The second point that needs emphasis here is that aside from retaliation, the shape of the foreign country’s offer curve will largely determine the degree to which a country will improve its terms of trade by imposing a tariff.

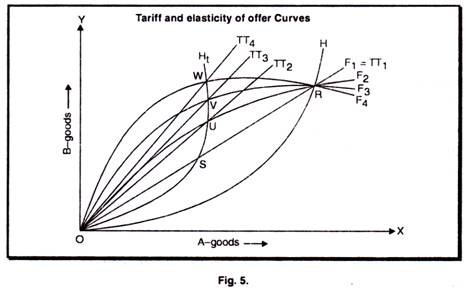

In the following figure 5, there are a number of foreign offer curves of different elasticities OF1, OF2, OF 3 and OF4. The home country imposes a tariff that shifts its offer curve from OH to OHt.

If the foreign offer curve is completely elastic (OF1), it must be identical to the free trade terms of trade line.

A perfectly elastic offer curve means that a country is willing to offer its exports in return for imports of a certain fixed ratio of exchange, which never changes no matter how much it imports or exports. In this case it is impossible for the home country to change its terms of trade no matter what it does to its tariffs. The terms of trade at (s) are the same as they were at (R).

The less elastic the foreign country’s offer curve, the more a given tariff change will improve the home country’s terms of trade (assuming no retaliation). The same tariff induced shift in the home country’s offer curve (OH-OH1) produces equilibrium (S, U, V, W) which show increasingly favourable terms of trade (TT1 , TT2 , TT3, TT4), the less elastic the offer curve of the trading partner.

Here again we can talk in terms of “small” versus “big” countries. For all intent and purposes, the offer curve of the rest of world facing Guatemala, Upper Volta, and so on are perfectly elastic since these small countries are economically insignificant relative to their trading partner, the rest of the world.

They possess no monopoly or monopsony power at all. Hence, they are unable to affect their terms of trade by their own actions; the terms of trade are dictated to them. This raises certain questions in connection with trade and economic development which is of considerable interest.