Let us learn about Business or Trade Cycle. After reading this article you will learn about: 1. Meaning of Business Cycles 2. Characteristics of Business Cycles 3. Phases of a Business Cycle 4. Theories 5. Control.

Meaning of Business Cycles:

A capitalistic economy experiences fluctuations in the level of economic activity. And fluctuations in economic activity mean fluctuations in macroeconomic variables. At times, consumption, investment, employment, output, etc., rise and, at other times, these macroeconomic variables fall. Such fluctuations in macroeconomic variables are known as business cycles.

A capitalistic economy exhibits alternating periods of prosperity or boom, and depression. Such movements are similar to wavelike movements or seesaw movements. Thus, the cyclical fluctuations are rather regular and steady but not random. Since GNP is the comprehensive measure of the overall economic activity, we refer to business cycles as the short term cyclical movements in GNP.

In the words of Keynes:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

“A trade cycle is composed of periods of good trade characterized by rising prices and low unemployment percentages, alternating with periods of bad trade characterized by falling prices and high unemployment percentages.”

In brief, a business cycle is the periodic but irregular up-and-down movement in economic activity. Since their timing changes rather unpredictably, business cycles are not regular or repeating cycles like the phases of the moon.

Characteristics of Business Cycles:

Following are the main features of trade cycles:

i. Industrialized capitalistic economies witness cyclical movements in economic activities. A socialist economy is free from such disturbances.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. It exhibits a wavelike movement having a regularity and recognized patterns. That is to say, it is repetitive in character.

iii. Almost all sectors of the economy are affected by the cyclical movements. Most of the sectors move together in the same direction. During prosperity, most of the sectors or industries experience an increase in output and during recession they experience a fall in output.

iv. Not all the industries are affected uniformly. Some are hit badly during depression while others are not affected seriously.

Investment goods industries fluctuate more than the consumer goods industries. Further, industries producing consumer durable goods generally experience greater fluctuations than sectors producing non-durable goods. Further, fluctuations in the service sector are highly insignificant in comparison with both capital goods and consumer goods industries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

v. One also observes the tendency for consumer goods output to lead investment goods output in the cycle. During recovery, increase in output of consumer goods usually precedes that of investment goods. Thus, the recovery of consumer goods industries from recessionary tendencies is quicker than those of investment goods industries.

vi. Just as outputs move together in the same direction, so do the prices of various goods and services, though prices lag behind output. Fluctuations in the prices of agricultural products are more marked than those of prices of manufactured articles.

vii. Profits tend to be highly variable and pro-cyclical. Usually, profits decline in recession and rise in boom. On the other hand, wages are more or less sticky though they tend to rise during boom.

viii. Trade cycles are ‘international’ in character in the sense that fluctuations in one country get transmitted to other countries. This is because, in this age of globalization, dependence of one country on other countries is great.

ix. Periodicity of a trade cycle is not uniform, though fluctuations are something in the range of five to ten years from peak to peak. Every cycle exhibits similarities in its nature and direction though no two cycles are exactly the same.

In the words of Samuelson: “No two business cycles are quite the same. Yet they have much in common. Though not identical twins, they are recognizable as belonging to the same family.”

x. Every cycle has four distinct phases:

(a) depression

(b) revival

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) prosperity or boom

(d) recession.

Phases of a Business Cycle:

A typical business cycle has two phases— expansion phase or upswing or peak; and contraction phase or downswing or trough. The upswing or expansion phase exhibits a more rapid growth of GNP than the long run trend growth rate. At some point, GNP reaches its upper turning point and the downswing of the cycle begins. In the contraction phase, GNP declines.

At some time, GNP reaches its lower turning point and expansion begins. Starting from a lower turning point, a cycle experiences the phase of recovery and after some time it reaches the upper turning point—the peak. But, continuous prosperity can never occur and the process of downhill starts. In this contraction phase, a cycle exhibits first a recession and then, finally, reaches the bottom—the depression.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, a trade cycle has four phases:

(i) Depression

(ii) Revival

(iii) Boom

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iv) Recession

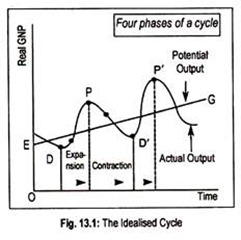

These phases of a trade cycle are illustrated in Fig. 13.1. In this figure, the secular growth path or trend growth rate of GNP has been labeled as EG.

