The classical theory of rent is associated with the name of David Ricardo. He begins with a group of new settlers in a new country.

Let us suppose ourselves to be the settlers in a hitherto unknown island which we shall call jawahar Island after our late beloved leader.

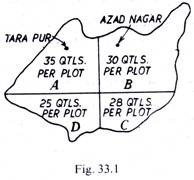

As we study the natural resources of Jawahar Island, we find the land to be of four grades. For convenience, we call them A, B, C and D in the order of their fertility. We shall settle down in Tarapur in ‘A’ part of the island (See Fig. 33.1).

This is the most fertile land and gives us the largest produce per acre. Enough land is available of this quality to satisfy all our needs at the moment. Therefore, it is u free good and will not command any price, i.e., rent. But as time passes, the mouths to be fed increase in number. This may be due to more immigrants, who have heard of our good luck, or due to an increase in population.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Rent in Extensive Cultivation:

A time comes when all land of the best quality has been taken up. But some demand still remains unsatisfied. We have then to resort to ‘B’ quality land. It is inferior to ‘A’ and yields only 30 quintals of wheat per plot as compared with 35 quintals of ‘A’ with the same expenditure of labour and capital. Naturally plots in ‘A’ now acquire a greater value as compared with ‘B’. A tenant will be prepared to pay up to 5 quintals of wheat in order to get a plot in the ‘A’ zone, or take ‘B’ quality land free of charge.

This difference, paid to the owner (if the cultivator is a tenant) or kept to himself (if he is the owner), is economic rent. In the first case (i.e., when the cultivator is a tenant) it is contractual rent; and in the latter (i.e., when the cultivator is the owner) it is known as implicit rent. ‘B’ plots do not pay any rent. To go a step further, we see that after all land of ‘B’ quality has also been taken up, we begin cultivating ‘C’ plots. Now even ‘B’ quality land comes to have differential surplus over ‘C’. Rent of ‘A’ increases still further.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

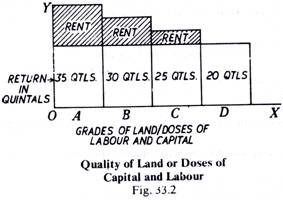

When the demand increases still more, we are pushed to the use of the worst land, which is of ‘D’ quality yielding 25 quintals per plot. ‘D’ quality land is now no-rent land or marginal land while ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C all earn rent. This growing demand shows itself in rising prices. They raise high enough to cover the expenses of cultivation on the lowest grade land, i.e., ‘D’ quality.

Let us suppose that one unit of productive effort is equal to Rs. 3,500. When only A’ quality land, where a plot produces 35 quintals is under the plough, the price of wheat will be Rs. 100 per quintal. When owing to increased demand, the price of wheat rises to Rs.-110 then and only then will ‘B’ quality land be cultivated which produces 30 quintals of wheat. And when that happens ‘A’ land will have a surplus of 5 quintals X Rs. 110 = Rs. 550 per plot. This becomes rent.

The difference, in other words, between the return from a plot of land above the margin and the marginal plot (i.e., the one just paying its way) is called rent or economic rent.

Rent in Intensive Cultivation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The settlers in Jawahar Island realize that there is another way too of increasing the produce. Why not apply more labour and capital to superior lands, and resort to intensive cultivation? This is done but it is seen that the law of diminishing returns sets in. Look at Fig. 33.1 again. Now consider that A, B, C and D are the different doses of labour and capital (instead of different grades of land) applied to the same grade of land. The first dose yields 35 quintals.

The second unit of labour and capital used on ‘A’ plot will almost definitely give us less than the first. We suppose it gives us only 30 quintals. So we have the choice of either taking new plots in ‘B’ land, or cultivating ‘A’ lands more intensively. If we adopt the latter course, the first unit of labour and capital will be yielding a surplus over the second unit—which unit produces just enough to cover the expenses. This surplus, again, is rent. As more and more units of labour and capital are applied, the return per unit will go on falling.

Rent Due to Differential Advantages:

With the passage of time, however, a new factor emerges. A locality in the A’ zone—marked Tarapur in Fig. 33.1—develops into a market and Azadnagar in ‘B’ into a railway junction, and produce has to be sent to those two flourishing localities for their final disposal. Now the plots situated in the neighbourhood of Tarapur and Azadnagar come to have an advantage. They have either no transport charges or much smaller charges than in the case of lands in ‘C’ and D’ areas.

