The trade barriers other than import quotas include voluntary export restraints, technical, administrative and other regulations, trade restrictions due to international cartels, dumping and export subsidies. During the recent decades, many countries have started relying increasingly upon these forms of protectionism.

1. Voluntary Export Restraints (VER):

These restraints refer to a situation in which the importing country, faced with excessive competition from industries of the exporting country, threatens to put stiffer all round trade restrictions. That may induce the exporting country to-reduce the flow of exports voluntarily to the importing country.

The United States and other industrial countries have successfully negotiated with Japan since 1950’s to make the latter curtail its exports of textiles to them. During 1980’s again U.S.A. employed this method to make Japan and some other countries to reduce voluntarily their exports of automobiles, steel, shoes and certain agricultural commodities.

The voluntary export agreement sometimes covers more than one country. The most famous example of such an agreement is the Multi-Fiber Agreement (MFA) that restricted textile exports from 22 countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

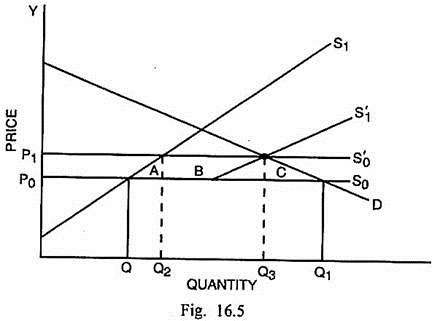

The effects of VER upon the importing country may be explained through Fig. 16.5.

In Fig. 16.5., D is the domestic demand curve and S1 is the domestic supply curve of good. Originally the world supply curve of the good at price OP0 is S0. The quantity imported is QQ1. If the exporting and importing countries enter the voluntary export agreement about the import of Q2Q3 quantity by the home country at the price OP1, the world supply curve shifts to S0’. The domestic supply curve shifts to S1‘.

The net loss to the importing home country is measured by the area (A + B + C). In case of tariffs, the area B represents the revenue gain to the government of the importing country. In case of equivalent VER, the equivalent amount is taken away by the foreign exporters in the form of rents. It is in fact this consideration of rent that makes the foreign suppliers to enter into the voluntary export arrangement.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The foreign suppliers enter into such an agreement because they can later supply high cost or luxury item to the importing country and increase their rent earnings. In addition, such an agreement allows them to have an opportunity of protected market for their products. There is also the fear that not making of such as an agreement will result in tariffs or other restrictions upon their exports.

The voluntary export restraints, if successful, will have exactly similar effects as are associated with import quotas. The only difference in that these are administered by the exporting country.

The voluntary export restraints are likely to be less effective for various reasons. Firstly, the exporting countries are very reluctant in agreeing to these restraints. Generally, such agreements involve protracted negotiations.

Secondly, the agreement may be binding upon a specific country. As exports are reduced by the given exporting country, the other countries may enter the market and enlarge their exports. It means there is no reduction in imports but only a replacement of imports from one country by those from the other.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thirdly, the country, forced to restrict the export of the commodity of a particular price and quality specification, may fill up its quota of market through products of upgraded quality specification and a higher level of price.

Fourthly, the exporting country, may continue to export through the third country trade.

Fifthly, this measure can be successfully employed by an economically powerful country like the U.S.A.

The less developed countries, faced with competition from the products of advanced countries, cannot force the latter to scale down their exports.

Sixthly, the VER result in the worsening of the terms of trade in the case of importing country because the domestic price of exporting country’s product is higher than the international price.

Seventhly, the VER discriminate against the low cost exporters. It is possible that imports are made from the higher cost exporters resulting in an increase in the bill of the importing country.

If the advanced countries resort to this measure against the exports of manufactured goods from the less developed countries, it can have ruinous effect upon their programme of industrialisation in particular and economic growth in general.

2. Technical, Administrative and Other Regulations:

Another non-tariff barrier to international trade is in the form of numerous technical, administrative and other regulations. Among these regulations are included the safety regulations for automobiles and several other categories of machines, health regulations related to production and packaging of edible products, patent and copyright provisions and labeling requirements showing origin and constant.

Some of these regulations are, undoubtedly, legitimate, while some are meant essentially for protecting domestic production against imports from abroad. For instance, French ban on advertisement of Scotch whisky, British restriction on the showing of foreign films on British T.V. are veiled devices for restricting imports.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Still another form of trade restriction is one, which has emanated from laws. For example, ‘Buy American’ Act passed in the U.S.A. in 1933 provided for procurements by the government agencies.

These procurement plans assure price advantage to the domestic suppliers. Many countries, including both the advanced and less developed countries, have their procurement programmes out of the domestic production. The Tokyo Round of GATT negotiations led to an agreement that countries would avoid such practices and allow the foreign suppliers also a fair chance. One more form of restrictions on trade is the tax rebates given to the exporters from such indirect taxes as sales tax, excise duty and value added taxes.