Now we briefly describe the essential characteristics of these phases of an idealized cycle:

i. Depression or Trough:

The depression or trough is the bottom of a cycle where economic activity remains at a very low level. Income, employment, output, price level, etc., go down. A depression is generally characterized by high unemployment of labour and capital and a low level of consumer demand in relation to the economy’s capacity to produce.

This deficiency in demand forces firms to cut back production and lay-off workers. Thus, there develops a substantial amount of unused productive capacity in the economy. Even by lowering down the interest rates financial institutions do not find enough borrowers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Profits may even become negative. Firms become hesitant in making fresh investments. Thus, an air of pessimism engulfs the entire economy and the economy lands into the phase of depression. However, the seeds of recovery of the economy lie dormant in this phase.

ii. Recovery:

Since trough is not a permanent phenomenon, a capitalistic economy experiences expansion and, therefore, the process of recovery starts. During depression some machines wear out completely and, ultimately, become useless. For their survival, businessmen replace old and worn out machines.

Thus, spending spree starts, of course, hesitantly. This gives an optimistic signal to the economy. Industries begin to rise and expectations become more favourable. Pessimism that once prevailed in the economy now makes room for optimism. Investment becomes no longer risky.

Additional and fresh investments lead to a rise in production. Increased production leads to an increase in the demand for inputs. Employment of more labour and capital causes GNP to rise. Further, low interest rates charged by banks in the early years of recovery phase act as an incentive to producers to borrow money. Thus, investment rises.

Now plants get utilized in a better way. General Price level starts rising. The recovery phase, however, gets gradually cumulative and income, employment, profit, price, etc., start increasing. There occurs an interaction between multiplier and acceleration principle and the economy then climbs up to peak.

iii. Prosperity:

Once the forces of revival get strengthened the level of economic activity tends to reach the highest point—the peak. A peak is the top of a cycle. The peak is characterized by an all-round optimism in the economy—income, employment, output, and price level tend to rise.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Meanwhile, a rise in aggregate demand and cost leads to a rise in both investment and price level. But once the economy reaches the level of full employment, additional investment will not cause GNP to rise. On the other hand, demand, price level, and cost of production will rise.

During prosperity, existing capacity of plants is over-utilised. Labour and raw material shortages develop. Scarcity of resources leads to rising cost. Aggregate demand now outstrips aggregate supply. Businessmen now come to learn that they have overstepped the limit. High optimism now gives birth to pessimism. This, ultimately, slows down the economic expansion and paves the way for contraction.

iv. Recession:

Like depression, prosperity or peak can never be long-lasting. Actually speaking, the bubble of prosperity gradually dies down. During this phase, the demand of firms and households for goods and services start to fall. No new industries are set up. Sometimes, existing industries are wound up.

Unsold goods pile up because of low household demand. Profits of business firms dwindle. Output and employment levels are reduced. Eventually, this contracting economy hits the slump again. A recession that is deep and long-lasting is called a depression and, thus, the whole process restarts.

The four-phased trade cycle has the following attributes:

(i) Depression lasts longer than prosperity

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) The process of revival starts gradually

(iii) Prosperity phase is characterized by extreme activity in the business world

(iv) The phase of prosperity comes to an end abruptly.

The period of a cycle, i.e., the length of time required for the completion of one complete cycle, is measured from peak to peak (P to P’) and from trough to trough (from D to D’) The shortest of the cycle is called ‘seasonal’.

Theories of the Trade Cycle:

There are many possible causes of trade cycle. In other words, there may be different shocks or disturbances that hit the economy. It may happen that a single shock outside the system may generate cyclical fluctuations.