Transport charges are a part of the cost of production, because production is complete only when the commodity reaches the hands of consumers. The better-situated plots, which have to bear less transport charges, will enjoy a surplus over the distant ones. This surplus will be another cause of rent. Hence, economic rent is a surplus which arises on account of natural differential advantages, whether of fertility or of situation, possessed by the land in question over the marginal land.

No-rent or Marginal Land:

The cases described above show that rent is earned due to a certain paces being better suited for cultivation or being better situated in regard to markets. But better than what? Of course better than some other plot of land. This ‘some other’ plot is marginal land which just covers its expenses and no more. This land is called ‘no-rent land’. All rents are measured from it upwards.

In fig. 33.2 ‘D’ quality and land which produces 20 quintals per plot is the marginal land. Here the return and cost are equal. It is just worthwhile cultivating this land, since it just covers expenses of cultivation and yields no surplus to the cultivator.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is quite possible that we may not be able to spot the ‘no-rent land’ because:

(a) It may be paying scarcity rent, or

(b) The owner might have invested some capital in it and the interest thereon might be mistaken for rent, or

(c) The no-rent land may be in some other country or

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(d) The no-rent tracts may form part of a rent-paying area and be concealed in it.

Scarcity Rent:

In our new home-country, Jawahar Island, we at last come to a situation when all the lands have been brought under the plough, and are being cultivated intensively too. But the price rises still further under the pressure of demand. Population has been increasing fast. Our country has become old and no more land is available as we are an island country. Prices of agricultural produce go up and, therefore, incomes from land go up.

Hence, all land (including the no-rent ‘D’ quality land) begins to get surplus above expenses. This surplus above costs in the ‘D’ quality land, our previous no-rent land, is scarcity rent. Superior lands will be paying this surplus over and above differential gain.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Conclusion:

Summing up, we can say that, according to the Ricardian theory, rent is a differential surplus and arises from the fact that land possesses certain peculiarities as a factor of production. It is limited in area and its fertility varies. Besides, its situation is fixed.

Thus rent results because:

(a) Fertility is more or less fixed by nature;

(b) The total stock of land is fixed and cannot be increased.

On this basis, Ricardo defines rent as “that portion of the produce of the earth which is paid to the landlord for the original and indestructible powers of the soil.” According to him fertility, situation and limited total stock—these qualities, which are original as well as permanent, give, rise to rent.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Criticism of Ricardian Theory:

The Ricardian theory of rent has been widely criticised as under:

(i) It is pointed out that fertility of land is not original:

Much of the present productive capacity of land is the result of human efforts, use of manures and other improvements. Thus, it is not possible to say which qualities of land are original and which of them are man’s creation.

Situation is something which man cannot change. Obviously it is not possible to move a plot of land to another place. But man can improve the means of transport so much that the distance between two places matters little Thus he can manage to change the character of a place. The planned cities and factory towns of today are the product of man’s brain. Although this criticism has a leg to stand upon, it cannot be denied that certain original qualities do matter. No human effort will change Rajasthan into Kashmir.

(ii) The idea of indestructibility is objected to:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Area, it is said, is everlasting but not fertility. Continued cultivation exhausts fertility. We observe this in the case of land in India. Lands are reported to be less fertile and, therefore, less productive per hectare today than they were in the past.

Ricardo’s doctrine, however, cannot be wholly rejected. Land which is naturally fertile regains its fertile qualities more easily, if it is manures or left fallow. Creation of fertility in a barren land is more difficult. Besides no amount of use will entirely kill the fertility of land.

(iii) Certain American economists like Carey have criticised the classical theory of rent on historical grounds. They say that cultivation did not begin with the most fertile lands when the first settlers arrived in America, nor did it pass on to the less fertile lands in that order. The reason was that some of the most fertile lands were covered with thick forests while others were open to enemy attack. The settlers naturally preferred less fertile areas which were open and could be defended.

This criticism answers itself. Not necessarily the most fertile, but the land offering the best reward for a definite effort is occupied first. Moreover, the order of cultivation is not so important. Even if the order is changed, when two types of land are being cultivated, the more fertile or better situated plot will produce a surplus above the cost.

The surplus will arise whichever land is cultivated before the other. Rent will still arise even if all the lands were of uniform quality. It will arise in the intensive form.

(iv) It is said that rent is not due to differential advantages only. Even if all lands were of uniform quality, rent would still arise. Rent arises from scarcity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(v) Ricardian theory does not say why rent is paid; it only tells us that superior lands command higher rent.

(vi) The concept of marginal land is said to be imaginary, theoretical and not realistic.

(vii) It is also urged that no special theory of rent is necessary. Demand and supply theory, which explains all values, can explain rent also.