This practice is extensively followed by both less developed and the advanced countries to place their respective exporters in a relatively better position. The trade is also restricted by such measures as international commodity agreements, multiple exchange rates, government procurements, customs valuation and classification, stiff import licensing procedures, local content regulations etc.

All these measures are clearly intended to benefit the home country at the expense of the rest-of-the-world. No doubt, there is need for removing these trade barriers but much progress in this direction is not likely to take place in the near future. The advanced countries like the U.S.A. want to maintain the trade restrictions against the other countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As regards other countries, they are being pressurised to liberalise trade. Such an attitude is a major hindrance in the dismantling of the regime of technical, administrative and other regulations.

3. Trade Restrictions due to International Cartels:

An international cartel is an organization of suppliers of a commodity located in different countries that agrees to restrict output and export of the given commodity with the object of increasing or maximising profits. According to Kindelberger, “Cartels are business agreements to regulate price, division of markets or other aspects of enterprises.”

In the opinion of Haberler, the international cartel is an act of “uniting the producers in a given branch of industry, of as many countries as possible, into an organisation to exercise a single planned control over production and price and possibility to divide markets between the different producing countries.”

The most prominent example of international cartel is OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) which by restricting output and exports, could push up the price of crude oil by four times between 1973 and 1974. Another instance of international cartel is International Air Transport Association (IATA) which is a cartel of major international airlines. It meets annually to prescribe international air fares and policies.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The international cartels are likely to be successful, if they fulfill certain requirements. Firstly, there are only a few suppliers of the given commodity.

Secondly, the suppliers are amenable to discipline and uniform business conduct.

Thirdly, the product is produced on a large scale and not by the small or medium-sized firms.

Fourthly, the commodity is such for which no close substitutes are available.

There is greater scope for the formation of international cartels in such group of industries, as have the following characteristics:

(i) The industries are those which hold control over certain important materials or other raw materials and the supply of which can be easily brought under effective and strict control as petroleum, iron, aluminum, sulphur etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) International cartels can be organised among such industries whose products are patented as in the case of electrical and electronic industries, chemicals, drugs and pharmaceutical industries.

(iii) Cartels can exist among those groups of industries, which enjoy economies of large-scale production in an abundant measure.

Assumptions:

The operations of an international cartel related to regulation of price and output can be discussed under the following assumptions:

(i) Cartel is concerned with a specified product such as oil, gas, iron ore etc.

(ii) The suppliers of the given commodity are only a few and they export it to other countries of the world.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) The aim of cartel is to maximise profits.

(iv) The world demand of the commodity is known to the cartel.

(v) The world demand curve for the commodity is less elastic.

(vi) The marginal cost curve of the cartel is the lateral summation of the marginal cost curves of the member countries.

(vii) All the member countries follow the agreed price and output regulations.

(viii) There is absence of close substitutes of the specified commodity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ix) There is no entry or exit of suppliers.

Given the above assumptions, the price and output policy of the international cartel can be explained through Fig. 16.6.

In Fig. 16.16, the output or exports of cartel are measured along horizontal scale and price is measured along the vertical scale. D is the world demand curve for the given commodity, which is relatively less elastic. MC is the marginal cost curve of the cartel. It is determined by the lateral summation of the MC curves of the member countries.

MR is the marginal revenue curve corresponding to the world demand curve D. Under the conditions of perfect competition, the equilibrium is determined at E0 where demand and supply are equal. The equilibrium quantity produced and exported in the world is OQ0 and price is OP0 under the competitive conditions. The export earnings from the commodity in such a situation are OQ0 × OP0 = OQ0E0P0. If the individual countries form cartel, the monopoly firm emerges.

The equilibrium of the cartel gets determined at R where MR = MC. The equilibrium output or quantity exported gets reduced to OQ1 and price gets increased to OP1. The total earning from exports is OQ1S1P1 and the total amount of profits of the cartel is R1RS1P1. From the viewpoint of the member countries of the cartel amount of profit R1RS1P1 is likely to be greater than profits EE0P0 under the conditions of perfect competition, otherwise they would have not created the cartel.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So the cartel results in gain for the member countries. But there is likely to be the welfare loss for the rest of the world. Cartel reduces output or exports from OQ0 to OQ1 and raises the price of the commodity from OP0 to OP1. The consumer’s surplus under competition was CE0P0. After the formation of cartel, the consumer’s surplus gets reduced CS1P1.