That is to say, exogenous variables or external shocks have the potentiality of generating cycles. Sometimes endogenous variables—i.e., internal shocks—generate cycles. Thus, we have two types of theories of trade cycles. These are external theories and internal theories.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Sometimes exogenous variables—i.e., the factors outside the economic system—explain the cyclical behaviour of an economy. For example, external factors like war, sunspots, revolution, discovery of gold mines, etc., generate cyclical fluctuations.

Earlier, economist W. S. Jevons ascribed fluctuations of an economy to sunspots that appear almost regularly in a span of 10 to 15 years. According to Schumpeter, innovation may result in cyclical fluctuations in a dynamic economy.

Internal or endogenous variables like national income, consumption, investment etc., generate continual ebb and flow of business activity. However, quite often the distinction between these two theories gets blurred in the actual working of an economic system.

Here we will present two important theories that attempt to explain cycles:

(i) Accelerator theory of investment

(ii) Multiplier-accelerator interaction.

The Acceleration Principle:

Keynes’ investment multiplier shows a relationship between a change in income (∆Y) and a change in autonomous investment (∆I). It shows that a change in investment gives rise to a change in national income greater than the increase in investment via the change in consumption spending.

We know that as autonomous investment rises, national income rises. Increased income leads to an increase in consumption spending. To meet this increased demand, output has to be increased by making additional investment. Such investment is called induced investment.

Thus, change in income leads to a change in investment. This is the essence of the acceleration principle. Keynes did not consider this induced investment spending. The acceleration principle shows the relationship between a change in income or consumption and a change in induced investment spending.

The accelerator theory of investment states that investment occurs to enlarge the stock of capital because more capital is required to produce more output. In other words, a particular amount of capital stock is necessary to produce a given output.

The relation between the capital stock and output is known as the capital-output ratio. If a capital stock of Rs. 400 crore is required to produce an output worth Rs. 100 crore then the capital-output ratio becomes 4: 1.

Let K be the capital stock, Y the level of output and ‘v’ the capital-output ratio that firm considers optimum. Then we have

K = vY …(13.1)

Equation (13.1) describes a simple proportional relationship between capital stock and output.

If v = 2, then K of Rs. 400 crore is desired for Y of Rs. 200 crore. Let us assume that v remains unchanged over time. However, the desired stock of capital will change when there occurs a change in output. Designating current period of time as t, the preceding period as t – 1 and the following period by t + 1, when income is Yt – 1 then the required capital stock becomes

Kt – 1 = vYt – 1 …(13.2)

If income or output rises from Yt – 1 to Yt, then the desired capital stock would rise from Kt – 1 to Kt. That is,

Kt = vYt …(13.3)

Thus, the increase in the stock of capital is Kt – Kt – 1. Increase in the stock of capital represents net investment, i.e.,

It = Kt – Kt – 1 …(13.4)

where It is the net investment at time t. Equation (13.4) can be written as

It = v Yt – vYt – 1

= v (Yt – Yt – 1) …(13.5)

Equation (13.5) says that net investment at time t depends on the change in output or income from t -1 to t times the capital-output ratio, v.

Though gross investment is always positive, net investment may be positive when Yt > Yt – 1 and negative when Yt < Yt – 1. Thus, net investment is positively related to changes in output. If gross investment is taken into account we should consider replacement investment or depreciation allowances.

The basic relationship between the change in income or output and investment is known as the acceleration principle. The capital- output ratio or V is the accelerator. The acceleration coefficient or the accelerator depends on the capital-output ratio and the stability of capital. If the accelerator becomes greater than one, then it implies that investment demand gets more magnified than the increase in income or output.

Investment demand becomes less responsive to a change in income when accelerator takes a value less than one. In a handicraft industry, the accelerator is usually found to be zero since, even if output in these industries rises, there occurs no change in net investment. However, the accelerator usually becomes greater than one.

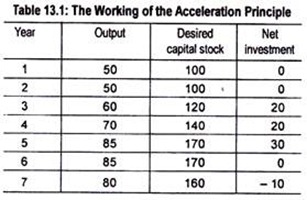

Arithmetical Example:

A simple example will explain the principle. To keep the example simple, let us assume that there is no depreciation. In other words, we consider gross investment. Let the capital- output ratio be 2. Let us now trace the changes in output and net investment over a number of time periods.