(viii) Modern economists think that it is only from the point of view of economy as a whole that land has perfectly inelastic supply and earns a surplus or rent. This surplus is not included in cost and hence does not enter into price. But from the point of view of individual farmer or industry, a payment has to be made to prevent land from being transferred to some other use.

The payment, called transfer earnings, is an element of cost and hence enters into price. For the individual farmer the whole of rent is cost. “This concept of transfer earnings helps to bring the simple Ricardian Theory—where transfer earnings are zero because it is the whole economy which is being studied—into a closer relation with reality.”— (Stonier and Hague).

Rent as Payment for the Use of Land: Modern View:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So far as the use of land is concerned, the modern economists have offered a better explanation of rent. This payment is obviously determined by the demand for and the supply of land.

Demand Side:

The demand for land is a derived demand. It is derived from the demand for the products of land. If the demand for these products rises or falls, the demand for the use of land will correspondingly rise or fall leading to increase or decrease of rents. For instance, if the population of a country increases, the demand for food will increase, resulting in increased demand for land and rise m its rent, and vice versa.

The demandfor a factor of production depends on its marginal revenue productivity (or in short, marginal productivity). This productivity is subject to the law of diminishing marginal productivity. That is why, as in the case of other factors, the demand curve DD shown in the following figures slopes down from the left to the right. Thus, on the side of demand, rent of land is determined by its productivity, not total productivity, but marginal productivity.

Supply Side:

The supply of land is fixed so far as the community is concerned, although individuals can increase their own supply by acquiring more land from others or decrease its supply by parting with land. In spite of reclamation projects, the effect of which on the total supply is negligible, the supply of land remains practically fixed.

It is a case of perfectly inelastic supply, which means that whatever the rent (the rent may rise or fall), the supply remains the same. That is why it is said that land has no supply price. In other words, the supply of land in general is absolutely inelastic and as such its supply is independent of what it earns.

Interaction of Demand and Supply:

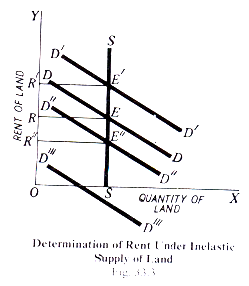

We have analysed the demand and the supply sides of land. The interaction of these forces is shown in Fig. 33.3. We assume that land is homogeneous and it is used for raising one crop only. Then there can be one demand curve and one supply curve. We also assume perfect competition. SS supply curve, a vertical straight line, represents fixed supply. We start with DD as the total demand curve for land. These two curves intersect at E.

In this position OR (=SE) is the rent. If rent is less (i.e., OR) the demand for land will increase; but the supply is fixed, hence rent will again rise to OR. Suppose rent rises above OR (i.e., to OR’), then the demand for land will decrease and bring the rent back to OR.

Suppose now that, on account of increase in population or otherwise, the demand for land has increased from DD to D’D’. The supply curve is still the same SS. The new point of intersection will be E’ and therefore the rent will be OR’. If demand falls to D”D”, the demand and supply curves intersect at E”, and the rent will be OR”. If the country is entirely new and land of good quality is surplus, then there will be no rent. The condition is shown by D’ “D”.

If the land is of different qualities, then each quality will have a separate demand curve and they will command different rents. Hence the theory explains differential rent too. Thus, the rent of land, like the remuneration of other factors, is determined by the equilibrium between demand for and supply of land.

In other words, it is scarcity in relation to demand that determines rent. Fundamentally speaking, rent is paid for land because the produce of land is scarce in relation to its demand. The scarcity of land is in fact derived from the scarcity of its products. It is this scarcity which explains all values and rent is no exception.

Land for a Particular Use:

We have analysed above total demand and total supply of land for the community as a whole. Let us now consider it from the point of view of a particular industry or use. For a particular use or industry, the supply of land cannot be regarded as fixed. By offering more rent, it can be increased; the supply will decrease if the rent in this particular case goes down.

The supply is thus elastic and the supply curve will rise upwards from left to right, as is shown in Fig. 33.4. DD is the demand curve to start with. E is the point of intersection, hence OR (= EM) is the rent and OM is the land used.

Suppose demand increases to D’D’. Now the two curve? Intersect at E’ and the rent will be OR’ and the land used OM’. This means that since for this particular use, the rent of land has gone up, MM’ land has been withdrawn from other uses and put to this use. Similarly, if demand decreases to D”D”, the rent will come down to OR” and the quantity of land used to OM”, which means MM” land has gone out of this particular use, sine: the rent has fallen.