The loss in consumer’s surplus for the rest of the world amounts to CE0P0 – CS1P1 = P1S1E0P0. Thus even though cartel raises the profits of individual member countries, yet the rest of the world suffers a substantial loss in welfare.

Arguments for International Cartels:

The organization of international cartels is supported on the following main grounds:

(i) The strong international cartels can make the importing countries to either remove or lower the tariffs. If that happens, the welfare of the international community is likely to be maximised.

(ii) The cartels eliminate cut-throat competition and price war. That can lead to supply of products at stable prices. Thus international cartels can ensure stability in international prices.

(iii) If international cartels exist, there is much economy in respect of wasteful spending on advertising and cross transportation.

(iv) International cartels ensure pooling of technological know-how. The specialised and highly standardised products can be manufactured at very low costs and made available to all the prospective importing countries.

(v) The international cartels promote international agreements and economic co-operation.

Arguments against International Cartels:

There is strong opinion against the formation of international cartels.

The main arguments against them are as below:

(i) The organisation of cartels throttles competition and results in the exploitation of consumers through high prices, scarcity of the commodity and sub-standard products.

(ii) The argument that international cartels pave the way for reduction in tariffs is not valid. This benefit has not actually materialised. In the words of Haberler, “….international cartels are not a suitable instrument for demolishing tariff walls within any measurable time. Many of the present international cartels owe their own existence to tariffs. They are, therefore, scarcely adopted for destroying tariffs.”

(iii) The participating firms, belonging to different countries, have to follow a uniform policy, which may not be consistent with the economic interests of at least some of the countries.

(iv) An international cartel is formed through a loose agreement. If a member country is not satisfied with production quota, division of market or other policies, it may decide to leave the cartel. That threatens the existence of cartel.

(v) The successful cartels, except in the case of OPEC, are not likely to be organised in the LDC’s dominated by agriculture and handicrafts, where production is distributed too extensively among small producers. Most of the international cartels are formed by the advanced industrialised countries and these have served as the instruments of exploitation of the LDC’s and restriction of the international trade.

(vi) Any one supplier of a given product may decide to remain outside the cartel and make unrestricted sales at the prices slightly below the price fixed by the cartel. Such a situation was faced by OPEC too, when the countries like Britain, Norway and Mexico decided to remain outside that organisation.

(vii) Cartels are inherently unstable as these are threatened by competition from non-members and internal wrangling among the members.

In view of their serious shortcomings and restrictive effects upon trade and growth, the international opinion, at least in theory, is against the formation of international cartels.

4. Export Subsidies:

An important non- tariff device to influence the international trade and especially to expand home country’s exports is the export subsidies. The export subsidies are direct cash payments or the grant of tax relief and subsidised loans to nation’s exporters or potential exporters and/or low interest loans to the foreign buyers for stimulating exports.

Although the international agreements do not approve of resort to export subsidies, yet both developed and poor countries have extensively employed this device either in an explicit or disguised form.

During the recent years, the issue of farm subsidies became a matter of confrontation between the United States, on the one hand, and the countries of European Union (EU) and Japan on the other, it has resulted in the collapse of W.T.O. negotiations held at Cancun in September 2003. The export subsidies on farm products are still a very contentions issue at Doha Round of W.T.O. negotiations.

In 1984-86, the average rates of subsidies on farm products in Japan, the EC and the U.S.A. were 64 percent, 49 percent and 35 percent respectively. In Japan, the highest rate of subsidy among the farm products was 96 percent in the case of wheat and the lowest rate was 16 percent in the case of poultry. In the EC, the highest and lowest rates of subsidy were 75 percent and 18 percent in case of sugar and eggs respectively.

In the United States, the highest and lowest rates of subsidy in that period were 76 percent and 7 percent in case of sugar and eggs respectively. The United States insisted that the EC and Japan should scale down subsidies on the farm products so that the United States products could have greater access to the foreign markets.

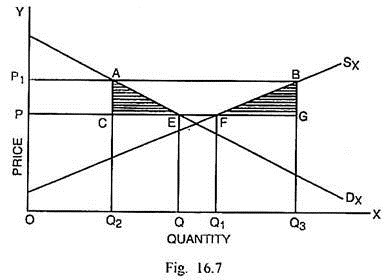

The effect of export subsidy or the cost of protection due to subsidies can be examined through Fig. 16.7. In this Fig., DX and SX are the demand and supply curve of the exportable commodity X of the home country A. The free trade world price of the commodity is OP.

At this price, the domestic supply is OQ1 and demand is OQ so that exportable surplus is QQ1. If PP1 per unit subsidy is extended, the price for domestic consumers and producers is OP1. At this price, the quantities demanded and supplied are respectively OQ2 and OQ3. The exportable surplus expands from QQ1 to Q2O3. The increase in domestic price results in a loss in consumer’s surplus by PEAP1. The gain in producer’s surplus, on the other hand, is PFBP1. The cost of subsidy is PP1 × Q2Q3 = AC × AB = ACGB

Net Loss or the Cost of Protection

= Loss in Consumer’s Surplus + Cost of Subsidy – Producer’s Surplus

= PEAP1 + ACGB – PFBP1

= ΔACE + ΔBGF

Thus the redistributive effects related to export subsidies can cause a net loss in welfare in the exporting country apart from the fact that the products of other countries will be at some disadvantage in foreign markets. As other countries also resort to counterveiling duties or export subsidies, there can be a serious restrictive effect upon the international trade.

5. Dumping:

The widespread impression about the term ‘dumping’ is the selling of the product in the foreign market below cost. But that is a wrong conception of dumping. Ellsworth and Leith defined dumping as “sales in a foreign market at a price below that received in the home market, after allowing for transportation charges, duties and all other costs of transfer.”

In the words of Haberler, “dumping is the sale of a good abroad at the price which is lower than the selling price of the same good at the same time and in the same circumstances (that is, under the same conditions of payments and so-on) at home, taking account of differences in transport costs.”

Thus the essential feature of dumping is price discrimination between the two markets. It is not necessary that the price discrimination or dumping occurs between the home market and foreign market. It may also take place between two regions in the home market or between two foreign markets.

Dumping has been classified into- (i) persistent, (ii) predatory and (iii) sporadic. The persistent dumping occurs when the domestic monopolist has a continuous policy to sell his product at a higher price in the domestic market than in the foreign market with the object of securing maximum profits. This kind of dumping can exist when the domestic demand for the product is inelastic but the foreign demand for the product is highly elastic. The predatory dumping is one in which a commodity is sold at below cost or at a lower price in the foreign market temporarily with the object of driving the rivals out of that market.

After the object is achieved, the prices are raised to take the benefit of newly acquired monopoly position in the foreign market. The sporadic dumping is the occasional sale of the commodity either at below cost or at a lower price in the foreign market than in the home market for the purpose of getting rid of unforeseen and temporary glut of inventory stocks that cannot be disposed of in the home market.

This kind of dumping can take place, if the demand for the product in the foreign market is more elastic than its demand in the home market.

The dumping can be successful or effective, if the following conditions exist:

(i) The producer should be a monopolist in the home market. If there are perfectly competitive conditions in the home market, the price will be equal to the average cost or marginal cost. In such a situation, the home producer cannot charge a lower price in the foreign market unless the government pays out subsidy to the home producers for making larger exports.

(ii) There should not be any possibility of the cheaper goods supplied in the foreign market flowing back to the home country. In order to prevent the flow back of the commodity, it is important that the difference between the foreign low price and domestic high price is less than the transport cost involved in the re-export of the commodity back to the country of origin.

Dumping is supposed to be beneficial from the point of view of the exporting country. It is believed that dumping makes the country get rid of unintended glut which, if disposed of in the home market, could have caused fall in prices and consequent slump in the system. If producer incurs any loss due to price difference, it can be easily compensated by the charging of high prices in the home market.

In the case of persistent dumping, the domestic price may be higher than before dumping only when the production is governed by the increasing costs. Such a possibility is unlikely to exist, if the production is governed by the law of constant cost or the law of decreasing costs. In the latter case (decreasing costs), it is possible that the producer changes a lower price in the long run even from the domestic buyers. In such a situation, there will be an increase in the level of welfare in the home country.

The persistent dumping is not likely to have adverse effect even upon the importing country because the goods are available at low prices continuously. But the effects of dumping on production in the importing country have to be assessed carefully. If dumping occurs in respect of consumer goods or producer goods, it may cause injury to industrial expansion. In case the exporting country has been dumping cheap raw material, the importing country may be able to establish some processing industries.

The persistent dumping is not likely to cause much harm to the economy of the importing country. It is often the sporadic dumping that causes injury to the latter. That is precisely the reason the importing countries feel the necessity of adopting counterveiling measures.

These measures include anti-dumping duties, which are equivalent to the difference between the selling prices in the exporting and the importing countries. In addition, the importing country may protect its industries from foreign dumping through the enforcement of import quotas.

Since the middle of 1970’s, the non-tariff barriers to trade have grown much more rapidly than the tariff barriers. At a time when WTO and other international economic institutions have been striving to reduce the tariff barriers, it is naturally a matter of great concern that almost half of the world trade is presently subject to non-tariff trade barriers.

In the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, the leading countries arrived at an agreement for dealing with the non-tariff trade barriers. However, any such trade arrangement, to succeed, must be fully consistent with the economic interests not only of the advanced countries but also of the less developed countries.