As output remains unchanged from period 1 to period 2, no net investment takes place. When output increases to 60 units in period 3, the desired capital stock will rise to 120 units and, to achieve this, net investment worth 20 is required. This is because, with an accelerator of 2, an increase in output of 10 units produces an increase in the demand for capital goods by 20.

In year 4, as output rises to 70, the desired capital stock rises to 140 and net investment grows by 20. In year 5, output has risen to 85 so that the desired capital stock grows to 170.

Consequently, net investment rises to 30. However, in the next year, since output remains stationary at 85, no new net investment is necessary. But in period 7, fall in output results in a decline in desired capital stock and net investment becomes negative.

A real-life example may be given here: With the growth in literacy and a drop in dropout rates, the number of students joining the primary school will rise at a rapid rate.

This will lead to an increase in the demand for teachers and more new schools. Once the number of primary students decline, the demand for such schools and teachers and other necessary infrastructures will decline— thereby causing a drop in investment in these areas.

Thus, the acceleration principle emphasizes the role of net investment that brings about fluctuations in national income. Desired capital stock and, hence, net investment, depends on the changes in output. In other words, net investment is sensitive to output changes. This phenomenon contributes to cyclical fluctuations.

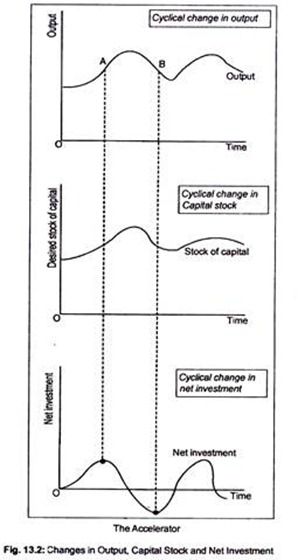

This is illustrated in Fig. 13.2. The upper part of Fig. 13.2 shows cyclical change in output, the middle part describes changes in capital stock while the bottom part exhibits cyclical change in net investment over time.

The output growth curve shows that at point A the slope of the curve is maximum while it is minimum at point B. Corresponding to the output growth curve, the stock of capital changes. Corresponding to point A, net investment is at peak.

However, net investment reaches trough (here negative) when the rate of growth of output is minimum (i.e., point B). Thus, this accelerator theory posits a mechanical and rigid response of net investment to changes in demand for consumer goods and, thus, aggregatively, to changes in output or national income.

However, this simple accelerator will come into operation provided certain assumptions are made. Firstly, the theory assumes no excess capacity. Secondly, there exists a fixed ratio between capital and output. In other words, it assumes fixed capital-output ratio. Thirdly, the theory assumes that a gap between desired and actual capital stock is eliminated within a single time period.

Under these assumptions, one can suggest that the economy is unstable; relatively ‘minor’ changes in the rate of growth of final sales and, hence, national income, will be translated into ‘large’ changes in net investment. “Thus, in the literature, the discussion of the accelerator has generally been included as a part of the analysis of economic disturbances and the business cycle.”

Criticisms:

Each assumption of the accelerator is questionable. Firstly, there shall be no excess capacity if accelerator is to work. Actually, there emerges excess capacity during recession. During this time, output may be expanded without adding to the amount of capital. Thus, the link between output changes and investment is broken.

Secondly, the capital-output ratio may not be constant when firms adjust their capital stock to each change in demand.

Thirdly, when the capital goods industries operate at full capacity it may not be possible to eliminate the discrepancy between the desired and actual capital stock in a single time period.

In view of these criticisms, modern economists explain cyclical fluctuations by conducting a marriage between the multiplier and the acceleration principles.

Interaction of Multiplier and Accelerator—Hicks’ Theory:

The theory linking fluctuations in national income to fluctuations in investment unites the accelerator theory with the Keynesian multiplier theory. The multiplier theory shows how a change in autonomous investment spending brings about a change in national income via a change in consumption spending.

How much national income will rise in response to an increase in autonomous investment depends on the value of MPC. On the other hand, the acceleration principle shows the relationship between net induced investment and the change in national income. The acceleration principle demonstrates how disturbances in the economy may be magnified by the investment sector.

But the acceleration principle cannot explain adequately the fluctuations in income. Modern authors like J. R. Hicks and P. A. Samuelson have shown that the interaction between the multiplier and the accelerator produces cyclical fluctuations.

The interaction model follows the following steps:

Suppose an autonomous investment takes place in an economy. Consequently, national income tends to rise. But, how much income will rise following this volume of autonomous investment depends on the multiplier. However, now consumption spending tends to rise in response to an increase in national income.

This rise in income leads to a rise in investment. This investment is called induced investment. This induced investment further produces a magnified effect on the national income and so on.

We can summarize the resultant effects of interaction of multiplier and accelerator:

∆l → K → ∆Y → v → ∆l → K → ∆Y……

Here ‘K’ denotes multiplier and V denotes the accelerator.

This is the essence of the interaction model. The multiplier-accelerator process can explain the cumulative tendencies of recessions and booms. Here we will present Hicksian interaction model.

Hicks’ real or non-monetary theory may be constructed in the following way. In Hicks’ model, autonomous investment takes place at a fairly constant rate over the long run. This leads to a rise in income and the economy reaches the long run equilibrium growth path. The ratio of income to autonomous investment depends on the value of the multiplier.

This makes for so- called induced investment which leads to an increase in income, thereby throwing the economy out of equilibrium. This may produce upturns and the economic growth may taper off leading to a cumulative contraction in the economy. In this way, the interaction model explains upturn and downturn of an economy.

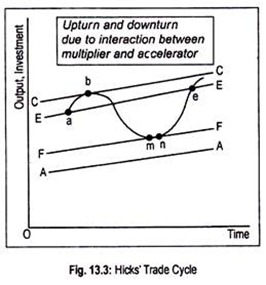

The Hicksian theory of cycle can be explained in terms of Fig. 13.3 where time is measured on the horizontal axis and output, investment, etc. are all measured on the vertical axis. The line AA shows autonomous investment and the line EE shows the equilibrium growth of income determined by the volume of autonomous investment.

The EE line remains a constant multiple of autonomous investment—the size of the multiplier depending on the values of the multiplier and the accelerator. The line CC represents the growth of full employment ceiling output.

The line FF is the lower limit or floor of contraction to which income can fall. Thus, CC and FF are the upper and lower boundaries within which fluctuations take place. In this figure, we have labelled these two limits by points a, b, m, n and e.

These points will now be described one by one:

i. Point ‘a’:

Point ‘a’ lies on the equilibrium path EE. This means that our economy is in equilibrium. Let us now suppose that an autonomous investment takes place. As a result, a cumulative upward movement occurs. A spurt in autonomous investment leads to a rise in income (the multiplier effect).

Rise in income again leads to a rise in induced investment (the acceleration principle) and income, consequently, tends to rise cumulatively. In this region, since both multiplier and accelerator come into action, cumulative expansion takes place.

ii. Point ‘b’:

‘B’ is the ceiling beyond which output cannot grow. Rather, it begins to move in a downward direction after crawling along the ceiling for a limited period. At ceiling output, autonomous investment becomes nil. The induced investment is too low to keep output at the highest level.

There develops an excess capacity. Consequently, accelerator becomes weak and the downward movement of output or income is inevitable. Expansion ends and contraction begins.

iii. Point ‘m’:

We know that as output falls there occurs disinvestment following negative accelerator. In other words, net induced investment is negative. The acceleration principle now becomes inoperative.

Here only the multiplier principle comes into operation.

But, at point ‘m’, the economy has reached the floor. As the accelerator becomes weaker during downswing there remains a floor of contraction. The economy experiences trough at point ‘m’.

iv. Point ‘n’:

Though autonomous investment declines during slump, it remains positive. That is why income grows along the floor. Hicks maintain that revival is inevitable since autonomous investment grows.

v. Point ‘e’:

The economy cannot move along the line FF since autonomous investment grows and, consequently, income grows. Once this income starts rising, a cumulative upward process is underway. Excess capacity gradually diminishes, induced net investment becomes positive and accelerator works efficiently.

“Via the interaction of the multiplier and accelerator, income overshoots the EE line and goes on up until finally restrained by the ceiling, the CC line, from which, as before, it bounces off and starts the downward movement of another cycle.”

Control of Trade Cycles:

There have been a large number of explanations of business fluctuations since different authors have different approaches. For instance, monetarists argue that business cycles have mainly monetary causes. According to monetarists, fluctuations in national income are caused by fluctuations in money supply. This explanation suggests a policy of stabilizing the growth in money supply.

In other words, monetarists rely on monetary policy as a countercyclical stabilization policy. Keynesians do not subscribe to this cause and remedy of business fluctuations. According to Keynesians, fluctuations in autonomous expenditures are the prime source of instability. To bring stability what is required is the fiscal policy devise as is suggested by Keynesians.

Thus, we have two sets of instruments that can offset instability in the economy.

These are monetary policy and fiscal policy in which the government acts as a stabilizer.

Monetary Policy (MP):

Money supply is under the control of the central bank. MP is a macroeconomic stabilization policy applied through changes in the money supply by the central bank. It is capable of influencing expansionary and contractionary forces on the economy.

In other words, the central bank can change the level of aggregate demand by altering the money supply through the tools of money supply control. Bank rate, open market operations, variable reserve ratio, selective credit controls are the principal monetary policy instruments. These instruments are employed by the central bank to affect the money supply.

During depression, the economy suffers from rising unemployment, falling price level, falling income and, above all, a shrinking economic activity. To relieve the economy from depression it is essential to increase the stock of money to step up aggregate demand. To this end, the central bank lowers down the bank rate as well as legal reserve requirement.

Further, the central bank may conduct open market purchases of securities so that borrowing and investment get stimulated. In addition to these quantitative methods of control, selective or qualitative methods of credit control are also applied by the central bank to step up investment and consumption during the depressionary phase of the cycle.

On the other hand, when resources of the country are fully employed and the economy is plagued with inflation, the appropriate MP remedy is the reduction in money supply. During the expansionary phase of the business cycle, the central bank raises bank rate and legal reserve requirement. It may also sell securities in the open market. Thus, during depression, a contractionary MP may be pursued by the central bank.

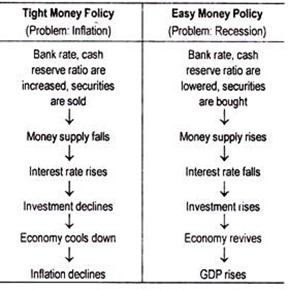

The following chart, in a nutshell, gives the essence of monetary policy:

Limitations:

However, MP has certain inherent limitations to stabilize the economy. Firstly, banks hold liquid assets in excess of the legal reserve requirements. These secondary reserves of the commercial banks tend to negate the action of the central bank. As a result, contractionary MP may fail to achieve the goal of reduction in money supply in the economy. Secondly, there is a timing problem of MP.

There may arise a considerable time lag between the emergence of the need for an expansionary (or contractionary) MP and the impact of policy implementation. Thirdly, the Keynesian liquidity trap reduces the efficacy of MP.

It is argued by Keynesians that the MP is ineffective in fighting depression. Our list of the limitations of MP is brief. Even then, economists contend that discretionary MP can significantly improve the economy’s performance rather than a steady growth of money supply at an annual rate of 4 to 5 p.c.

At the end, it must be said that (economic) globalization has reduced the effectiveness of macroeconomic policies. Globalization has resulted in an increased international financial flow between nations. If, for example, the central bank lowers bank rate and other interest rates to stimulate the economy, investors will be deterred to put their money in domestic economy and transfer their capital to other economies where interest rates are higher (lower).

As a result, the economy will shrink instead of getting stimulated. Opposite will come to stay if interest rates are increased by the central bank. That is why it is said that globalization tends to undermine the effectiveness of both fiscal and monetary policy.

Fiscal Policy (FP):

FP relates to taxation and expenditure programmes of the government. It also comprises borrowing and management of public debt. If it is to be employed as an instrument of macroeconomic stabilisation, it has to be contra-cyclical in behaviour. The government should orient its budget in such a way that revenue and expenditures are not balanced in the midst of fluctuating income and employment.

In other words, instead of a balanced budget, a surplus or a deficit budget should be pursued to achieve stability in the economy. Such deliberate changes in the tax rates and expenditure programme through the budget instrument is called the discretionary FP.

If the economy is caught in recession, the government shapes its budget policy in such a way that its expenditure exceeds income.

In order to contribute significantly to the levels of employment, income and economic activity, the government can take up a number of public works programmes, like road construction, irrigation, dam construction, slum clearance, etc. It can also provide unemployment allowance, poverty eradication measures, etc., so that incomes and consumption in the society rise in a multiplied form.

Similarly, to contain depressionary phase, tax cuts are recommended by the government so that disposable incomes rise. Again, repayment of debt is made to fight depression. Repayment of debt during the contractionary phase of the economy is likely to stimulate aggregate demand or spending.

This is what is required during recession. Keynes however, put less emphasis on changing tax rates than on government spending.

Reduction of aggregate spending is often recommended when the economy suffers from inflation. During this expansionary phase of the economy, government spending must fall short of its income. In other words, governmental expenditure programmes are to be curtailed to mop up excess purchasing power of the people.

Quite righty, tax rates are raised to control both consumption and investment. Such tax-expenditure programmes are simultaneously initiated to curb inflation or overheating of the economy. In addition, public borrowing is often suggested to combat expansionary phase of the cycle.

Limitations:

FP also suffers from certain limitations. Firstly, like MP, FP is also subject to time lags since government’s tax- expenditure programme requires prior approval of the legislature. Obviously, a long time is wasted between the emergence of the need for policy and the implementation. As a result, the restrictive policy may accelerate contraction—thereby destabilizing the economy.

Secondly, political compulsions may not permit the government to cut its public works programme during expansionary phase of the cycle. Further, the rise in tax rates during inflation may be counterproductive as far as win in election over the political rivals is concerned. Thirdly, it is argued that the government’s own fiscal actions are the major causes of economic instability.

How does a government act as a destabiliser is explained below:

When there is a mild recession with no significant inflation, unemployment is considered as the major problem. Then government pursues expansionary policy to fight unemployment problem. But now price level tends to rise and, ultimately, inflation becomes the number one economic problem. What is now pursued is the contractionary FP.

This reduces income but unemployment problem now reappears. Now the policy emphasis is on unemployment cure. However, with the shift to an expansionary FP in the midst of unemployment problem, a reacceleration of inflation is unavoidable. This phenomenon—popularly known as ‘stop-go’ policy—suggests that a government can act in a destabilizing way.

Though FP actions disrupt the economy, an endless boom-depression sequence is not allowed to grow. If fiscal stabilization programmes are applied judiciously they can smoothen the growth path of income.

This kind of FP as a corrective to recessions is called ‘loan expenditure’ by Keynes himself. The government takes loans and spends the money.

Milton Friedman—a noted critic of the fiscal stabilization policy—compares the government’s attempt to stabilize the economy to a “fool in the shower”.

As soon as the hot water tap switch is made ‘on’, the shower gives cold water first, because the warm water needs a little more time to flow. But the fool switches ‘on’, i.e., turns up the hot water. As it is yet to warm farther, the fool waits for the hot water to come out.

The hot water starts flowing but as it is too hot it scalds him. Feeling this kind of impact, he immediately turns up the cold water to have a soothing effect. If he does not get result, he will attempt to turn up the cold water further. When the cold water finally starts falling, he finds the shower too cold and so on. Thus, government policy to stabilize the economy can make matters worse.