’ as used by Keynes. We have seen that the aggregate demand of an economy is different at different levels of employment or, in other words, we can construct an aggregate demand schedule for the economy. But at which aggregate demand will the economy be in equilibrium?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As we have seen in the preceding section, the economy is in equilibrium at that level of employment at which the aggregate demand curve intersects the aggregate supply curve or at which aggregate demand in the economy is equal to aggregate supply. That aggregate demand at which the economy is in equilibrium is called Effective Demand.

Thus, “Effective Demand is that aggregate demand price which becomes effective, because it is equal to aggregate supply price and thus represents a position of ‘short-run’ equilibrium.” It is distinguished in this way from all other points on the aggregate demand schedule. It represents an equilibrium position which actually is realized, while at all other point’s aggregate demand is either greater or less than aggregate supply.

Equilibrium at Less Than Full Employment:

A very important point about ‘effective demand’ is that owing to certain causes, it may be deficient so that the economy can be in short-run equilibrium and yet there may be considerable unemployment.While the full employment level is ON”, effective demand or the equilibrium level of employment is at ON, when NN” number of men are still unemployed. Keynes greatly emphasised this point and, in this way, was able satisfactorily to explain the existence of prolonged unemployment.

On the other hand, the earlier economists (classical) had wrongly assumed that the aggregate demand was always large enough to equal the aggregate supply price corresponding to full employment. With the help of his principle of effective demand, Keynes was able to show that the above assumption of the classical economists was wrong and that the economy could be in equilibrium and yet suffer from substantial volume of unemployment.

The above analysis has a great practical importance. It suggests the right method of removing unemployment, viz., the Government taking suitable steps to raise effective demand to the level of aggregate supply which corresponds to full employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Outline of Keynes’s Theory of Income and Employment:

We have seen above that in any economy effective demand represents the amount of money actually being spent on the entire output of the economy. In other words, effective demand represents the value of the national output and since national output consists of two types of goods—consumption goods and investment goods—the value of national output is equal to the demand for or expenditure on consumption goods plus demand for or expenditure on investment goods.

But it is easy to see that in an economy, one man’s expenditure is some other people’s income. We can, therefore, look upon effective demand also as the income or receipts of all the factors of production, since all the money which entrepreneurs receive must be paid out in the form of wages, rent, interest and profit. Effective Demand thus equals the national income, i.e., the incomes or receipts of all members of the-community.

We can therefore sum up as under:

Effective Demand = National Income

=Value of National Output = Expenditure on Consumption Goods + Expenditure on Investment Goods.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

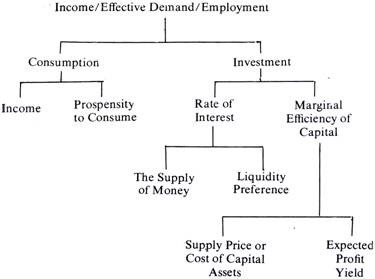

Now this should give some indication of Keynes’s theory of income and employment. We have seen that income and employment depend upon effective demand and effective demand depends on consumption demand plus investment demand.

Keynes therefore proceeded to analyse in detail the factors on which consumption and investment demands depended and in doing so developed certain other new concepts, viz., propensity to consume, investment multiplier, marginal efficiency of capital and liquidity preference. It may take us too far to explain all these Keynesian concepts.

We shall therefore content ourselves with presenting the Keynesian theory of income and employment in a summary form in terms of the following propositions:

(i) In an economy, in the short run, its total income depends on the volume of employment.

(ii) Total employment depends on total effective demand and, in equilibrium; aggregate demand is equal to aggregate supply.

(iii) Aggregate supply depends on physical and technical conditions of production and, in the short run, these do not often change. Hence it is changes in aggregate demand that bring about changes in income and employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iv) Effective demand is made up of (a) consumption demand, and (b) investment demand.

(v) Consumption demand depends on propensity to consume. In the short run, propensity to consume is relatively stable.

(vi) Propensity to consume being relatively stable, investment demand or investment expenditure has a crucial role in determining the level of employment.

(vii) Investment demand depends on (a) the marginal efficiency of capital, and (b) the rate of interest. Since the rate of interest is relatively stable, marginal efficiency of capital is of crucial importance.

(viii) The marginal efficiency of capital depends on (a) the businessmen’s expectations of profit yields, and (b) the replacement cost of capital assets.

(ix) The rate of interest depends on: (a) the quantity of money, and (b) the state of liquidity preference.

(x) In the short run, the rate of interest is relatively stable; therefore the marginal efficiency of capital is by far the more important determinant of investment, which, as pointed out above, plays a strategic role in determining the level of income and employment in an economy.

Keynesian Theory in a Chart:

The Keynesian theory outlined above can also be presented in the form of a chart as under: